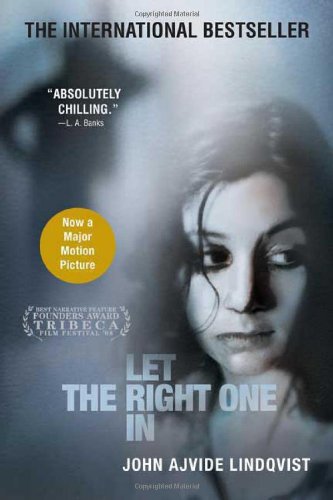

![]() Let the Right One In by John Ajvide Lindqvist

Let the Right One In by John Ajvide Lindqvist

Let the Right One In, by John Ajvide Lindqvist, is a bleak and chilly horror novel that evokes classic Stephen King works like Salem’s Lot. Lindqvist is a Swedish writer and the book is set in a planned community in northern Sweden, called Blackeberg, in 1981. The novel follows several different point of view characters as the events that will change the community forever begin to unfold.

From the beginning, Lindqvist wants the reader to understand Blackeberg.

It was not a place that developed organically, of course. Here everything was carefully planned from the outset. And people moved into what had been built for them. Earth-colored concrete buildings scattered about the green fields.

Part of the atmosphere of the novel, and its bleakness, stem from the ideal vision of Blackeberg, created in the 1950s, and the dreary reality of it in 1981, with high unemployment, a nanny-state government, and understandable paranoia about the Soviet Union. The book introduces a group of drunks who congregate at a Chinese restaurant; a young hoodlum-in-training whose mother is engaged to a policeman; a boy with a fractured home life and a strange, haunted man, Hakan, who is the guardian and jailer of the young girl named Eli.

The heart of the story, though, is the boy, Oskar, and his blossoming friendship with Eli. Oskar lives in one of the housing complexes in Blackeberg with his mother. His father, who is an alcoholic, lives far away. Oskar has become the target of the school bullies. His mother is overprotective in the ways that don’t matter — always telling him to wear his hat — but she has no idea what her son is really confronting. Oskar keeps a scrapbook of serial killers, shoplifts to feel some sense of power, and indulges in more and more violent fantasies. Then a boy is killed in the forest not far from Blackeberg, and serial killers become a reality for him.

Oskar meets Eli, the strange little girl from next door. She can brave the cold with only a thin, short-sleeved sweater; she is incredibly athletic; her way of speaking is strange, as if she doesn’t know modern slang or current events. She is home-schooled by Hakan, a man she identifies as her father. He is not her father. He is the man who killed the boy in the forest, and is planning to kill more people and drain them of blood — blood Eli needs in order to survive.

Eli was twelve years old when she was transformed into the thing she is, and she must always depend on someone to travel with her, protect her while she sleeps during the day and bring her blood. It is a precarious existence. As horrifying as Eli’s nature is the window into her relationship with Hakan, who harbors fantasies of sex with young children and believes that he loves Eli.

When Hakan is unable to bring her blood, Eli hunts on her own, killing one of a group of barflies. Hakan disposes of the body, but the other alcoholics suspect something is wrong and begin to investigate.

Oskar is more focused on his own problems. The hazing and bullying he endures is growing worse. Lindqvist writes about bullying as well as King did in several of his books. At the beginning of Let the Right One In, Oskar humiliates himself in front of his tormentors, squealing and grunting like a pig, to avoid a beating. There is no rational reason for the attacks on Oskar. He has just been chosen, and his former friends have drifted away from him. Eli, though, tells him to fight back, and Oskar begins to get stronger.

One of this novel’s strengths is the depiction of the various facets of Eli’s nature. She is a child. She tells Oskar that she even though she has been alive for more than two hundred years, she always feels twelve. She is not maturing. Her friendship with Oskar seems genuine, but we have also watched her bargain with and manipulate Hakan. We also see her hunt. To nourish her, the blood she consumes has to come from a live human body, not animal blood, not blood from a dead person. If Eli does not break the neck or otherwise destroy the body, the person whose blood she drank will become what she is. Eli can fly and has retractable claws that allow her to scale buildings. She is a monster, but we have empathy for her.

The most tragic story arc in the book is that of Lacke, one of the drinkers, and Virginia. Virginia is a truly innocent victim, and the lost opportunity between these two damaged souls is heart-breaking. Eli is interrupted when she feeds off Virginia, and over the period of a day Virginia transforms. This allows Lindqvist to show the reader the mechanics of his vampire. Virginia’s resolution, once she understands the truth, is terrifying and heroic.

Young practicing criminal Tommy and his sparring match with his mother’s fiancé, the pious control-freak policeman Staffan, add another level to the book.

“Tommy’s mom grabbed him by the elbow and whispered, ‘Why do you say things like that?’

‘I was just wondering.’

‘He’s a good person, Tommy.’

‘Yes, he must be. I mean, with prizes for pistol shooting and the Virgin Mary. Could it get any better?’”

The heart of the book, though, is the sweet friendship between Eli and Oskar. Even when he knows what she is, Oskar stands by her. And when he confronts the bullies and the attacks on him escalate, Eli is the only one he can count on.

This is a horror novel, and there is no way it can end well. In spite of that I was rooting for Oskar and Eli to survive, even though their futures, if they did, would be grim and hellish. The real horror here, beautifully captured, is the sense that Oskar and Eli live lives of complete isolation. Oskar’s life is the difference between the ideal and the reality of Blackeberg.

Ebba Segerberg translated the edition I read, but I never felt like I was reading a translation. The English prose is assured and vigorous. This is an unusual version of a vampire story. Let the Right One In is as dark as a winter solstice night in a Norrland forest.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks