SHORTS: In this week’s column we review several of the Hugo-nominated short fiction works, including four of the Retro Hugo nominees.

![]() “When We Were Starless” by Simone Heller (2018, free at Clarkesworld, $3.99 Kindle magazine issue). 2018 Hugo award nominee (novelette).

“When We Were Starless” by Simone Heller (2018, free at Clarkesworld, $3.99 Kindle magazine issue). 2018 Hugo award nominee (novelette).

In a fallen, future version of our Earth, Mink’s tribe of nomadic, intelligent lizards wanders the land, living at a bare subsistence level and frequently threatened by physical dangers, like giant verminous creatures called rustbreed. One of the tribe’s treasures is their weavers, eight-legged technological artifacts from a prior time that can turn raw materials into useful items for the tribe, like pots and tents.

Mink is both a scout and a “ghost killer” for her tribe (exactly what ghost killing involves becomes clear later in the story). So when the tribe approaches an ancient dome structure and sees some strange lights, Mink is sent to investigate and lay any ghosts in the dome to rest. In the dome she finds a most unusual ghost, one that invites her to view the various exhibits in the dome: rockets, landers … even the stars, which Mink considers a tall tale. Mink’s curiosity and love for beauty collide with her own and her tribemates’ fears and superstitions.

“When We Were Starless” is an excellent novelette with detailed worldbuilding and a memorable protagonist. It was admittedly hard for me to get into it at first, with the tribe’s superstitions veiling reality and their terminology making the story initially somewhat opaque. It took me two reads to really understand the full context of the tale and the “Shrouded Earth” world that Simone Heller has built (amusingly, in her story notes on her website, she calls this tale and an earlier, darker story set in the same world, “How Bees Fly,” “lizardpunk”).

This novelette ends with some of the same language with which it began, but elevated to a higher level. Though this world is harsh and bleak, there’s an appealing hopefulness to this novelette, a conviction that knowledge and understanding will enlighten and improve this people’s lives and overcome fears. ~Tadiana Jones

“Doorway Into Time” by C.L. Moore (originally published in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, September 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

“Doorway Into Time” by C.L. Moore (originally published in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, September 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

![]() A long-lived creature, a collector of items (including organisms) from multiple worlds, has grown jaded and bored with his museum and seeks something new. Beauty once was enough to captivate him, but now he needs danger as well, a difficulty in the collecting itself. Looking through his portal (the titular doorway) he sees a human man and woman in a lab, the man working on a device which the collector hopes is a weapon. Stepping through, he grabs the woman (Alanna) and returns. The man, Paul, follows before the portal can close, bringing his device, which is a weapon, with him. He finds Alanna alone and the two walk through the museum, their human senses mostly unable to understand what they see. When the huge, powerful collector returns, Paul turns his weapon on it. The story ends in somewhat surprising fashion.

A long-lived creature, a collector of items (including organisms) from multiple worlds, has grown jaded and bored with his museum and seeks something new. Beauty once was enough to captivate him, but now he needs danger as well, a difficulty in the collecting itself. Looking through his portal (the titular doorway) he sees a human man and woman in a lab, the man working on a device which the collector hopes is a weapon. Stepping through, he grabs the woman (Alanna) and returns. The man, Paul, follows before the portal can close, bringing his device, which is a weapon, with him. He finds Alanna alone and the two walk through the museum, their human senses mostly unable to understand what they see. When the huge, powerful collector returns, Paul turns his weapon on it. The story ends in somewhat surprising fashion.

Moore is known for her lushly romantic style, and that is on display here, beginning with the description of the collector itself, with his “great rolling limbs . . . his great bulk ponderous and graceful . . . his eyes . . . flashing many-colored under the heavy lids.” Then she turns her prose to some of the items in the collector’s home, offering up a sense of the vast strangeness of the universe:

a great oval stone whose surface exhaled a light as soft as smoke, in waves whose colors changed with languorous slowness … taken from the central pavement of a great city square upon a world whose location he had forgotten long ago. … a fountain of colored fire which he had wrecked a city to possess. … a hanging woven of unyielding crystal speaks which only his great strength could have moved.

The descriptive narrative carries you along even if it’s a bit over the top in places and somewhat repetitive in its vocabulary, while the point-of-view narrative is a bit too blunt. The encounter is suspenseful enough, and Moore turns it in an unexpected direction, though it would have been better had Alanna done more than space out, scream, and hide (at one point she is described as asking “a child’s question, her mind refusing to accept anything but the barest essentials of their predicament.” Having this written by a hugely successful female author makes this bite all the more. If you like your old-style pulp space romance, this will scratch that itch nicely. ~Bill Capossere

![]() The evocative, portentous descriptions of the heedlessly selfish alien collector and his gorgeous (and sometimes appalling) house of treasures with its razor-edged floor is, I think, the best part of this 1943 story by C.L. Moore. As the story developed I thought it devolved into a somewhat standard man vs. monster confrontation, complete with a lovely, helpless heroine who obligingly screams, shakes and even (shudder) whimpers. But the way this story wrapped up wasn’t as typical, with an interesting ambiguity to the fate of the human pair. Moore’s enviable prose also bumps this story up a notch. ~Tadiana Jones

