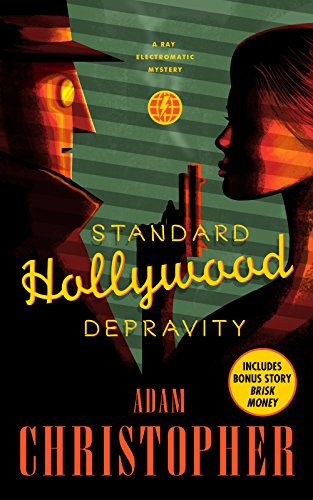

![]() Made to Kill by Adam Christopher

Made to Kill by Adam Christopher

In his afterword to his new novel Made to Kill, Adam Christopher explains how the idea first saw life as a long short story/novelette entitled “Brisk Money.” While this more extensive take on the story is still relatively slim for a novel, coming in at just over 200 pages, I have to admit that it seemed to me that Christopher would have been better off simply writing another “episode” of his narrative via another short story rather than trying to expand the original into something larger.

That original story germinated out of a question from a Tor roundtable: “If you could find one previously undiscovered book by a nonliving author, who would it be?” Christopher, a huge Raymond Chandler fan, thought he’d like to read Chandler’s “lost science-fiction epic” (Chandler famously hated the genre).

And so we have Made to Kill, a Chandler-esque tale, albeit with a 6’10” robot as the hard-nosed PI. The setting is Chandler’s mid-1960’s L.A., and like all good noir tales, this one starts off with a mysterious dame appearing at the door of the PI with a request. Our “hero,” Raymond Electromatic, is the last of the robots (they turned out to be a failed techno-social experiment, though Ray is a bit unique) and works as a PI by day and a hitman by night, though really he isn’t averse to some killing while the sun’s out — whatever pays the bills. The brains of the business is an AI named Ada (as in Ada Lovelace, early computer pioneer), who gets their jobs, finds information, and sets Raymond straight as to what happened the prior day, a task necessitated by the inconvenient fact that Raymond’s memory tapes only holds 24 hours, and so each morning he “wakes” without knowledge of what happened the day before.

oses of capturing the Chandler voice, over time some of the lines began to feel forced and repetitive. There were far too many similes (often centering on the same action, such as Raymond’s noises or Ada sounding like she was smoking) and at times the vocabulary didn’t seem true to the character, as when Raymond tossed around words like “lug” or “cat.” In those instances, he felt more like a robot programmed to sound like a Chandler narrator (or a character “programmed” by an author to do so) than a robot programmed with his creator’s personality as a template, which is what he is. And while I did like Raymond’s grey nature, it’s also true that it being a product of his software, with little sense of the possibility of change or little sense of introspection, robbed this quality of some of its power, as such lack of agency is almost always less interesting.

As mentioned, that detail about his inability to recall past events added some tension, but beyond that, it felt like it fell short of its rich potential. I kept waiting for it to play much more of a role in the plot. As for the plot, it just became more and more absurd so that one began to wonder if Christopher was moving from homage into over-the-top parody. Especially in his villains, who were wholly cartoonish. Worse though, were all the plot holes which led me on more than a few occasions to write in my notes, “But why didn’t he just…“ or “Why would he…“ or “Wouldn’t she just…“

I have not read Christopher’s original story. I’m guessing that many of these flaws are either missing entirely or are far less distracting. I can see how a short story, or an episodic series of said stories, would work with both this style and character, but in Made to Kill, the form and its content are too mismatched and the elements are stretched to their breaking point and beyond.

I actually just finished reading this! I had almost the exact same reaction to it, too.