![]() Shadows in the Sun by Chad Oliver

Shadows in the Sun by Chad Oliver

Although it’s been almost seven years since I read Chad Oliver’s masterful fourth novel, Unearthly Neighbors (1960), such are the evocative atmosphere and compelling alien depictions in that book that I still manage to remember it quite well. And indeed, Unearthly Neighbors just might be the most convincingly realistic description of “first contact” on another world that a reader could ever hope to encounter. I’ve been wanting to check out more of the Cincinnati-born author ever since, and fortunately picked up one of his earlier works, Shadows in the Sun, as my next Chad Oliver experience; a very good choice, as things have turned out!

Although it’s been almost seven years since I read Chad Oliver’s masterful fourth novel, Unearthly Neighbors (1960), such are the evocative atmosphere and compelling alien depictions in that book that I still manage to remember it quite well. And indeed, Unearthly Neighbors just might be the most convincingly realistic description of “first contact” on another world that a reader could ever hope to encounter. I’ve been wanting to check out more of the Cincinnati-born author ever since, and fortunately picked up one of his earlier works, Shadows in the Sun, as my next Chad Oliver experience; a very good choice, as things have turned out!

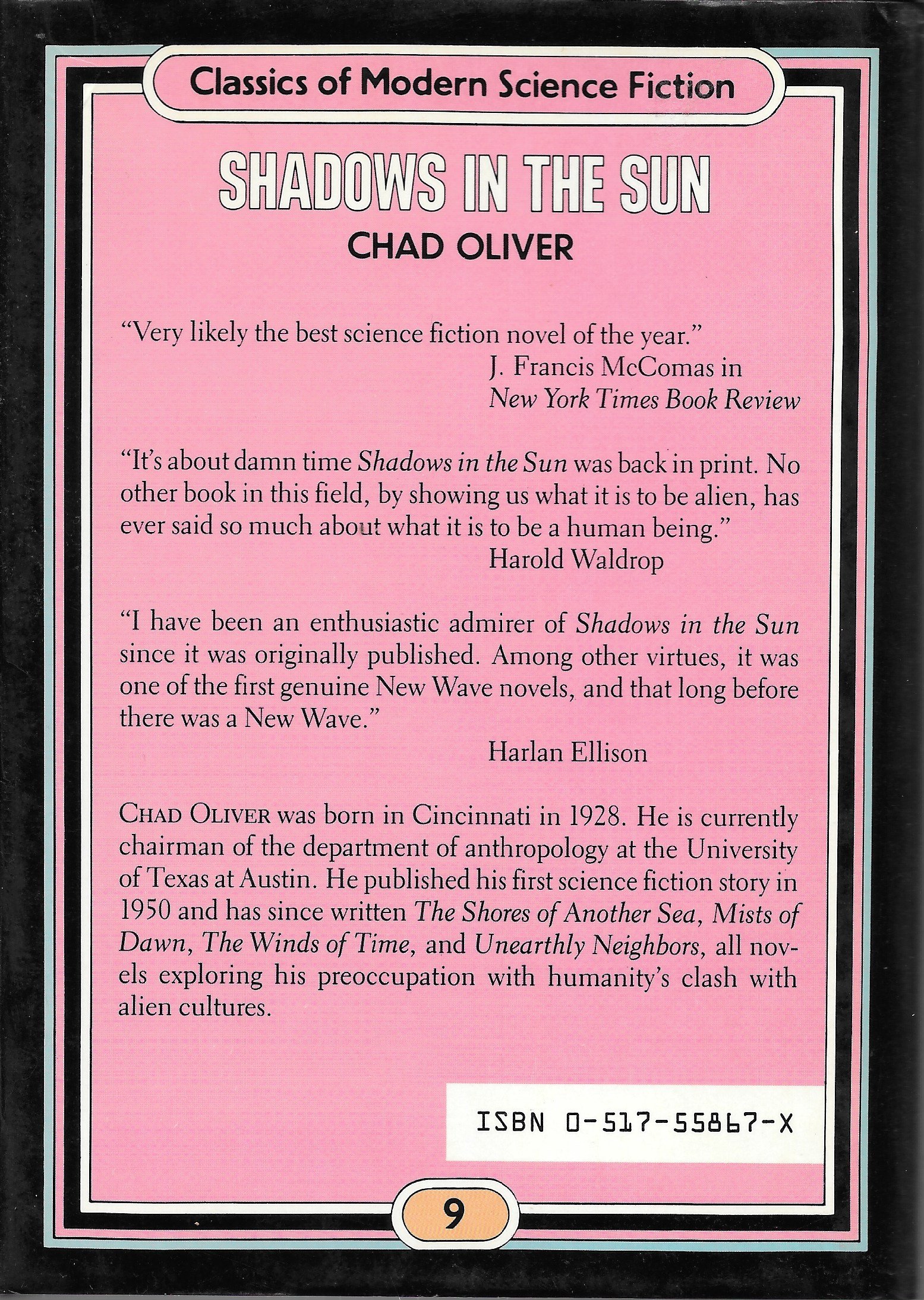

Shadows in the Sun was Oliver’s second novel and his first one written for an adult audience. His debut novel, the highly regarded “juvenile” entitled Mists of Dawn, had been released in 1952; one of 37 YA sci-fi works in the renowned John Winston Co. series. Shadows in the Sun would be released two years later, in December 1954, as both a $2 Ballantine hardcover and, simultaneously, as a 35-cent Ballantine paperback; Oliver was 26 at the time, and seven years away from getting his Ph.D. in anthropology at the University of California. The book would be given another hardcover treatment by the British publisher Max Reinhardt in ’55, become a French paperback in ’56, an Argentinian paperback in ’57, a British paperback in ’65, and a German paperback in ’67 (bearing the altered title Die Vom Anderen Stern, or Those From the Other Star). Ballantine would rerelease the book in 1968 as a 50-cent paperback, and then … OOPs (out of prints) for 17 years, until Crown Publishers opted to resurrect it as one of the entries