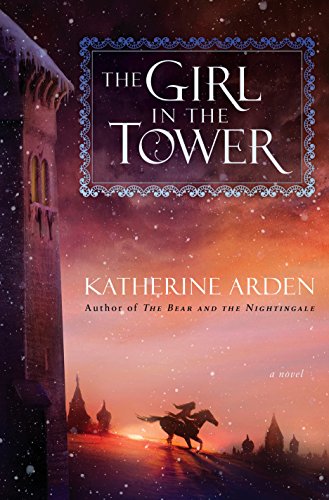

![]() The Girl in the Tower by Katherine Arden

The Girl in the Tower by Katherine Arden

The Girl in the Tower (2017), a medieval Russian fantasy, continues the story of Vasilisa (Vasya), a young woman whose story began in Katherine Arden’s debut novel The Bear and the Nightingale, one of my favorite fantasies from early 2017. That makes it a hard act to follow, but there’s no sophomore slump here. The Girl in the Tower is an even stronger novel, more sure-footed and compelling in its telling, and with more complex and nuanced characterization.

At the beginning of The Girl in the Tower, which picks up right where The Bear and the Nightingale ends, Vasya was leaving her childhood village of Lesnaya Zemlya in northern Rus’ to go to Moscow, where her sister Olga lives. Vasya’s life in Lesnaya Zemlya was threatened by villagers who view her as a witch. In a sense it’s true: Vasya has the rare ability to see and talk to the nature spirits and characters of Russian folklore, including the frost-demon Morozko, the Russian death-god. Morozko helps Vasya on her way as she travels toward Moscow alone, against all the norms for women and against Morozko’s advice, with only her stallion Solovey (the “Nightingale”) for company and protection.

The journey to Moscow is even more dangerous than usual. A mysterious group of bandits is making its way across the countryside, burning entire villages, slaughtering most of the villagers and kidnapping young girls for slavery. Vasya’s cousin Dmitrii Ivanovic, the current Grand Prince of Moscow, is out hunting for the bandits with the help of Vasya’s brother Sasha, a warrior-like priest. They’re unexpectedly joined by a red-haired lord called Kasyan Lutovich, who unexpectedly appears with his men to help with the search, explaining that his lands (called Bashnya Kostei, the “Tower of Bones”) have also been raided by these bandits.

Vasya’s refusal to comply with the customs and rules of 14th century Russia regarding the proper role and behavior of women ― in particular, highborn women ― gets Vasya into a lot of trouble, both on the way to Moscow and once she arrives. While Vasya is traveling alone through Russia, she dresses and acts as a young man for safety, hiding her long hair under a cap or hood. Once she runs into her cousin Dmitrii, she’s locked into that dangerous pretense. Dmitrii is charmed with the courageous young man that he thinks Vasya is, but Vasya ― not to mention Sasha, Olga and Olga’s family ― risk losing everything for carrying on with this deception. Meanwhile, there are also bandits to fight and Mongol conquerors to try to avoid paying heavy tribute to, and Vasya finds herself in the midst of that conflict.

Vasya is a spirited, fiercely independent young woman with no desire whatsoever to spend her life cooped up in a fine house with towers, as her sister Olga and young niece Marya do, or become a cloistered nun, which are the only options typically available to a highborn woman. It hurt my heart to see Vasya, in disguise as a boy, enjoying the freedoms men took for granted, knowing the terrible consequences discovery of her deception are likely to bring down upon her head. Olga, despite the restrictions on her life, is an intelligent woman who’s found a role in Moscow society that she’s reluctant to risk, not to mention her family’s status. Sasha, their brother, is another character who turns out to be more complex than he initially appears. The deeply conflicted priest Konstantin also reappears in The Girl in the Tower, but there’s far less of the “evils of Christianity” subtext that made The Bear and the Nightingale sometimes uncomfortable reading.

Katherine Arden weaves a magical tapestry of medieval Russia, but she doesn’t shy away from the harsh facts of life in those times. There’s a stark beauty to the land, its people and its folklore spirits, but the constraints on women are comparable to those on women in some of the stringent, restrictive cultures that still exist in our world today. Without dwelling overmuch on the point, Arden also makes you aware of the basic sanitary conditions and other aspects of day-to-day life in that age. Privileged princesses have rotten teeth; childbirth carries with it deadly dangers to mother and child.

The Girl in the Tower is entrancing: gorgeous and bleak and wonderful and terrifying, all at the same time. Arden immerses the reader in this vividly imagined world filled with both beauty and brutality. The WINTERNIGHT TRILOGY will conclude in The Winter of the Witch, due for publication in August 2018. I’ll be reading it as soon as I can possibly lay my hands on it!

