![]() The Sea Girl by Ray Cummings

The Sea Girl by Ray Cummings

A little while back, I had some words to say concerning Garrett P. Serviss’ truly excellent apocalyptic novel The Second Deluge, which was originally released in 1911. In that book, the Earth passes through a so-called “watery nebula,” and the resultant downpours cause the world’s oceans to rise over 30,000 feet, effectively inundating the entire planet! Well, now I am here to tell you about another Radium Age wonder, with precisely the opposite scenario. In Ray Cummings’ The Sea Girl, all the oceans on Earth mysteriously start to drop ever lower, until the point is reached where barely a drop remains, thus changing practically everything on our fair planet!

A little while back, I had some words to say concerning Garrett P. Serviss’ truly excellent apocalyptic novel The Second Deluge, which was originally released in 1911. In that book, the Earth passes through a so-called “watery nebula,” and the resultant downpours cause the world’s oceans to rise over 30,000 feet, effectively inundating the entire planet! Well, now I am here to tell you about another Radium Age wonder, with precisely the opposite scenario. In Ray Cummings’ The Sea Girl, all the oceans on Earth mysteriously start to drop ever lower, until the point is reached where barely a drop remains, thus changing practically everything on our fair planet!

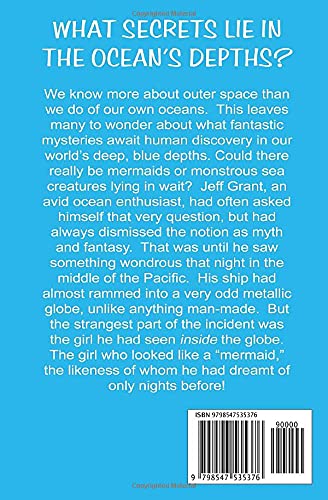

The Sea Girl, as was the case with Serviss’ book, was originally released as a six-part serial, but whereas The Second Deluge had initially appeared in the pages of the pulp magazine The Cavalier, Cummings’ first appeared in Argosy All-Story Weekly (which had merged with The Cavalier in 1914); specifically, the March 2 – April 6, 1929 issues, with the March 2nd issue sporting beautifully faithful cover art by Robert A. Graef. Again, similar to Serviss’ book, the novel would get the hardcover treatment the following year (a $2 affair from the American publisher A. C. McClurg & Co.), and, in 1932, another hardcover from the British house A. L. Burt & Co. And then, like so many of these pulp novels, the book would sadly go OOPs (out of prints) for a very long time – 89 years, in this case – until the fine folks at Armchair Fiction opted to rerelease it in fall 2021, and sporting the same Graef artwork that had graced its 3/2/29 premiere.

As for Cummings himself, he is an author whom I have long wanted to check out; a name that is practically unavoidable for fans of vintage sci-fi. Cummings was a New Yorker, like Serviss, but whereas Serviss had been born upstate in 1851, Cummings was born in 1887 in good ol’ NYC. And whereas Serviss had been, in addition to his fiction writing, a professional astronomer, Cummings was also no slouch in the realm of scientific matters, supposedly serving as an assistant to the great Thomas Alva Edison himself, from 1914 – 1919.

But starting around 1920, Cummings began producing sci-fi for the pulps at a prodigious rate, and by 1948, had come out with around 10 series, a dozen novels, and over 200 short stories. His most famous novel, 1922’s The Girl in the Golden Atom, is one that I hope to finally experience later this year. Cummings would ultimately pass away in 1957, at the age of 69. The Sea Girl, which came out toward the end of his first decade as a writer, is, once again, similar to The Second Deluge in that (if I may quote myself here) “It is a fairly thrilling book, generous with its sequences of cataclysmic spectacle and their aftermath…” And while Serviss’ novel is easily the more accomplished and better written of the two, The Sea Girl yet has much to offer.

