Gareth Hinds makes a lot of good decisions in his graphic version of Homer’s The Iliad (2019), both in terms of art and narration, resulting in a book that’s easy to recommend both to young adults and also educators/parents who want to slip a little classical knowledge into their kid’s comic book.

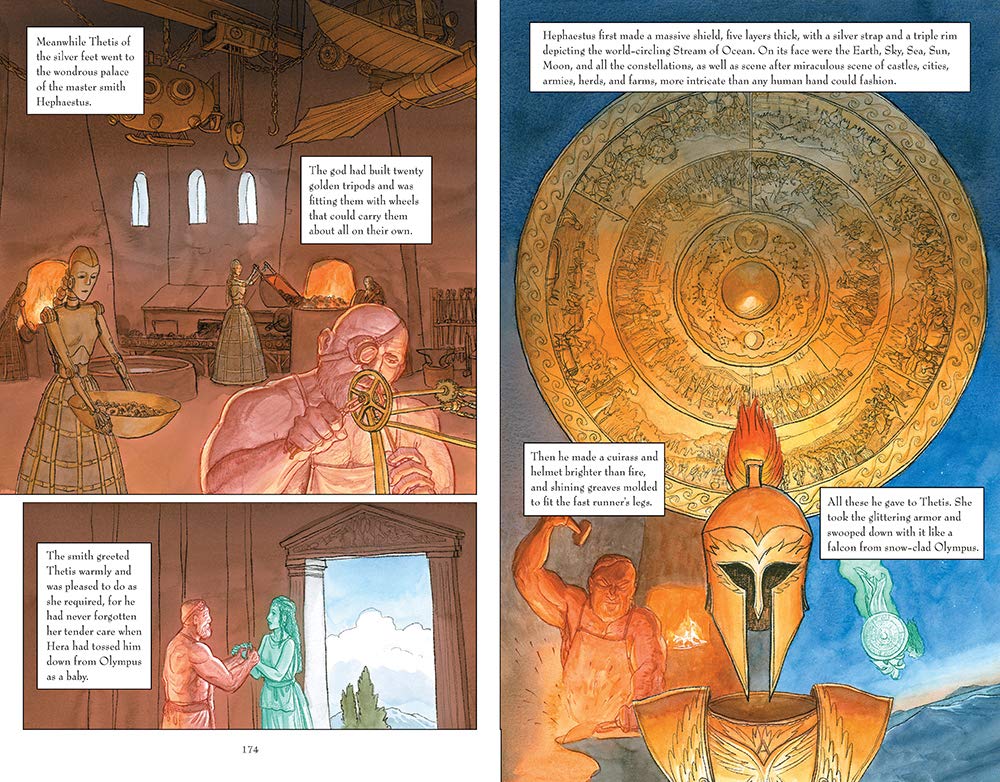

Two of those good decisions involve cleverly incorporating each major hero’s initial into their helm or breastplate and ignoring the historical reality, and portraying the two sides in uniform garb so as to more easily distinguish one from the other. Given the number of characters, and an avalanche of names, anything that helps to separate Greeks from Trojans and tell Achilles from Agamemnon is a boon to the reader. The art is clear and vivid throughout, working hand in hand with the text to clarify, expand, emphasize, and enhance. It’s all well done, but my favorite moments generally are the evening and night scenes, which he casts in a serene color palette that often matches the emotional tone of the scenes.

The story mostly moves along quickly thanks to Hinds’ choices of what to cut, which is a lot, but the core story is here, and he does fill other missing storylines in the addendums. Sometimes the list of deaths can slow things down, basically a catalog of names one after the other, but as Hinds nicely explains in the afterword, he’s simply emulating in abridged fashion Homer’s catalogs, which are there for a reason: that the deaths are given a face, a name, so we mourn a life and not just shrug at another faceless soldier (as the line goes, a thousand deaths is a statistic, a single death is a tragedy). The story, as with the original Iliad, does a nice job of capturing both the glorification of battle in a warrior culture and its butchery/horrific toll. Blood spurts, turns the river red, stains the soil.

Hinds’ prose style is clear and simple, with a solid rhythm in many places, and is at its best, I’d say, in the longer passages, which are often lyrical or weighted with emotion. As when he describes the truce to allow the sides to bury those killed that day: “With pails they washed the bloody filth away, and then hot tears fell as into waiting carts they lifted up their dead.” Or when he describes the Trojan camps encircling the Greeks: “There are nights when the upper air is windless, the sky so clear that every star shows bright in the firmament … As numerous as were the Trojan fires upon the plain — a thousand fires, with fifty men around each blaze and firelight glinting from their polished war-gear.”

Hinds bookmarks the major story with a prologue and some addendums (maps, character lists, a pantheon graphic, detailed notes on particular scenes) so as to provide some context as to what leads to the war and what follows after Homer’s closing scene (for instance, the Trojan Horse), as well as to flesh out the story a bit more by noting what he’s omitted in a given scene. He also offers up a bibliography noting the translations he used, as well as other resources.

Between Hinds’ work here and on The Odyssey, and George O’Connor’s series of books on the Greek gods, it’s a golden age of graphic retelling of classical Greek myths and both their works are highly recommended for young readers coming to them for the first time, older readers looking to refresh their memories, and parents, educators, and librarians. They’re pretty much must-haves for any home with children.

Do it! One of the best things I've read in recent years.

This reminds me. I want to read Addie LaRue.

We’re in total agreement David!

I felt just the same. The prose and character work was excellent. The larger story was unsatisfying, especially compared to…

Hmmm. I think I'll pass.