For many people, the mention of Japanese horror cinema will most likely bring to mind the series of colorful monster movies that Toho Studios brought to the world, starting with 1954’s Gojira. But while those Godzilla, Mothra, Rodan, King Kong and assorted kaiju-eiga films were undoubtedly a lot of fun, as any horror fan would tell you, they are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the field of Japanese horror, or J-horror as it is known today. From the increasingly sophisticated horror fare of the 1960s to the unbelievably gore-drenched and pyrotechnic displays of the late ‘90s and 2000s, the world of the Japanese horror picture has expanded into realms that will assuredly leave most viewers slack jawed and dumbfounded. I have already written here of such mindblowers as Goke, Body Snatcher From Hell; Suicide Club; Tokyo Gore Police; and Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Girl, and in today’s Shocktober column would like to shine a light on a half dozen other exemplars of J-horror that have impressed me in the past. Each one of these will assuredly make for perfect fare during this spookiest of holiday seasons:

The seismic, tsunamic and nuclear events that transpired in Japan in March 2011 have served to demonstrate quite dramatically that sometimes, life on Earth can be a living hell. For a glimpse at a more traditional Japanese vision of Hades, though, one need look no further than Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1960 film Jigoku (or “Hell”), a picture whose reputation seems to be on the rise lately, thanks in part to the great-looking Criterion DVD that I recently experienced. I had only seen one of Nakagawa’s 96 other films before taking in Jigoku, and that was 1968’s Snake Woman’s Curse, a well-done if lighthearted tale of ghostly vengeance told in the EC Comics manner. Jigoku is a whole different kettle of fugu, and easily the more impressive picture. In it, we meet a young student named Shiro, played by the handsome and very likable Shigeru Amachi. Newly engaged, his life takes a decisive turn when he is involved in a hit-and-run accident one night, and is unable to convince his demonic acquaintance, Tamura (Yoichi Numata) – the actual driver of the car – to report the incident. Before long, every person in Shiro’s life begins to meet an early demise, in advance of the journey to the realm down under (and no, I don’t mean Australia!). Jigoku, though over 60 years old now, feels surprisingly modern, with great use of color and a strong emphasis on jazz, drugs and femme fatales. The film’s first 1/3, the Tokyo segment, could almost be a Japanese noir, with its yakuza and nightclub elements. The central section slows down a bit, as Shiro goes to his parents’ old-age home in the country. But even during this slow stretch, Nakagawa manages to hold our interest with some surprising bursts of violence and the utilization of moody lighting and bizarre camera angles. The film’s final 1/3, however, is something else again, when virtually every character in the film is judged and suffers all the myriad torments and tortures in hell. In this segment, the patient horror buff is treated to numerous fire pits, skewerings, a severing of hands, flayings, eye gouging, the shattering of teeth, a lake of blood, cesspool fountains, a vortex of massed sufferers and on and on; truly, a hellacious environment, made even more memorable via the film’s use of expressionistic sets. Do all the film’s characters deserve such a horrible end? Hell, no! Shiro’s only sin seems to be that he is a victim of fateful happenstance, and his fiancée’s, some mere premarital sex. Enma, the so-called King of Hell here, can be SO strict! Regardless, this is some pretty impressive work. From its opening dirge regarding the briefness of man’s stay on Earth to its closing image of “lotus blossom purification,” Jigoku is a film that should keep all potential sinners on the straight and narrow…

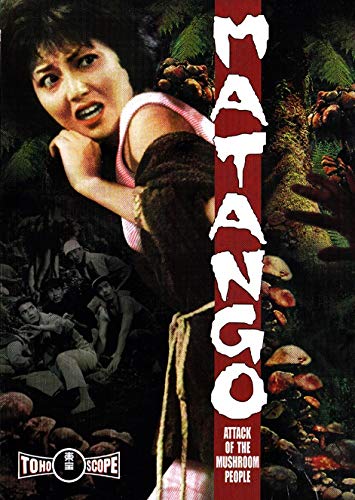

![]() MATANGO: ATTACK OF THE MUSHROOM PEOPLE (1963)