![]() The Girl in the Tower is the second book in Katherine Arden’s ongoing series set in 14th-century Russia, following up on the events of The Bear and the Nightingale. While I found the first book to be a good read, I didn’t react quite as favorably as many other readers/critics did. The Girl in the Tower, however, won me over from the opening paragraph, kept me enraptured all the way through to its powerful close, and — thanks to some diabolically teasing lines — left me eager for the next installment.

The Girl in the Tower is the second book in Katherine Arden’s ongoing series set in 14th-century Russia, following up on the events of The Bear and the Nightingale. While I found the first book to be a good read, I didn’t react quite as favorably as many other readers/critics did. The Girl in the Tower, however, won me over from the opening paragraph, kept me enraptured all the way through to its powerful close, and — thanks to some diabolically teasing lines — left me eager for the next installment.

At the close of the first book (so yes, there will be some spoilers for that book here), Vasya had been forced from her home (partly due to outside forces, partly due to her own desire to escape her proscribed life and see the world). With some help from the frost-demon/Winter King/Death God Morozko and her smarter-than-your average-horse Solovey, Vasya barely survives the harsh Russian winter and an encounter with fearsome bandits who have been burning villages and abducting the young girls. Soon she ends up reunited with her brother Sasha, dashing warrior-monk and best friend/advisor to the Grand Prince Dmitri, who has left Moscow to hunt down the bandits at the behest of Kasyan, a mysterious hinterlands lord whose peasants have suffered great losses. Unfortunately, she meets them as a boy (her travel disguise), and is forced to play that role on their return trip to the big city, embroiling first her brother, and then her sister Olya (a princess in Moscow) in her dangerous lie.

I absolutely love what Arden has created with the character of Vasya. Her fiery, independent nature would make her likable enough, and many authors would have stopped there, with that independent streak breaking all the social boundaries of the time through sheer spunk. But Vasya’s independence is complicated by a realistically heavy dose of inexperience in terms of romance, social mores, and politics. And Arden makes for a richer, more bittersweet story with again, a more realistic portrayal of Vasya’s battle to be herself in a world dead set against any such thing: whether it be the prevailing attitude toward “witchery” or toward women and their place in society. Vasya is faced time and again with a choice-that-is-no-choice with regard to being herself or stifling her true nature, and while the modern reader is naturally predisposed to root for the “wild and free” Vasya, the choices are never so clear-cut, and the consequences are grave and heart-breaking. And in Olga, Vasya’s sister, Arden presents us a woman who has adhered to society’s strictures, but who is also strong in her own right.

I also like the way that Vasya’s situation — caught between being a child and being a young woman, caught between innocence and desire, caught between staying and leaving — is mirrored by other characters and by the larger setting. Dimitri, as Great Prince, is on the cusp himself of young adulthood and adulthood and is caught between his desire to avoid a destructive war and forge a national identity for his people. Sasha is caught between his own two sides: dashing warrior and trusted political advisor and more introspective/reflective priest, as well has between his love for his sister and his social upbringing. Russia is on the cusp of nationhood and being a vassal state to the Tatars. And the country’s religious background is on the cusp of Christian dominance, with the old gods/spirits fading away into the background literally and figuratively, but not entirely disappearing (Christianity, in Russia as elsewhere, may have become the dominant religion, but reports of the older beliefs’ demise were often greatly exaggerated).

The Slavic background is a nice change of pace from the same old same old, both in terms of geographic setting and its folkloric background (fans of Stravinsky’s Firebird — the ballet or suite — might find themselves humming the music in various segments). Both worlds come fully alive even in such a brief novel, with economical asides about the state of a character’s teeth, the construction of a hut, or the mode of travel in winter. Economy of language, though, doesn’t translate into pedestrian prose, with the descriptive passages especially lyrical, as with this early paragraph:

Moscow, just past midwinter, and the haze of ten thousand fires rose to meet a smothering sky. To the west a little light lingered, but in the east the clouds mounded up, bruise-colored in the livid dusk, buckling with unfallen snow. … [Moscow’s] squat white walls enclosed a jumble of hovels and churches, her palaces’ ice-streaked towers splayed like desperate fingers against the sky.

I had only a few small quibbles with The Girl in the Tower. The romance sometimes tiptoed the edge of melodrama, though I’d say Arden successfully pulls back each time and overall the romance plot is wonderfully handled. And a few things are a bit telegraphed and perhaps should have been more readily seen by the characters. But as noted, these were minor quibbles. The Girl in the Tower was overall a wonderfully engrossing read, and I’ve already checked out the release date for book three (August 2018 is too far in the future for my liking).

~Bill Capossere

Gotta get my mitts on this ASAP. :D Thanks, Tadiana!

Absolutely! Put it at the top of your list. ;)

I always feel immensely gratified when Bill agrees with my opinion of a book. ;)

Looks down, makes small circle in gravel with toe, blushes . . .

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!…