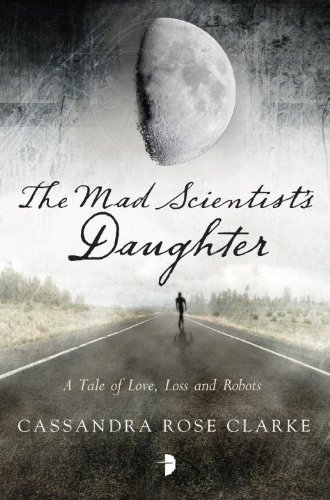

![]() The Mad Scientist’s Daughter by Cassandra Rose Clarke

The Mad Scientist’s Daughter by Cassandra Rose Clarke

“Cat, this is Finn. He’s going to be your tutor.”

The Mad Scientist’s Daughter by Cassandra Rose Clarke is a beautifully written story. Clarke evokes a beautiful contrast between the wild gardens and streams Cat inhabits as a child under the watchful eye of her tutor, and the cold, sterile, unfeeling world she inhabits as an adult in contact with other humans. At its core, this is a romance between a human and a cyborg. Though an interesting examination of what it means to be human, and the role of sentience in humanity, I felt that the role of sexual desire in defining humanity was overplayed in this book.

Clarke is especially skilled in describing a world that has suffered through an ecological disaster and is slowly rebuilding itself. The politics of humans versus robots as the economy and societies restabilize were less intense and violent than I thought likely to happen, when looking at the way America has dealt with immigration issues throughout its history. The beautiful descriptions of the climatic instability and both its long-term and short-term effects give this languorous tale an otherworldly effect.

I absolutely adored about the first 70% of the story. It was evocative and interesting and I thought Clarke did a great job in creating a believable world that doesn’t either glamorize or catastrophise the future unnecessarily. But I thought the last section of the book featured characters that had never really changed or matured, and an overly simplistic, and in my view disturbing, resolution to the problem of Finn and Cat’s relationship.

The rest of this review is spoilery, but is also key to understanding the strength of my negative response to the last section of the book. Continue reading at your own risk.

I think people who come to this book without my particular set of political convictions may be more of a fan of it than I was. At a certain point it became clear to me that as obsessed with declaring Finn to be real and deserving of rights as any other sentient being (i.e. humans), in actuality, Cat was as interested in possessing him for herself as the corporations were in owning him. Finn’s anger at having his programming changed, even for his own good, was downplayed — both by Cat and her father — and his leaving was also seen as unimaginable, an overreaction to the things going on in his life. And then, when Cat shows him that she can make him experience the physiological equivalent of an orgasm by pushing on his sensors in a specific pattern, he forgives her and they end up happily together, because apparently, sex fixes everything. She had fixed the last barrier to them being together, his inability to give her the full response she wanted.

This was particularly disturbing to me because I was trying to imagine the scenario written with the genders reversed. A brilliant scientist creates a female cyborg for his son, who then becomes obsessed with it and convinces himself that he is in love with this robot. He changes her programming, while swearing that she is a sentient being, to deepen the intensity of her response to him. He tries to understand her by reading her code instead of actually spending time with her. He keeps her isolated from all other beings, except when he shows her off like a toy, or wants her to be his date. He disregards the emotions that she has that are inconvenient for him, downplaying or dismissing them as an overreaction. He then, without her consent, causes her to have an orgasm.

That sounds like an abusive relationship to me, not a romance. And Cat, though we see her grow from a small child to a woman in her thirties, if not early forties, never really matures beyond the obsessive teenage love that she has when she and Finn first have sex. I kept waiting for something to happen to force her to grow up, but she keeps single-mindedly focused on this one idea as central to her identity. In that regard, she really is just the Mad Scientist’s Daughter, because she never becomes an adult of her own. In fact, I don’t think she really has an emotionally healthy adult relationship with anyone, human or non, in this entire book. The closest she comes to it is with her artist friends from college, but even there, they are providing her more with an emotional safe haven when she needs them, and they are dropped when she doesn’t. Cat is much more emotionally devoid of appropriate response than Finn.

I adore that cover.

You make a good point, Ruth. If the genders were reversed, we’d be disturbed by that relationship. Therefore it’s also wrong when it’s the other way around.

And I had to read the author name about three times before I realized it wasn’t Cassandra Clare, because she does a similarly disturbing dynamic in a short story of hers I’ve read, and it’s done on purpose and the character is supposed to be creepy.

I had the same problem with the author’s name, Kelly. I am kind of surprised that her agent didn’t make her change it. And I really thought a lot about whether or not she was trying to make it an intentional creepiness, but I don’t think that was the point. She’s not meant to be creepy. At least not that I could tell.

I bet the publisher likes the similarity. LOL!

From your review, it doesn’t sound like it was meant to be creepy — and even if it was, it’s a valid critique to say that the author didn’t get that across enough.

Ruth, this is a serious review but I did gurgle with laughter when I read, “… of orgasm by pushing on his sensors in a specific manner!” I think you have identified both a different standard of expectation, and the author’s failure to let the title character grow.

Yes, I had the same problem with the author’s name.