MATANGO: ATTACK OF THE MUSHROOM PEOPLE (1963)

(I couldn’t resist … here’s a seldom-discussed film from the aforementioned Toho Studios.) And you thought that YOU ate some funny mushrooms back in your college days! Just take a look at the ‘shrooms that the seven island castaways in the 1963 Japanese horror outing Matango: Attack of the Mushroom People partake in! In this film, directed by Toho Studios great Ishiro Honda, the seven people in question go on a yacht outing, get trapped in a storm and are washed ashore on a desert isle. The seven – the skipper, his first mate, a beautiful TV star, another pretty girl, a millionaire (hey, wait a minute … could Gilligan’s Island, which premiered the following year, have stolen from THIS film of all films?!?!), a writer and a psychiatrist – feed on the funny fungi and are soon turned into walking shiitakes themselves. Actually, despite the outrageous title and bizarre plot, this is a fairly levelheaded, reasonably intelligent and restrained film, not the laughable piece of crap you might be expecting. The picture is very well shot, and appears just fine on this pristine-looking, wide-screen DVD. The first half is a bit slow but nonetheless suspenseful, as the characters explore the perpetually fog-enshrouded island, and the second half, in which the fungus folk get it on, is occasionally quite trippy and hallucinatory. Remarkably, the DVD that I recently watched also features loads of interesting extras, including interviews with some of the folks behind the cameras and some fun trailers for other Toho Studios pictures. All in all, this film is certainly worth a rental … especially so that you can tell your coworkers that you saw a movie last night called Matango: Attack of the Mushroom People!

(I couldn’t resist … here’s a seldom-discussed film from the aforementioned Toho Studios.) And you thought that YOU ate some funny mushrooms back in your college days! Just take a look at the ‘shrooms that the seven island castaways in the 1963 Japanese horror outing Matango: Attack of the Mushroom People partake in! In this film, directed by Toho Studios great Ishiro Honda, the seven people in question go on a yacht outing, get trapped in a storm and are washed ashore on a desert isle. The seven – the skipper, his first mate, a beautiful TV star, another pretty girl, a millionaire (hey, wait a minute … could Gilligan’s Island, which premiered the following year, have stolen from THIS film of all films?!?!), a writer and a psychiatrist – feed on the funny fungi and are soon turned into walking shiitakes themselves. Actually, despite the outrageous title and bizarre plot, this is a fairly levelheaded, reasonably intelligent and restrained film, not the laughable piece of crap you might be expecting. The picture is very well shot, and appears just fine on this pristine-looking, wide-screen DVD. The first half is a bit slow but nonetheless suspenseful, as the characters explore the perpetually fog-enshrouded island, and the second half, in which the fungus folk get it on, is occasionally quite trippy and hallucinatory. Remarkably, the DVD that I recently watched also features loads of interesting extras, including interviews with some of the folks behind the cameras and some fun trailers for other Toho Studios pictures. All in all, this film is certainly worth a rental … especially so that you can tell your coworkers that you saw a movie last night called Matango: Attack of the Mushroom People!

Based on an old Buddhist fable and set during a time of war in Japan’s Middle Ages, Onibaba (or “Demon Woman”) yet tells a simple story, really. In it, we are introduced to a young woman and her middle-aged mother-in-law, who eke out a meager existence by killing lost and wounded soldiers and selling their gear for grub. The two live in a windswept grassland, its only notable feature being a dangerous pit in its center. When Hachi, a fellow soldier friend of the young woman’s deceased husband, returns home from the wars, a lustful triangle is formed between the three; a triangle that grows quite macabre when a demon-masked samurai enters the picture… Telling a story so timeless and universal that the two female characters are never even given names, Onibaba, to my great surprise, turns out to be a minor masterpiece of sorts. Frankly sexual (especially considering the year it was made: 1964), often erotic and rife with symbolism, the film is often quite startling. The three leads (Nobuko Otawa as the mother-in-law, Jitsuko Yoshimura as the lustful widow, and Kei Sato as Hachi) are uniformly superb, Kaneto Shindo’s direction is imaginative, and an outre jazz score by Hikaru Hayashi, incongruous as it might seem on paper, works marvelously. Perhaps best of all, though, is the simply stunning B&W cinematography of Kiyomi Kuroda. His shots of the swaying grassland, by night and by day, whether gently wind tossed or lashed by gale, are things of real beauty; indeed, I cannot recall being so impressed by B&W camera work to this degree in a very long time. The gorgeous images on display here boost this sexy, psychological horror show to the realm of real art, and are perfectly captured on the great-looking Criterion DVD that I recently watched. More than highly recommended, the film seems poised to amaze a new generation of viewers. Do check it out, munching on millet instead of popcorn, of course.

