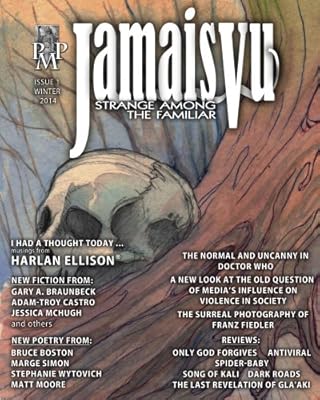

New magazines fascinate me. These days they seem to be popping up on the internet like mushrooms after a summer rain. Jamais Vu: The Journal of Strange Among the Familiar is the latest of these ventures to cross my desk. The first issue, dated Winter 2014, opens with a message from the Editor-in-Chief, Paul Anderson (the one who makes the content decisions, as opposed to the Executive Editor, Eric S. Beebe, who bills himself as a figurehead who pays the bills). Anderson explains that Jamais Vu is an experiment arising from Post Mortem’s start as a publisher of anthologies. Rather than continuing with anthologies, which don’t sell particularly well, or resorting to the $.99 digital “short” that’s all the rage on Amazon these days, Post Mortem decided to try a magazine. If the quality of the magazine consistently matches that of the first issue, this venture ought to be a success.

New magazines fascinate me. These days they seem to be popping up on the internet like mushrooms after a summer rain. Jamais Vu: The Journal of Strange Among the Familiar is the latest of these ventures to cross my desk. The first issue, dated Winter 2014, opens with a message from the Editor-in-Chief, Paul Anderson (the one who makes the content decisions, as opposed to the Executive Editor, Eric S. Beebe, who bills himself as a figurehead who pays the bills). Anderson explains that Jamais Vu is an experiment arising from Post Mortem’s start as a publisher of anthologies. Rather than continuing with anthologies, which don’t sell particularly well, or resorting to the $.99 digital “short” that’s all the rage on Amazon these days, Post Mortem decided to try a magazine. If the quality of the magazine consistently matches that of the first issue, this venture ought to be a success.

The first story, “Photo Captions” by Gary A. Braunbeck, gives us a first-person narrator who is looking through photos of his life with his wife, Laurie, beginning with their wedding. She never looked that happy again, the narrator muses, and the dread begins to gather. This woman just doesn’t have any luck, what with an early miscarriage, no honeymoon because of the death of her father, and on and on. And neither do Jeremy, our narrator, or his friends; there’s always some calamity. So Jeremy comes up with a plan. It’s a story that finds the horror in the everyday, written so matter-of-factly that you almost miss the way it sneaks up on you. Braunbeck is a strong writer who has used his gifts well here.

Michael Kelly’s “Bait” tells of a thirteen-year-old whose mother has gone missing and whose father dies shortly after his wife leaves. The teenager, who narrates the story, goes to live with his Uncle Ivar after his father’s funeral. In Uncle Ivar’s home there’s a cellar of some sort that’s guarded by a locked metal door. It’s a workshop, Uncle Ivar tells his nephew after a significant pause; it’s not safe to go in there. The door fascinates the boy, who can’t stay away from it. Uncle Ivar never lets him in, but it’s where he goes to get meat to cook for them. Of course, as must happen in such a story, the boy gets his hands on the key to the cellar door. Kelly does a fine job of leaving much for the reader to discern from an incomplete picture, just as the boy must figure out what’s going on.

The first sentence of Jessica McHugh’s “Another Pleasant Valley Sunday” caught my attention: “The car smells like failure, which smells like French fries.” To me, French fries always smell like success! But when you work at a fast food job, like Jimmy does, the smell loses its appeal. Jimmy just wants to get away from work, from his wife, Cynthia, from their kid, from everything, “to a place where no one knows the weak man he’s become.” Following his GPS to a random bar he’s chosen as his destination, he winds up in a small town off a dirt road with a stalled-out car, and stops in at a local bed and breakfast. Things start to get very strange then. However, the resemblance to the story and Twilight Zone script “It’s a Good Life” by Jerome Bixby diminished its impact for me.