in its Classics of Modern Science Fiction series, in a cute little hardback with a Michael Booth cover, in 1985. And this is the edition that I was fortunate enough to lay my hands on. Like Unearthly Neighbors, also in this series, the book features a scholarly introduction by George Zebrowski and, even better, a highly informative afterword by Chad Oliver himself, written eight years before his untimely passing in 1993, at age 65. The author would ultimately write four sci-fi short story collections as well as nine novels (that juvenile sci-fi, five adult sci-fi, and three Westerns), and of those many works, as he reveals in his afterword here, Shadows in the Sun is the book that is “closest to [his] heart.” And with its autobiographical elements and a story line that is set in an environment that the author obviously knew all too well, it is easy to understand why.

Oliver’s book introduces us to an anthropology professor named Paul Ellery, who has taken a leave of absence from his post at the University of Texas at Austin to engage in a research project. Thus, we encounter him in the little burg of Jefferson Springs, TX, doing a study of life in small-town America, and at the end of two months there, when we first meet him, Ellery is a very confused man. Things in Jefferson Springs just don’t seem to add up. For one thing, although the town has been in existence for 132 years, none of its 6,000 residents has been there for longer than 15. The people there seem oddly off, their houses staying unlit at night, and the whole environment comes off as being somewhat too pat and contrived. Although the townsfolk do open up to Ellery after initially being decidedly unfriendly, the scientist senses that they are all play-acting. And then one night, he sees a metallic sphere descend from an enormous hovering spaceship above rancher Melvin Thorne’s house, and Thorne and several others emerge. (And no, this is hardly a spoiler; it transpires on page 16 of the novel.) Paul is understandably aghast at the sight, and brazenly knocks on the rancher’s door to demand answers, only to be given the innocent act by the seeming Texan. But a little while later, two men arrive at Paul’s hotel room, bring him into the countryside, and take him, by that same metallic sphere, up to the mother ship, where our anthropologist hero meets a fat little red-faced man named “John,” who explains to him what’s been going on.