(Okay, I couldn’t resist … here’s yet another seldom-discussed film from Toho Studios.) Atragon, the 1963 offering from the great film-making team of director Ishiro Honda, composer Akira Ifukube and special FX master Eiji Tsuburaya, is an excellent sci-fi movie depicting a Japanese supersub’s battle with the undersea kingdom of Mu. The following year, this same team came out with Dogora, a fun if decidedly lesser effort. In this one, a single-celled organism floating in space is affected by Japan’s seemingly ubiquitous radiation and grows to become a humongous, jellyfishlike monster who lives to suck carbon off the surface of our world … along with any buildings, bridges or trucks that happen to be in the area! In a somewhat confusing plot, multiple story lines involving a group of diamond thieves, a mysterious insurance investigator, an aged expert on crystals, and a swarm of bees are conflated, with mixed results. The first time I watched Dogora (and no, we never learn the meaning or origin of this particular kurage kaiju‘s moniker), I thought the film rather hard to follow, and in all somewhat diffused. On a second viewing, the plot seemed to make more sense, but its dependence on coincidence still rather marked. One of the picture’s saving graces, for me, is the presence of Akiko Wakabayashi – with whom I first became enamored in 1967, as a result of her appearance in the James Bond blowout You Only Live Twice – here playing a moll and looking more beautiful than I have ever seen her. Dogora itself is a pleasing creation, and the sight of it whirlpooling coal into its giant maw or pulling a Kyushu bridge to bits is actually fairly awesome. Its ultimate demise is brought about in a fairly unique manner, as well. In all, not a bad little picture – actually, probably the best movie about a giant, carbon-sucking jellyfish monster from outer space that I have ever seen – as long as you don’t go in expecting anything on the order of Honda’s Gojira or The Mysterians!

![]() SNAKE WOMAN’S CURSE (1968)

SNAKE WOMAN’S CURSE (1968)

And you thought you had a lousy landlord! Just take a look at what mother Sue and daughter Asa have to put up with, in veteran director Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1968 offering, Snake Woman’s Curse. After their husband/father has been worked to death by landlord Onuma, in the village of Onuma on the shores of northern Japan at the beginning of the Meiji Period (around 1868), the two women are compelled to work in the master’s house, weaving for 16 hours a day, performing other slavelike labor, and knuckling under to the occasional sexual attack by Takeo, the “young master.” Fortunately, when these two poor women reach their physical limits and expire, their vengeance has just begun, as their spirits come back to seek a playful and haunting revenge on Onuma and his entire family. Beautifully shot and skillfully produced, Snake Woman’s Curse, though never at all frightening, still manages to please. Featuring gorgeous seaside locations and an abundance of attention to period detail, the film is great to look at, and pretty Sachiko Kuwahara is quite appealing and touching as the downtrodden Asa. After two viewings, I’m still a trifle unclear as to who the snake woman of the title is – Sue or Asa – and truth to tell, many incidents in the film go largely unexplained. The picture ultimately winds up feeling like a Japanese fable conflated with one of those old EC comics; the ones in which the spirits of the disgruntled dead take a grisly vengeance on their living malefactors. And I suppose being forced to see your new bride covered with scaly snake skin on your wedding night is a pretty good vengeance for starters, right? From first shot to its memorable final image (the spirits of the dead walking toward a rising sun), the film manages to keep the viewer focused and guessing. In all, a modestly entertaining picture that will most likely please horror fans who are game for something different…

