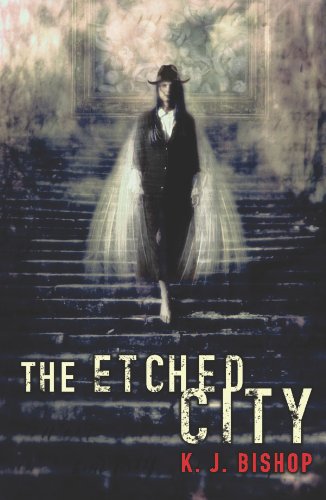

The Etched City by K.J. Bishop

The Etched City by K.J. Bishop

The Etched City is a story about a deteriorating tropical city whose denizens include the monstrous, the deranged, and the metamorphic, circling each other in rainy alleys and hot cafes. It’s been lauded as an intelligent and alluring novel. Bishop has been compared flatteringly with Miéville and Moorcock. While The Etched City certainly has plenty of brains and courage, it may be missing its heart.

The book opens on the dusty fringes of civilization, in a desolate Western landscape distantly reminiscent of King’s DARK TOWER books. Gwynn and Raule, our not-heroes, were both on the losing side of a recent civil war, which has left them aimless and morally apathetic. For the first fifty pages, they wander together through the desert, and the harsh climate lends a terse clarity to Bishop’s writing. But then they leave the desert. They settle in Ashamoil, a decadent, corrupt city in the heart of the tropics.

And there the story sits, rotting in the heat. Gwynn follows his amoral nature and works as a guard for a man who is a cross between the Godfather and a 17th century slave-trader. Raule follows her nobler nature, and works as a doctor in a poor district. Their paths rarely cross, and Gwynn’s colorful, violent life quickly steals the limelight. We watch him debate theology with the faithless Reverend, casually kill and maim for his employer, and fall in love with an enigmatic artist named Beth. Ashamoil and its inhabitants slowly deteriorate into madness, lust, violence, and delirium. The plot oozes languidly towards something like a climax, or a nadir, and the book ends in a sense of uncertain, faint hope.

The Etched City has brains by the bucketful. Bishop is writing in the nebulous New Weird, a genre that seems to require a vividly-imagined city, an absence of admirable characters, and the use of the word “gunslinger.” There’s also something self-consciously erudite about it. At its best, the pretension of the New Weird results in moments of lyrical insight and social criticism. Speaking of the absence of soul in the modern world, Beth declaims,

We are making an inert world; we are building a cemetery. And on the tombs, to remind us of life, we lay wreaths of poetry and bouquets of painting.

At its worst, The Etched City can feel like the stilted, rehearsed musings of a young philosophy major at his first party.

Courage, too, is perhaps intrinsic in the genre. Bishop steps well outside the bounds of fantasy, stitching together her own world from scraps of magical realism and half-remembered pieces of history. Her characters are also complicated, often opaque, and morally suspect. It takes a certain amount of courage to write a fantasy novel without a true hero, a true villain, or a true quest. But the bravest part of The Etched City is its subtle, disturbing treatment of magic.

Magic is the best and worst of fantasy. It can transcend the rigidity of the world and take us into the secret places behind it. Or, it can gloss lightly over the world’s harsh realities, obscuring meaning and depth with the wave of a sparkly plastic wand. Bishop’s magic is in the first category. Ashamoil is a secular city filled with hallucinogens but no real magic. But, subtly interwoven with nightmares and drug dreams, true magic seeps into the city. In one of my favorite moments, the Reverend drunkenly reveals his own strange magic:

…he grew cocoons on the palms of his hands. He never knew what would hatch when he did this. Often it was wasps; but he had also produced centipedes, scarab beetles, and even hummingbirds. This time, when the cocoons split, it was large luna moths that emerged onto his palms, where they sat fluttering their diaphanous pale green wings. When their wings were dry they flew away and up, climbing quickly through the air. The Rev watched them. Although he didn’t want to like them, he couldn’t help but think how beautiful they were. However, they were doomed.

If you are patient, and secretly rather attracted to young philosophy majors anyway, then The Etched City is worth reading solely for these luminous moments.

And yet, the book lacks a heart. My enthusiasm for it has mostly come to me after the fact, in thinking about Bishop’s inventiveness and ambition. The read itself lacks that certain power of compulsion that is one of the reasons I read fantasy. It’s hard to identify why, though: there’s enough violent suspense, enough introspection, enough tangled politicking, and enough delicate world-building to satisfy any reader. Perhaps it’s simply the sense that Bishop leaves you no one to love and nothing to believe in. I certainly didn’t love Gwynn (there’s a brief moment when he is presumed dead, and I moved through the seven stages of grief so quickly I was almost disappointed to see him revive). And I certainly wasn’t left with any swelling emotions or new worlds. Ashamoil is simply too lethargic, and too degenerate, to move me.

I remember loving the language and the imagery. I thought Gwynn was supposed to die at the end. The author became so besotted with him that the ending was changed, and weakened the book.

Great review! I totally know what to expect from this.