John, it seems, is an expert of sorts at getting to know planetary natives. He tells Paul that yes, he comes from an Earth-like planet that is part of a galactic federation. Apparently, there are any number of Earth-like planets out there, each of which has produced beings just like Homo sapiens. But those planets have all reached the point of overpopulation, and so now the federation is surreptitiously depositing its overflow on even the comparatively primitive and unoccupied habitable worlds that it can find, such as ours. Jefferson Springs is just one of many such alien enclaves around our planet, and the galactic settlers, far from being hostile invaders, wish to only live in peace and isolation, and indeed have laws forbidding the use of violence and interference in native affairs. Recognizing Paul’s special abilities as a scientist, John even offers him the chance of becoming one of them; of being given special training and education at some Center far away, and then a resettlement, perhaps on Earth, perhaps elsewhere. Thus, for the duration of Oliver’s book, we see Paul struggle with the question of what is best for him to do. We watch as he takes a mandatory job in Jefferson Springs, working on its small newspaper; as he enters into an affair with the beautiful blonde alien schoolteacher named Cynthia; as he attends an outdoor communion rite with the other settlers; as he confusedly returns to Austin to be with his old girlfriend, Anne; and as he further agonizes over his big decision, and the New Year’s Eve deadline for that decision draws ever closer…

John, it seems, is an expert of sorts at getting to know planetary natives. He tells Paul that yes, he comes from an Earth-like planet that is part of a galactic federation. Apparently, there are any number of Earth-like planets out there, each of which has produced beings just like Homo sapiens. But those planets have all reached the point of overpopulation, and so now the federation is surreptitiously depositing its overflow on even the comparatively primitive and unoccupied habitable worlds that it can find, such as ours. Jefferson Springs is just one of many such alien enclaves around our planet, and the galactic settlers, far from being hostile invaders, wish to only live in peace and isolation, and indeed have laws forbidding the use of violence and interference in native affairs. Recognizing Paul’s special abilities as a scientist, John even offers him the chance of becoming one of them; of being given special training and education at some Center far away, and then a resettlement, perhaps on Earth, perhaps elsewhere. Thus, for the duration of Oliver’s book, we see Paul struggle with the question of what is best for him to do. We watch as he takes a mandatory job in Jefferson Springs, working on its small newspaper; as he enters into an affair with the beautiful blonde alien schoolteacher named Cynthia; as he attends an outdoor communion rite with the other settlers; as he confusedly returns to Austin to be with his old girlfriend, Anne; and as he further agonizes over his big decision, and the New Year’s Eve deadline for that decision draws ever closer…

Now, whereas in another “alien invasion” novel the reader might feel concern for the safety of the protagonist, interestingly, that is hardly the case here. Paul Ellery is at no point in any danger whatsoever from these alien settlers – they are not the pod people of Jack Finney’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or the murderous visitors from TV’s wonderful ‘60s show The Invaders. In Oliver’s book, the suspense comes from our uncertainty as to Paul’s big decision, and the author keeps us guessing as to that life-changing decision till practically the very last page. The book does provide some good food for debate; some readers will certainly not agree with the tough choice that Ellery makes on that penultimate page. Readers should also not be looking for any hints of strangeness amongst those aliens, either; as John makes a point of telling Ellery, they’re pretty much just like us, despite their space flight capabilities. These are hardly the sci-fi supermen of pulp literature that John makes a point of decrying; “no monsters, no fiends, no wicked prime ministers,” as he describes his culture to Paul. What little “cosmic awe” there is to be had in Oliver’s book comes from Paul’s glimpse, in a futuristic cinema on board the alien vessel, of The Others: oozing, slimy, undulating things that flap through space and attack starships, the mere sight of which causes Ellery to scream in fright, and a menace that the worlds of our galaxy will need to eventually face one day together.

Oliver was one of the earliest writers – perhaps the earliest – in the literary genre now known as anthropological science fiction, and his young enthusiasm in his chosen field is very much in evidence here. He references some of the famous anthropologists and scientists who he’d been influenced by, such as (James) West, (W. Lloyd) Warner, Clyde Kluckhohn, (Hortense) Powdermaker, (Robert) Redfield, (Alfred) Kroeber, (William) Howells, V. Gordon Childe, (Leslie) White, (Bronislaw) Malinowski and (Ralph) Linton, and the subject of acculturation – the change that occurs in individuals when two cultures collide – is at the very heart of his book. And indeed, Paul very early comes to realize that he is the primitive aborigine here, and the starmen something on the order of the 16th century European colonials. The book poses and goes far in answering some interesting questions, such as: How can a person assimilate into a culture and yet remain who he/she is? Is it more important to go out into the cosmos or remain here and learn more about yourself and your own culture? Do technical achievements turn a people into a race of supermen? Should an invading culture leave a more primitive culture alone or try to influence its development? And Oliver tackles these weighty issues in a very engaging manner, indeed.