Cummings’ book takes place in the futuristic years of, um, 1990 and 1991, and is narrated to us by then-22-year-old Jeff Grant, the second-in-command aboard a submarine freighter. While plying its trade in the Pacific, Grant’s ship receives a distress call from an old-fashioned surface freighter that promptly sinks, cause unknown. During the following weeks, many other surface vessels meet a similar fate, and this problematic state of affairs becomes even more dire when it is noticed that the planet’s tide levels have started to change. Eventually, the oceans begin to actually drop, losing over a fathom of depth every day. The sinkings of the world’s commerce vessels, and this even more serious loss of the oceans themselves, prompts Maine-based scientist Dr. Plantet to hasten the completion of his four-man submersible ship the Dolphin, which has been constructed to withstand pressures at a depth of 12,000 feet. And so, as the lowering of the ocean levels begins to cause both worldwide volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, Plantet, with Grant as his navigator, and spunky daughter Polly Plantet tagging along, has the Dolphin air-dropped in the Pacific, to try to ascertain the cause of these disasters. Meanwhile, Plantet’s son, Arturo, takes off for a barren Pacific atoll near the Marshall Islands, where a supposed “mermaid” had recently been sighted. Eventually, both missions prove successful, with Arturo meeting the so-called mermaid on that atoll – actually, a two-legged, 5-foot-tall maiden whom he dubs Nereid (the Graef cover fudges the true story a bit with its suggestion of a tail instead of two legs) – and Plantet & Co. observing the actions of a gaggle of undersea dwellers, with their scientific apparatus, off the coast of Maui.

Flash forward a year. The seas have stopped their subsidence, the maritime sinkings have ceased, and all seems well with the world, although Arturo has mysteriously disappeared with his Nereid. But suddenly, the oceans begin dropping at a rate even more drastic than before, and Grant begins receiving telepathic messages from Nereid, beseeching him to meet her and Arturo at the old atoll. Once the friends are reunited, Jeff is brought, via Nereid’s globe-shaped underwater craft, to the floor of the Pacific, and then, via a system of pits and locks, far below it, where he is vouchsafed the truth: Nereid’s people, the diminutive Middges, have long been subdued by another race of suboceanic dwellers, the Gians. The Gians are a gray-skinned, huge-statured race, whose Amazonian women are very much the absolute despotic rulers of their realm. And now, the Gian empress, Rhana, has decided to set her sights on a new conquest … the surface world itself! To accomplish this, after the work of generations, a system of floodgates leading to the floor of the Pacific has been constructed, and now, the waters of the Pacific itself are being allowed to drain into the bowels of the Earth; step 1 in Rhana’s plan of conquest. But what can Grant, Arturo, Nereid, and captured sailor Tad Megan possibly do to avert this impending worldwide catastrophe?

Flash forward a year. The seas have stopped their subsidence, the maritime sinkings have ceased, and all seems well with the world, although Arturo has mysteriously disappeared with his Nereid. But suddenly, the oceans begin dropping at a rate even more drastic than before, and Grant begins receiving telepathic messages from Nereid, beseeching him to meet her and Arturo at the old atoll. Once the friends are reunited, Jeff is brought, via Nereid’s globe-shaped underwater craft, to the floor of the Pacific, and then, via a system of pits and locks, far below it, where he is vouchsafed the truth: Nereid’s people, the diminutive Middges, have long been subdued by another race of suboceanic dwellers, the Gians. The Gians are a gray-skinned, huge-statured race, whose Amazonian women are very much the absolute despotic rulers of their realm. And now, the Gian empress, Rhana, has decided to set her sights on a new conquest … the surface world itself! To accomplish this, after the work of generations, a system of floodgates leading to the floor of the Pacific has been constructed, and now, the waters of the Pacific itself are being allowed to drain into the bowels of the Earth; step 1 in Rhana’s plan of conquest. But what can Grant, Arturo, Nereid, and captured sailor Tad Megan possibly do to avert this impending worldwide catastrophe?

Now, whereas Garrett P. Serviss’ novel is a fully realized, marvelously detailed and wholly satisfying epic, The Sea Girl strikes the reader as a book that could have been so much better. Cummings, at least in his novel here, writes in short, simply written sentences that often fail to supply the necessary details that his readers need to fully visualize his fantastic story line. Thus, your imaginative faculty may be required to go into overdrive here. (“Not that there’s anything wrong with that!”) Especially hard to picture – for this reader, anyway – was the suboceanic abyss of the Gians and Middges, being situated, as it is, on the ceiling of that immense suboceanic cavern; upside down, as it were! Similarly, Cummings’ descriptions of the monster-filled cavern leading to the floodgate system are also a bit nebulous and vague. An explanation of just how two such different races happened to evolve in the same area would have been illuminating, but sadly, Cummings never deigns to give us one. His novel is painted in very broad strokes, and is almost too fast moving in its breathlessly exciting final third. Indeed, one can’t help but feel that with a little more detail, stretched over perhaps a 10-part serial, the author might really have had something here; that his book might have wound up being a fully wonderful rediscovered classic, like Serviss’, instead of the entertaining page-turner that it remains today. And to be fair, there is a whole lot to enjoy in Cummings’ book as it is.

