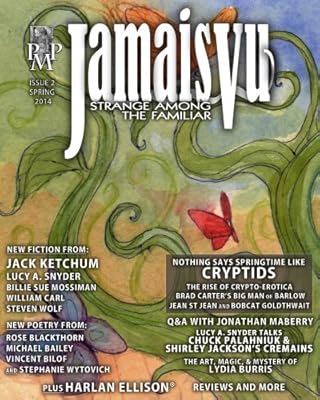

Issue Two of Jamais Vu does not fulfill the promise of Issue One (reviewed here).

Issue Two of Jamais Vu does not fulfill the promise of Issue One (reviewed here).

“Valedictorian” by Steven Wolf is a post-apocalypse story, though there is no hint exactly what happened; we only know that few have survived, none of them adults, and the world is littered with dead bodies. Wolf’s first-person narrator is a high-school-aged boy who, with his friend Gretchen, shows up at the local high school every school day. Gretchen is the one who insists on this, and she engages in serious self-study. The narrator just sleeps, although he changes classrooms on schedule and eats during the “assigned” lunch period. The two of them regularly interact with a group of younger children, around nine or ten years of age, who soon make it apparent that this story is a variant of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. It lacks sufficient characterization and explanation to make it a strong story. It was an odd choice to hold lead-off position in the issue.

Billie Sue Mosiman’s “The Long Lonely Empty Road” is about Ally McNeil, who has been lucky all her life — until now. Her car breaks down halfway to Las Vegas, where she is supposed to start a new job, and it’s “the first serious mishap in a life of happy non-events and years without lament.” One has led a charmed life indeed if a car malfunctioning is the first bad thing to ever happen to one, so we assume that there are going to be consequences that go beyond a mere dead car, even on a desert highway. Mosiman doesn’t disappoint us in this expectation, though she takes a roundabout way to get to Ally’s fate. The story is longer than it needs to be to tell the tale, detracting from its attempts to build suspense.

I’ve never been fond of excerpts from novels being published in magazines, but there must be strong audience demand for them, as the practice continues. This issue of Jamais Vu includes Chapter One of Brad Carter’s The Big Man of Barlow, entitled “How the Sasquatch Mourns His Dead.” Hank, the first person narrator leads off by telling us that he found Sasquatch around Christmas last year. His life-partner Gus is the one with the Bigfoot obsession, but in the way of couples that have been together for a long time, Hank humors Gus. Gus is dying, and the only way Hank really knows to fight it is to decorate their home with the most outlandish Christmas display possible, including having the wisemen don Arkansas Razorback hats that look like red plastic pigs and giving the angel Gabriel a ten-gallon cowboy hat, and setting up an entire croquet course in front of the manger beside a collection of mannequins that he acquired at a flea market, all topped off with a pink flamingo. It’s as offensive — and funny — as all get-out, and will probably drive the good Baptist who lives across the street into apoplexy, but it helps Hank with the depression of watching his partner die right before his eyes, full of pain. Carter has a nice colloquial style and a wild sense of humor, but it’s difficult to imagine where the novel goes after the end of this chapter — and I’m not inclined to find out.

In “Oldies” by Jack Ketchum, Helen, the first person narrator, tells us about her life with Maddy. One has to figure out the relationship between these two from the context, but it appears that Helen and Maddy were once lovers, and that Maddy visits Helen in a care facility in Helen’s old age. Helen appears to be suffering from dementia, and through the narration of her tale Ketchum delineates the confusion, loneliness and homesickness that result from her decline. It’s one of the best stories in this issue.

“Functionality” by Lucy A. Snyder is about Mark, a soldier, who has just been so grievously wounded that he is going to lose both his legs — unless he goes with “the project,” a shot that will save his legs but require him to be a soldier for the rest of his life. Mark chooses the project. The next thing he knows, he’s in Germany, and a doctor is telling him that he’s been there for six weeks and seen her every day. His memory has been affected by the nanites the shot released into his system. The good news is that his family has agreed to try to fix the memory problem; all he needs to do is sign off on it himself. And that’s when his problems really begin. It’s a short, sharp story that, without being in the least preachy, puts one in mind of the problems being faced by our veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan — not just the post-traumatic stress disorder, but the horrible brain injuries with which so many of them are living.

“Karmic Interventions” by William D. Carl is narrated by a man in a bar, a guy who talks too much when he drinks. See, he’s a romantic, but he’s been peculiarly unlucky in love — right up until he meets Suzie, who has had significant bad luck of her own. It’s love at first sight, until the narrator decides he doesn’t want to take chances on Suzie’s bad luck catching up to him. It’s a funny story.

“Inevitable as the Incoming Tide” by Rose Blackthorn is a poem with some lovely imagery, but ultimately it reads like something written by a moody teenage girl pining after a boy. “Ink” by Michael Bailey is another poem that seems to be by a depressed teen, this one apparently a suicide. “The Compassion of Erebus” by Vincenzo Bilof completely eluded me; I have no idea what the poet was trying to say.

The nonfiction is as plentiful as in the last issue. “The Art, Mystery, and Madness of Lydia Burris” is a gallery of Burris’s mixed media art; Burris is the artist for the covers of the first four issue of Jamais Vu. “Velocirapture: The Rise of Monster Porn” by Alexandra Christian, discusses the recent trend in erotic paranormal romance for matings between humans and different sorts of monsters, from werewolves to dinosaurs to Bigfoot. These works are usually self-published on Amazon and average 5,000 to 6,000 words, and the author doesn’t seem to think much of them — though she notes that they are sufficiently successful to offset student loans and mortgage payments in more than a few instances. Christian doesn’t much care to see her own efforts marketed alongside the anything-for-a-buck hard-core porn that has been showing up lately. “Scary and the Hendersons” by Jessica Dwyer is a discussion between Dwyer and Bobcat Goldthwait about obscure horror films. Lucy A. Snyder writes about “Meeting Chuck Palahniuk” at the Bram Stoker Awards convention in Burbank several years ago. Eric Beebe has a column on strange movies, like the infamous “A Boy and His Dog,” based on a Harlan Ellison story with the same title. William D. Carl has a second movie column, this one a review of the 1965 movie “Who Killed Teddy Bear?” James Newman reviews “We Are What We Are,” a 2013 remake of a Spanish film of the same name. Paul Anderson reviews Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, and Donald Jacob Uitvlugt reviews Brom’s Krampus the Yule Lord. Harlan Ellison writes that “guys are pigs,” though he allows that not all guys are pigs, and definitely not him — but most of them are (he explains that “pigs” is a shorthand for unclean, untidy, unsanitary and a few similar adjectives). The magazine closes with Paul Anderson’s fairly standard interview of Jonathan Maberry.

“Functionality” reminds me of something the director of our Veterans Services Office told me once about traumatic brain injuries; so many soldiers come home with them because field medicine is better now than it’s ever been. Soldiers with these injuries didn’t make it home from WWI/II, Korea or Viet Nam because they died in the field. So things are better… and there are unintended consequences.