The evocative, portentous descriptions of the heedlessly selfish alien collector and his gorgeous (and sometimes appalling) house of treasures with its razor-edged floor is, I think, the best part of this 1943 story by C.L. Moore. As the story developed I thought it devolved into a somewhat standard man vs. monster confrontation, complete with a lovely, helpless heroine who obligingly screams, shakes and even (shudder) whimpers. But the way this story wrapped up wasn’t as typical, with an interesting ambiguity to the fate of the human pair. Moore’s enviable prose also bumps this story up a notch. ~Tadiana Jones

“Exile” by Edmond Hamilton (originally published in Super Science Stories, May 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

“Exile” by Edmond Hamilton (originally published in Super Science Stories, May 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

![]() The May ’43 issue of the pulp magazine known as Super Science Stories, sold for 25 cents, boasted a beautiful piece of artwork on its cover by famed illustrator Virgil Finlay, a short novel called Legion of the Dark by Manly Wade Wellman, a short story called “Reader, I Hate You” by the great Henry Kuttner, and an essay by German scientist and science writer Willy Ley … among other items. All of these pieces have been largely forgotten over the intervening 76 years, whether justly or not. But it is the short story that was tucked away on page 88 of this issue, Edmond Hamilton’s “Exile,” that stands the best chance of attaining to long-term fame, for the simple reason that it has been nominated for a Retro Hugo Award (Best Short Story, 1943) this year.

The May ’43 issue of the pulp magazine known as Super Science Stories, sold for 25 cents, boasted a beautiful piece of artwork on its cover by famed illustrator Virgil Finlay, a short novel called Legion of the Dark by Manly Wade Wellman, a short story called “Reader, I Hate You” by the great Henry Kuttner, and an essay by German scientist and science writer Willy Ley … among other items. All of these pieces have been largely forgotten over the intervening 76 years, whether justly or not. But it is the short story that was tucked away on page 88 of this issue, Edmond Hamilton’s “Exile,” that stands the best chance of attaining to long-term fame, for the simple reason that it has been nominated for a Retro Hugo Award (Best Short Story, 1943) this year.

In truth, it is a rather atypical kind of story for Hamilton to be singled out for. With his nickname of “the World Wrecker,” Hamilton specialized in tales of action, adventure and thunderous space opera, in many of which (true to his sobriquet) entire planets get blown up (real good). “Exile,” on the other hand, is a quiet story, as compact and flabless as can be. The entire tale runs to five pages (I refer here to the page length in my 1977 collection The Best of Edmond Hamilton; an absolutely marvelous collection, by the way), although it was likely fewer than that in the pages of Super Science Stories.

In the story, four science fiction writers ― the narrator being Hamilton himself, I’d imagine ― are seen having drinks after dinner one evening, and one of them, Carrick, tells the others a most unusual tale. He’d moved next to a large power station on the edge of the city, and had started working on a new sci-fi series. He’d plotted out the precise details of his imaginary planet, and then became aware of a feeling of “crystallization,” telling the others that he “had a sudden strong conviction that it meant that the universe and world I had been dreaming up all day had suddenly crystallized into physical existence somewhere”! He’d proceeded to supply his world with a history and various civilizations, only to feel that same peculiar effect. Eventually, Carrick came to realize that the nearby power plant was somehow sending out energies that caused his very thoughts to convert to concrete reality! On a whim, he’d attempted to imagine himself into that made-up world of his … and had succeeded! The only trouble was, Carrick tells the others, that he had become trapped therein, with little hope of return…

“Exile,” brief as it is, remains a haunting little story, and its surprising twist ending is a highly pleasing one. It more than holds its own in that Best of collection amongst such terrific and oft-anthologized stories as “The Man Who Evolved,” “A Conquest of Two Worlds,” “Thundering Worlds,” “The Man Who Returned” (a masterpiece, sez me), “He That Hath Wings” (another masterpiece, I’d say), “What’s It Like Out There?” and the beautiful “Requiem.” (I’m getting myself in the mood to reread that entire 400-page book as I write these words!) But is it worthy of that Retro Hugo?

Well, I suppose that I’m not really in a position to say. The story is up against some real competition, for one thing, most of which I haven’t read. Those competing stories are Isaac Asimov’s “Death Sentence,” C.L. Moore’s “Doorway Into Time,” Ray Bradbury’s “King of the Gray Spaces” (aka “R Is for Rocket”), “Q.U.R.” by H. H. Holmes (a pen name of Anthony Boucher), and Robert Bloch’s “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” (the only other story of these six that I have read). I told you it was some pretty serious competition! Personally speaking, I happen to just love all six of these authors, and would be happy to see any of them win. The Bloch piece has likely been the most often anthologized, although that is probably no predictor in this award category. But whichever story manages to cop the prize this August, I very much doubt that it will be as pithy or concise as Edmond Hamilton’s “Exile.” ~ Sandy Ferber

![]() It pains me to disagree with Sandy, but I thought that “Exile” was a forgettable story, overly reliant on the sudden, shocking twist ending that characterizes so many of the older pulp science fiction stories, and that Bill (rightly) takes Asimov’s “Death Sentence” to task for below. ~Tadiana Jones