I mentioned earlier that this book is somewhat autobiographical in nature, and that is surely true … up to a point. Like Ellery, Chad Oliver was a big husky anthropologist who taught at the University of Texas at Austin. Both were pipe smokers, and both were fans of 1940s jazz (Oliver was even a DJ at a jazz station in the mid-‘50s). And as the author tells us in his afterword, after moving with his family to Crystal City, TX (some 30 miles south of Uvalde) when he was 15 years old and in high school, he felt like something of an alien there … just as Paul does in Jefferson Springs. And the author’s intimate knowledge of both Austin and the Hill Country is on full display here, both of which are wonderfully described.

I mentioned earlier that this book is somewhat autobiographical in nature, and that is surely true … up to a point. Like Ellery, Chad Oliver was a big husky anthropologist who taught at the University of Texas at Austin. Both were pipe smokers, and both were fans of 1940s jazz (Oliver was even a DJ at a jazz station in the mid-‘50s). And as the author tells us in his afterword, after moving with his family to Crystal City, TX (some 30 miles south of Uvalde) when he was 15 years old and in high school, he felt like something of an alien there … just as Paul does in Jefferson Springs. And the author’s intimate knowledge of both Austin and the Hill Country is on full display here, both of which are wonderfully described.

Oliver’s book is compulsively readable, unfailingly intelligent, and warmhearted, with credible characters and finely rendered dialogue. The author, here in his first novel for an adult audience, evinces a joy in language, his simply written but elegant prose almost coming off like that of Hemingway (of whom Oliver was an admitted fan). This is a book that aspires to the realms of quality literature. We are given lines such as:

…The blazing white sun hung in the sky, almost motionless, as though it too were too hot to move. No cloud braved that furnace, and the heat beat down like boiled, invisible rain. Heat waves shimmered like glass in the still air and the parched earth took on the consistency of forgotten pottery…

Oliver also throws in any number of dryly humorous lines, such as when Cynthia yells across a room and Paul reflects “She had a good pair of lungs, among other things,” and when Ellery deems rancher Thorne “a Texas Babbitt from another planet.” Any number of finely written sequences crop up, especially Paul’s initial interview with Thorne; his first meeting with John aboard the starship; that very unusual outdoor communion, with all 6,000 Jefferson Springs residents in attendance; Ellery’s tour of the starship; and, of course, the days leading up to Paul’s big decision. Oliver, a confessed fan of science fiction from childhood, also takes some digs at the genre, as when John opines:

…There’s a whole literature down here that’s positively stuffed with invading monsters, ghouls, and a frightfully dull army of dim-witted supermen who dash about through the air thinking at each other and throwing things about with mental force, whatever that is … Deplorable. The worser sort, that is…

And, I might add, Oliver’s book is, surprisingly, sexually frank, especially for 1954. Cynthia and Paul’s relationship is blatantly sexual in nature, despite the fact that Anne, Paul’s longtime “steady,” is waiting for her man impatiently at home. So yes, this really is at bottom a sci-fi novel for thinking adults, and one that consistently confounds the reader’s expectations throughout.

I actually have hardly one quibble to lodge against Oliver’s very fine work here. But if I were forced to make a single complaint, it is that the location given for Jefferson Springs (120 miles south of San Antonio and 60 miles north of Eagle Pass) does not actually make sense when one looks at a map of Texas; perhaps the author was endeavoring to be vague here, so as not to draw too fine a comparison between the fictitious town and his boyhood home of Crystal City. But really, that’s about it. Shadows in the Sun is a wonderful read, and one that I can recommend highly. It is “very likely the best science fiction novel of the year,” said sci-fi editor J. Francis McComas in his New York Times Book Review – a year, mind you, that also gave us Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, Edgar Pangborn’s A Mirror for Observers, Robert A. Heinlein’s The Star Beast, Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel and Murray Leinster’s The Forgotten Planet – and darn it, he may be right! I now find myself wanting to read the third Oliver title in Crown’s Classics of Modern Science Fiction series, namely The Shores of Another Sea, from 1971, and fortunately, that book has also been sitting patiently in my bookcase for a good long while. Rather than wait another seven years for my next Chad Oliver experience, I do believe that that is where I will be heading next. Stay tuned…

“…no wicked prime ministers.” So not very much like us then.

Sadly true….