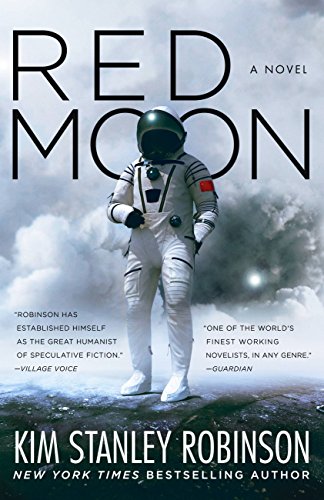

![]() Red Moon by Kim Stanley Robinson

Red Moon by Kim Stanley Robinson

I’m a big fan of most of Kim Stanley Robinson’s output, especially his MARS trilogy, and so when I saw that he was out with a book entitled Red Moon (2018), with its echoes of said trilogy (Red, Green, and Blue Mars), that it had an AI character like Aurora, another favorite work of his, and that it came with a heavy dose of politics, which I’ve enjoyed in all his prior work, I was thinking all I was missing was a Neandertal (seen in his brilliant Shaman) to have the perfect Robinson novel. Unfortunately, the whole turned out to be less than the sum of its parts for me.

Red Moon is set in the relatively near future where the moon has been colonized, mostly by China, but also in smaller fashion by other governments (the US, Brazil, India, etc.) as well as by various billionaires. Fred Fredericks, a quantum tech, is delivering a quantum phone to the Chinese governor on the moon, Chang Yazu, but things go horribly awry when Chang is apparently murdered, and Fred is blamed for it. One would think the main tension would be between the Americans (given that Fred is an American citizen) and the Chinese, but in reality, the tension lies amongst the many factions vying for control in this fragile time of change in China when the new President is about to be chosen and immigrants/workers are pressing for reform. One of the leaders of that reform movement is Qi, a young pregnant Chinese “princess,” the daughter of a rich and Party-connected official who is a potential nominee to lead the country. In keeping with the theme signposted by Fred’s position, he and Qi become “entangled” and soon go on the run and into hiding, both on the moon, then on Earth, then back on the moon. All as events on Earth, where China and America (the “G2” as they’re called) are also so entangled that events in one are affecting events in the other, as well as having global impact.

The ideas that Robinson explores here are fascinating and, given their near-future possibility (or certainty/likelihood for some), important to think about. China’s growing role as a superpower, the surveillance society, humanity’s environmental impact, the potential of AI, the impact of cryptocurrency, rising anger by “the people” over their lack of representation in the circles of power, how countries keep their sense of identity in a rapidly changing world (and should they even try). The thoughtfulness of Red Moon is definitely one of its strengths.

But a book needs to be more than a compendium of ideas. And it’s in the more basic elements that Red Moon failed me: character and plotting. Neither character came fully alive for me at any point throughout the story. In theory, they’re each interesting. Fred seems to be somewhere on the spectrum and has clear difficulty in engaging with people. But while his slow movement toward change in this regard is a positive, there’s mostly little to hold onto with him. He just doesn’t seem to have much of a personality, which is compounded by his utter passivity through most of the story. Qi, as a princess leading a people’s revolution, should be much more compelling than she is, but again, falls short of her potential. It’s hard to square the personality and strength she must have to fulfill her role as inspiring leader with much of what we see her do (or not do) in the story itself. The only character that did come alive for me was the poet/media star Ta Shu. But somewhat telling, the strongest, best, most moving part of his story has nothing to do with the main plot at all, but involves his interaction with his elderly mother. It’s in those few scenes where you see Robinson’s talent at creating richly felt characters of feeling and see, as well, how those moments stand in contrast to the reset of the novel.

The plot, meanwhile, is repetitive, with it being a case of run-hide-get-caught-run-hide-rinse and repeat. It doesn’t help that Red Moon is a very talky book, with long digressions with characters reading or expounding on ideas in ways that feel artificial and clunky, whether they involve infrastructure, feng shui, quantum science, bamboo, Mao, or other topics that the readers need explained (or that Robinson just likes to explain). I suppose one could argue that the repetition, digression, and all the sitting around doing nothing but waiting while eating and sleeping mirrors much of life. But most people don’t come to fiction for an exact mirroring of the duller parts of living. They want a story. Here, it feels like Robinson didn’t want to bother with that part. The plot (as opposed to story) serves the goal of Robinson telling us stuff he believes we should be thinking about. Granted, that’s not unusual for authors, but usually the execution does a better job of hiding that, whether it’s behind rich, deeply felt characters or things blowing up. We get too little of either in this case.

I’d think I’d rather just go listen to Kim Stanley Robinson speak on any one of these topics, because he also a thoughtful, fascinating lecturer.

Agreed. This sounds like it might have worked better as a good series of essays expounding on Robinson’s ideas without the characters cluttering things up.