In “Video Nasties” by Max Booth III, we’re grossed out by what a child sees on his television set — horror films so ugly and violent that it doesn’t seem even adults should be viewing them. After this mercifully short introductory passage (we get further scenes every now and then as the narrative continues), we’re introduced to eleven-year-olds Jeremy and Eddie, boys who hate their town and everyone in it. Out of boredom and hatred, Jeremy comes up with a plan to “have some fun.” Soon the boys have visited their local mall and kidnapped a two-year-old child, which they march to their Secret Spot in the woods. The story is based on an actual event, and it is truly horrifying in every sense of the word. This one might remind you of “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” by Harlan Ellison, which was similarly based on the real-life murder of Kitty Genovese.

In “Shiva,” the author, Cameron Suey, brings Ronen home from a continent away for his brother Lev’s funeral. Ronen refuses to sit shiva with the minyan for his brother, despite his father’s glares. But Ronen has his own form of shiva: Lev appears to him, briefly but often. Lev doesn’t know where he is, and has begun doubting the existence of God — so much so that Ronen concludes that Lev’s ghost is just an aspect of his own conscience, a wish-fulfillment fantasy. It’s a surprisingly philosophical story to find in a horror magazine.

Schizophrenia is the villain of “The Hydra Wife” by Sandra M. Odell. Victor imagines himself as a knight in shining armor when his wife, Anya, is diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder, which he envisions as a hydra. Caring for her quickly becomes almost more than he can bear, especially on top of the demands of his job. And his fantasy of his wife as a hydra seems to take on a reality as the days go by and other women start to tempt him almost beyond his capacity to resist. It’s a heart-wrenching story, delicately told.

I’ve become one of Adam-Troy Castro’s biggest fans over the last few years of reading short fiction, and “Another Friendly Day in the Antique Trade,” while slight and humorous instead of the usual deep and thought-provoking, reinforces my fandom. See, there’s a mouth in the streets and sidewalks that eats residents of Fayette every now and then. The morning of the story, the mouth is right in front of the narrator’s antiques store, so that the narrator sees Otis gets eaten. It’s a nice set-up for a story about the customers who arrive next, new in town after surviving a series of unfortunate events. The story made me laugh out loud..

The poetry is less successful than the narrative fiction. “Eventually, You Become Immune” by Stephanie M. Wytovich is about a suicide and her surviving ghost. The horror is so muted as to be absent, and I found the imagery of herbs as bodies a poor metaphor. “Procrastination’s Joy” by Matt Moore is a short dialogue between Death and Dreaming that scolds those of us who want to get something done but never seem to get to it — a sermon in seven lines that does not cut deeply enough. Marge Simon’s “The Moors” is about a human sacrifice, but feels incomplete and does not shock as much as the poet intended, mostly because it has been told too many times. As is so often the case, Bruce Boston’s poem is the best of the lot: “The Crossing Guard” is a subtle poem about patience, and our society’s lack of it.

There is a lot of nonfiction in this issue, from reviews of books and films (including of books that are no longer new; to my mind, a good idea, bringing excellent older fiction to a new audience), to an unattributed piece on a forest where many Japanese commit hara-kiri, to a discussion of Doctor Who and particularly regarding the fact that most of Doctor Who’s adventures take place on Earth, to a pair of essays about media’s influence on violence in society, to a column by Harlan Ellison about his meeting with Whitey Bulger. In fact, the nonfiction is at least as extensive by page count as the fiction and poetry. It’s generally well-written and informative. The review of Dan Simmons‘s Song of Kali, an excellent novel that many contemporary readers may have missed, was especially useful.

The e-book version of this first issue costs a mere $2.99. It’s worth the minor investment. I’m looking forward to watching the magazine develop over the next several issues.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks