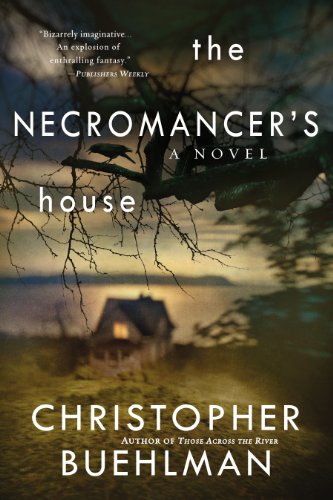

![]() The Necromancer’s House by Christopher Buehlman

The Necromancer’s House by Christopher Buehlman

The Necromancer’s House, by Christopher Buehlman, is a scary, funny, fast-paced urban fantasy novel with a rich voice and likeable characters. With its multiple viewpoints and several satisfying reveals along the way, it is one of the most well-crafted and exciting books I have read in a while.

Buehlman tells the story of Andrew Blankenship, a charming, brilliant modern wizard who drives an antique Mustang, wears his long black hair in a samurai bun, and goes to AA meetings regularly. He lives in the woods of upstate New York, in a house stocked and protected with ancient magic, much of it stolen from Baba Yaga in Soviet Russia. He’s in love with his lesbian apprentice, sleeps with a rusalka (a mermaid in Slavic myth), and is served and protected by the reanimated heart of his dead dog in the body of a wicker man. To put it simply, his life is not without complications at the beginning of the novel, but things are about to get a lot worse for Andrew.

After the rusalka drowns a Russian national, Baba Yaga is awakened to Andrew’s continued existence and vows to bring him down. She sends her daughter, along with other arcane magical forces, to hunt Blankenship and destroy him. At this point, it takes all of Andrew’s considerable magical knowledge, combined with that of several of his friends, to evade the arch-witch.

Buehlman has a background in both poetry and drama, and these influences make his writing shine. His dialogue is winding and funny, like the best plays, and some of his prose, laid out on the page in one-sentence paragraphs, reads like poetry. Descriptions like “an embarrassment of stars, like a fay court,” and “a tumble of scratches and playful bites and cheek-licking, a dance as old as man and dog and meat and fire” make the reading experience feel like a treasure hunt.

One of the most powerful tools in Andrew’s toolbox is his house — after all, the book is called The Necromancer’s House. He has armed it in several ways, forming layers of magical protection around himself. These are uniformly fascinating. It’s fun to watch Andrew change skins in his Room of Skins, although the consequences of leaving one’s human skin lying around are pretty bad if enemies get in. There is a tiny replica of the house in the attic with a dangerous surprise inside, a sleeping giant made of car parts in his front yard, and his bathroom appliances can be used to travel to other bathrooms (like in Harry Potter, not as in a flying toilet). In short, the house has so much personality, it’s basically a character in the book.

The other characters in The Necromancer’s House are just as interesting and well-developed. Even the ones we barely meet, like Radha, the computer mage from Chicago, have distinct voices and personalities. My favorite was Anneke, Andrew’s protégé and AA sponsee. She’s sharp and bad-ass and a little bit self-deceiving. Buehlman’s best description of her is as follows: “Anneke doesn’t do regret, or at least she tells herself that enough that it has become her mantra. If she were in Game of Thrones, her household words would be, ‘Yes, I did do that. And fuck you.’”

Andrew’s backstory is fully explored, including the tragic reasons for his alcoholism. Despite his arrogance and vanity — literally, one of the reasons he has left his defenses down for so long is that he uses magic to make himself young — I liked and empathized with him. I cried at the scene near the end of the book, when Andrew spends a last few moments with his reanimated dead dog, and then allows him to die — to go “outside” — for good.

The one era of his life left blank — intentionally — is his time in Soviet Russia as a prisoner of Baba Yaga. He relates this tale to a character in the book, but we do not get to hear it. Instead, Chapter 34 consists of one sentence: “He tells them what happened to him in Russia.” This narrative technique works much like Edgar Allan Poe’s negative description of the pit in his short story “The Pit and the Pendulum.” When we don’t know exactly what Baba Yaga is capable of, she could be capable of just about anything.

Full disclosure for you horror fans and/or –phobes: The Necromancer’s House, which is categorized by the publisher as “horror,” didn’t scare me. This is fine with me. I don’t usually like horror; I get too easily frightened and, unlike adrenaline junkies, don’t find it a pleasant experience. I couldn’t go to sleep the night that I watched Shyamalan’s The Village because I kept imagining the fake-monster-things looming next to my bed, and that’s horror-lite! (Terry, I imagine you are shaking your head at me right now. Pity me, for I am weak.)

The thing that really scares me is inhuman evil. Anything from Lovecraft, or Stephen King’s terrifying oil slick in “The Raft,” or even human killers who kill compulsively, with joy, instead of for “normal” reasons to murder someone (such as power, or revenge, or bad grammar). These are terrifying monsters to me, ideas that won’t let me sleep at night. Some of the creatures in this book would fit that category, but the main antagonist, Baba Yaga, seemed just as human as Andrew Blankenship. Despite the terror she unleashes (including several very inventive deaths), she wasn’t inexplicable to me. Or perhaps I just read too many illustrated books when I was a kid portraying her as a kindly old babushka with a neat house. Either way, I was happy that I was able to read Buehlman’s book without resorting to huddling beneath my comforter.

Hmm… I was reading a bit about Baba Yaga a few weeks ago, researching a short story. (I was looking at Russian folk tales, but there is no way to escape Baba Yaga if you’re doing that.)

I’m intrigued about what *she* would be doing during the Soviet Russian era. I think I will be ordering this book today, Kate!