For one thing, the author gives his readers any number of well-handled sequences, including Arturo’s first run-in with Nereid on that barren atoll; the Dolphin’s altercation with the Gians off the coast of Maui; Jeff and Arturo’s imprisonment in Rhana’s castle, and their rescue therefrom; the traversing of the Abyss of the Monsters in a flying aerocar, vaguely delineated as it is; and, best of all, four back-to-back-to-back-to-back action scenes, featuring a battle with Rhana at the floodgates as they spectacularly collapse; the cataclysmic destruction of the suboceanic realm; the Middges’ lengthy climb up the miles-long tunnel to reach the (now-barren) Pacific Ocean bottom; and the final battle between Earth’s surface forces, the Middges and the Gians!

For those Radium Age readers who were big fans of exotic instances of superscience (probably all those readers!), Cummings offers up the Dolphin itself, as well as Nereid’s even more impressive globular craft; the Gians’ ray that acts much in the same manner as the tractor beam in the Star Trek universe; the use of long-range telepathy; the very notion of submarines being used as freighters; those flying aerocars; electromagnetically charged suits that render their wearers practically invisible; the personal force shield that Rhana wears as both protection and a murderous weapon; heat rays; and, unfortunately, the use of biological warfare (I suppose that Rhana had never been made familiar with the Geneva Convention!). Cummings’ book is also filled with all kinds of interesting touches, such as that 100-mile-wide fire cauldron near the Middges’ territory, the multileveled streets and public announcement screens that we get a look at in 1991’s NYC, and the whipping chains that Rhana is always shown wearing, attached to her wrists. Rhana, I might add, is a pretty colorful character, and it is thus a shame that more scenes could not have been added featuring her in them. Lustful, proud, wicked and completely without scruples, she makes for a very fine, if underused, villainess. Still, as I mentioned above, Cummings’ book grows relentlessly thrilling in its final third, and really might make for a spectacular sci-fi cinematic blockbuster one day … provided, of course, that the film’s producers invest the requisite $250 million to bring it faithfully to the screen. As it is, The Sea Girl will most likely leave most readers wishing that it had been followed up by a sequel, in which Cummings might have shown us what life on Earth had become, following the creation of a new “Lowlands” and the disappearance of all its oceans. His descriptions of the depleted seabeds, by the way, are often surprisingly effective and atmospheric. And as a writer, he is even capable of a lovely turn of phrase here and there, such as when he describes Nereid’s eyes for us:

…The sea was in her eyes, the changing sea, whipped with wind, dim with mist, wan with starlight … The mystery of the sea was in her eyes. Unfathomable green depths. Eyes that had seen things [Arturo] had never seen; things strange, unnatural to him…

Still, it would have been nice if Cummings hadn’t given us the occasional ungrammatical sentence, such as “Like an animal, caged, rushing one way and another and finding themselves surrounded by bars…” Or if he hadn’t confused the words “turbid” and “turgid” no fewer than seven times! In all, though, a valiant effort by Ray Cummings here, giving us a book that is wholly fun, but, as I said, should have been even better. And oh … I would advise all potential readers of The Sea Girl to have an atlas handy as they dive in; it will be helpful when the author starts dishing out the compass points of the novel’s many Pacific action sites.

And one thing more: This Armchair edition, thankfully, is mostly free of the many typographical and punctuational errors that have plagued so many of its previous editions. A good thing, too, as, after its disappearance from public availability for almost 90 years, The Sea Girl surely deserves as decent a presentation as it can possibly get! I look forward now to reading much more from Mr. Ray Cummings…

Your review had me googling “when were the Geneva Conventions adopted!”

Well, 1949. But still….