And you thought you had a lousy landlord! Just take a look at what mother Sue and daughter Asa have to put up with, in veteran director Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1968 offering, Snake Woman’s Curse. After their husband/father has been worked to death by landlord Onuma, in the village of Onuma on the shores of northern Japan at the beginning of the Meiji Period (around 1868), the two women are compelled to work in the master’s house, weaving for 16 hours a day, performing other slavelike labor, and knuckling under to the occasional sexual attack by Takeo, the “young master.” Fortunately, when these two poor women reach their physical limits and expire, their vengeance has just begun, as their spirits come back to seek a playful and haunting revenge on Onuma and his entire family. Beautifully shot and skillfully produced, Snake Woman’s Curse, though never at all frightening, still manages to please. Featuring gorgeous seaside locations and an abundance of attention to period detail, the film is great to look at, and pretty Sachiko Kuwahara is quite appealing and touching as the downtrodden Asa. After two viewings, I’m still a trifle unclear as to who the snake woman of the title is – Sue or Asa – and truth to tell, many incidents in the film go largely unexplained. The picture ultimately winds up feeling like a Japanese fable conflated with one of those old EC comics; the ones in which the spirits of the disgruntled dead take a grisly vengeance on their living malefactors. And I suppose being forced to see your new bride covered with scaly snake skin on your wedding night is a pretty good vengeance for starters, right? From first shot to its memorable final image (the spirits of the dead walking toward a rising sun), the film manages to keep the viewer focused and guessing. In all, a modestly entertaining picture that will most likely please horror fans who are game for something different…

Director Hideo Nakata’s 1998 offering, Ringu, based on a book by the so-called “Stephen King of Japan,” Koji Suzuki, was one of the scariest movies I’ve seen in years. Thus, it was with great expectation that I popped the same team’s 2002 effort, Dark Water, into my DVD player at home. And while this latter film may not be the horror masterpiece that Ringu is, it still has much to offer. The story here concerns a newly divorced mother, Yoshimi Matsubara (sympathetically portrayed by Hitomi Kuroki), who moves into a run-down apartment building with her 5-year-old daughter, Ikuko, while at the same time starting a new job and engaging in a custody battle. We really come to care about the plight of these two characters, especially when some decidedly creepy incidents in the building start to pile up, and this gradually escalating sense of there being something “wrong” with the building turns out to be fully justified. Whereas Ringu provided us with that truly terrifying TV crawl-through scene, Dark Water offers a scene that is also absolutely guaranteed to raise the hackles on the back of any viewer’s neck (I’m thinking here of the one in the elevator near the end, natch). Similar again to Ringu, a water container turns out to be the site of a childhood tragedy, and a lank-haired ghost girl makes for one very creepy presence. Special kudos must be given here to young Rio Kanno, in her role as Ikuko. Kanno is just remarkable, and surely one of the most adorable kids I’ve ever seen on film. I’d give her a 9.8 on the Cute-O-Meter. With an involving story, excellent acting, some genuine chills and that great novelist/director pedigree mentioned above, Dark Water is a fine example of “J-horror” indeed, and if nothing else underlines the importance of having a really good building super!

So there you have it … six impressive and memorable shockers from “The Land of the Rising Sun,” each one guaranteed to give you some shudders during this Shocktober season. I hope that you will get to enjoy these as much as I did!

“Walking shitakes.” Oh, Sandy.

I’m pretty sure that DARK WATERS got an American remake a la THE RING, with an unmemorable story and a couple of good jump scares.

Onibaba sounds like something I will seek out.

“Dark Water” did indeed get an American remake, Marion…three years later, in a film starring Jennifer Connelly, Tim Roth and John C. Reilly. I’ve not seen it. Hope you do get to see and enjoy “Onibaba” one day….