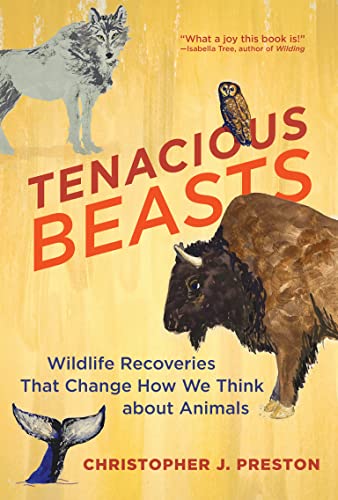

![]() Tenacious Beasts by Christopher J. Preston

Tenacious Beasts by Christopher J. Preston

Tenacious Beasts (2023) by Christopher J. Preston, is a rarity among environmental/ecological books nowadays — an uplifting work that highlights positivity, resilience, and hope for the future. As such, it’s a highly rewarding book and a breath of fresh air amongst all the depressing numbers out there having to do with our world and the creatures we share it with.

Tenacious Beasts (2023) by Christopher J. Preston, is a rarity among environmental/ecological books nowadays — an uplifting work that highlights positivity, resilience, and hope for the future. As such, it’s a highly rewarding book and a breath of fresh air amongst all the depressing numbers out there having to do with our world and the creatures we share it with.

That isn’t to say Preston turns a blind eye to those depressing numbers. Far from it. In fact, he begins by listing some of those very numbers:

Wildlife populations have declined 20 percent over the last century. More than nine hundred species have been wiped off the face of the earth since industrialization. At least a million are threatened with extinction … The collapse is almost certain to get worse … Ninety-six percent of the weight of the world’s mammalian life is either human or domestic animals.

He’s crystal clear regarding humanity’s catastrophic impact and quite keen early on and throughout to emphasize that “highlighting the recoveries is not to question the established wisdom about species loss.” But plenty of books exist to emphasize that loss, while this one’s intent is instead to highlight the (possible, tentative, cross-one’s-fingers-and-hope) recoveries of several species that we’ve managed to (maybe, perhaps, please-oh-please) pull back from extinction’s edge: the American bison, the beaver, the sea otter, the whale, and others. Preston makes this his focus not to muddy the issue of the ecological damage humans have caused but to point to a new way of viewing our relationship to animals, one that “challenge[s] entrenched ways of thinking and shake[s]us from well-worn habits of mind” so that “things might be different this time.”

Each chapter mostly focuses on a single species (with brief digressions to consider other animals, as well as on occasion plants and insects), setting the context for just how endangered they were, describing their current status, explaining how they got from one stage to the other, and then looking at what the future may hold. In addition to focusing on the animals, each section also raises a sort of essential question, a change in mind or habit that is required for these creatures to first survive, then thrive side-by-side with humanity.

To learns about the animals and the methods that have managed to bring them back from the brink of extinction, Preston travels around America and overseas, interviews a number of people (scientists and non-scientists), and gets his hands dirty more times than not, as when, for instance, he helps get semen out of a salmon.

He begins with a chapter on wolves. While Americans are probably aware of the successful rewilding of wolves in Yellowstone, while this success story crops up, Preston here is much more focused on the wolves’ resurgence in Europe and particularly their very recent [re] entry into the Netherlands. One of the pleasures in this book is its wider world view, not just with regard to the geography of the animals but also in how it examines the cultural differences that affect rewilding efforts. Geographically, for instance, much of Europe simply lacks the wide-open spaces of America’s western states; there is no Yellowstone to let wolves run free in, seen only by the occasionally lucky hiker or tourist with a spotting scope. Instead, European wolves by simple physical necessity prowl human spaces, trotting along vineyard rows or through olive groves. As well, because wolves are expanding on their own into countries, they are not “tainted” with the idea of being “forced” upon an unwilling populace by the government, something that has exacerbated conflict over the reintroduction of wolves into the Rockies (though Preston makes clear lots of farmers and livestock owners in Europe share the concerns of their American versions).

Later, in a chapter on attempts to reintroduce (or actually introduce — the genetic history is complicated) the steppe bison to England, Preston explores how the British have been completely cut off from any exposure to large animals, unlike Americans, who have lived near (or are at least able to travel to see) bear, mountain lions, bison, etc. England, on the other hand, is “one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world … in the bottom 10 percent of countries for the animals and plants is has left”, and all of those relatively small.

Preston doesn’t only highlight differences across countries or geographic regions, though. He also spotlights differing attitudes towards animals and nature between Native Americans and non-Native-Americans in the US, particularly in discussions of the resurgence of the American bison, salmon, and whales. The bison story is a well-trod one, but the connection of the bison — of today’s bison — to Native Americans is a tale told far less often, with most explorations of the subject only bringing in the Native Americans as a historical artifact side by side with the sweeping herds of 19th Century bison. The same holds true for Preston’s look at dam removal as a means of revitalizing salmon runs and Native American hunting/collecting methods as a means of a more sustainable and healthy ecologic system encompassing whales, otters, shellfish, and kelp (somewhat similarly, it was a pleasure to see how many female scientists/researchers are heard from).

Even in the sections that deal with more familiar stories, such as the slaughter of the bison and whale, Preston finds a way to bring something new and surprising into the mix. With the bison, along with centering the Native American connection to the species’ rejuvenation, there’s the idea of bringing them to England (a country I’m guessing most readers do not associate with bison), as well as the fascinating question of just how much genetic purity matters when one is discussing the revitalization of a species (just what percentage of cattle genes prevents us from calling a bison a bison if they look the same and perform the same ecological niche role?). With the whale and sea otter segments, the surprise (for me at least) came when Preston brought in a connection to climate change, not in the expected fashion of it being bad for animals, but in how both species can contribute to a sort of biological carbon capture system, thus helping reduce increasing greenhouse gases.

Preston is an engaging tour guide through the world of species recovery, offering a nicely non-American-centric point of view, a conversational tone with occasional lyrical flights, a host of fascinating details, and a number of stimulating and deeply thoughtful questions about how we can change in the way we talk and think of our relationships to the animal world. Though clear-eyed about the realities of our destructive nature and the appalling toll that nature has taken on the creatures we share the planet with, Tenacious Beasts gifts us with a few positive stories amidst the tragedy and carnage, and offers up a glimmer or two of hope if we can only heed the lessons those stories are trying to tell us. Highly recommended.

Do it! One of the best things I've read in recent years.

This reminds me. I want to read Addie LaRue.

We’re in total agreement David!

I felt just the same. The prose and character work was excellent. The larger story was unsatisfying, especially compared to…

Hmmm. I think I'll pass.