It pains me to disagree with Sandy, but I thought that “Exile” was a forgettable story, overly reliant on the sudden, shocking twist ending that characterizes so many of the older pulp science fiction stories, and that Bill (rightly) takes Asimov’s “Death Sentence” to task for below. ~Tadiana Jones

“King of the Gray Spaces” (later retitled “R is for Rocket”) by Ray Bradbury (Famous Fantastic Mysteries, December 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

“King of the Gray Spaces” (later retitled “R is for Rocket”) by Ray Bradbury (Famous Fantastic Mysteries, December 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

![]() A pair of 15-year-old best-friend boys yearn to be chosen as astronauts, which happens only rarely and not at all past the age of 20. When one is selected, the two realize they’ll have to separate, at least for a while.

A pair of 15-year-old best-friend boys yearn to be chosen as astronauts, which happens only rarely and not at all past the age of 20. When one is selected, the two realize they’ll have to separate, at least for a while.

This story is classic Bradbury — an ache for the stars, a loss of childhood, a focus on young boys’ friendships, a passive woman, lushly lyrical and fragmentary prose, and little science. Typically, Bradbury doesn’t do much world-building beyond a few throw-away lines, such as neighbors all having paralysis guns (gee, can’t see any problems with that concept), weather control, and, more disturbingly though it isn’t presented as such (which is un-Bradbury like), “psychological laundering.” It’s all sentimental and nostalgic and bittersweet and kids are running everywhere rather than walking and punching each other in the shoulders to show emotion and vowing to stay friends forever. In short, quintessential Bradbury, if not his best work. ~Bill Capossere

![]() Bill’s review perfectly encapsulates Bradbury’s “King of the Gray Spaces” (I still have trouble not thinking of it as “R is for Rocket”). It is sentimental and nostalgic, but Bradbury’s poetic writing makes the story of Chris and Ralph and their dreams of rockets and space hit home for me. So much is unsaid, but nevertheless understood, between Chris and Ralph, and Chris and his mother Jhene. It’s a fine story of the loss that can often accompany reaching for your dream. ~Tadiana Jones

Bill’s review perfectly encapsulates Bradbury’s “King of the Gray Spaces” (I still have trouble not thinking of it as “R is for Rocket”). It is sentimental and nostalgic, but Bradbury’s poetic writing makes the story of Chris and Ralph and their dreams of rockets and space hit home for me. So much is unsaid, but nevertheless understood, between Chris and Ralph, and Chris and his mother Jhene. It’s a fine story of the loss that can often accompany reaching for your dream. ~Tadiana Jones

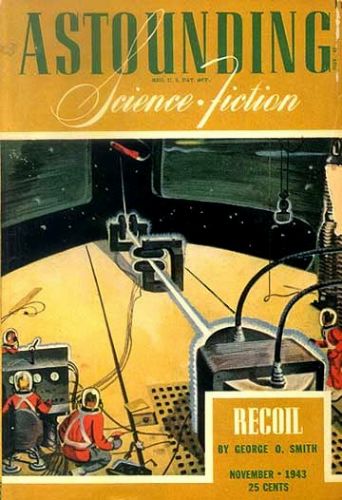

![]() “Death Sentence” by Isaac Asimov (Astounding Science Fiction, November 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

“Death Sentence” by Isaac Asimov (Astounding Science Fiction, November 1943). 1944 Retro Hugo award nominee (short story).

A “misfit” amateur researcher, Theo Realo, has made the astounding discovery of an ancient Galactic Foundation that created an experiment where they populated a world solely with robots to see how they would develop. Realo, after finding the evidence of the Foundation and the robot world on the planet of Dorlis, has spent the past 25 years on the out-of-the-way robot world itself. On his return, an academic research team is sent to Dorlis, accompanied by a government official whom the academics do not trust. Once Realo’s find is confirmed, the academics and the government disagree on what to do next.

This is one of those classic old-style sci-fi stories that relies quite a bit on the “shocker” of an ending, which really, once one has read a few of them, isn’t a shocker at all, and in fact is easy to guess way early (it’s the kind of story magazines occasionally say not to send them nowadays). It’s also pretty typical of Asimov’s early work. Women don’t appear, but lots of cigars and cigarettes do. Characterization is non-existent: the government official sees the robots as a threat because he’s a government official, the academics want to research because they’re academics, Realo makes poor decisions because he’s an albino misfit, a “queer” type. All the characters are summed up in two or three words. Plot moves apace with abrupt shifts. And there is no real attempt to dig more deeply at the ethical/philosophical questions the situation raises. Not a story that ages well. ~Bill Capossere

I loved this deep dive into Edwige Fenech's Giallo films! Her performances add such a unique flavor to the genre.…

It would give me very great pleasure to personally destroy every single copy of those first two J. J. Abrams…

Agree! And a perfect ending, too.

I may be embarrassing myself by repeating something I already posted here, but Thomas Pynchon has a new novel scheduled…

[…] Tales (Fantasy Literature): John Martin Leahy was born in Washington State in 1886 and, during his five-year career as…