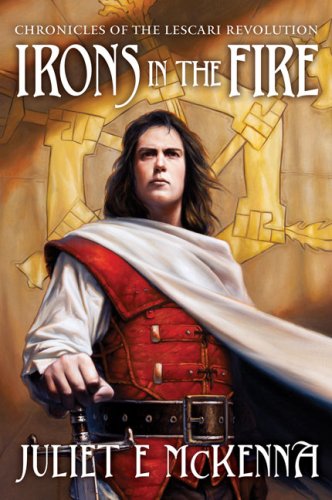

Irons in the Fire by Juliet E. McKenna

Irons in the Fire by Juliet E. McKenna

Contemporary wisdom holds that a fantasy novel should include the following non-exclusive elements and that they, or at least tantalizing glimpses of them, should be apparent from the beginning:

- distinctive characters whom the reader can like, relate to,or watch with concerned or morbid fascination

- a fascinating world

- a conflict, crisis, or unrealized desire that meaningfullyimpacts said characters and world

Ideally, a brisk (or at least smooth) pace and clean, crisp prose combine with these elements to create a lucid, vivid, captivating dream that, as is commonly stated, “sucks the reader in.”

Unfortunately, I found the latest tale of Juliet McKenna’s signature world of Einarinn, Irons in the Fire, lacking in each of these elements, and in light of this and the number of other books on my reading list, I decided to move on without finishing it.

Irons in the Fire is one of the most slowly developing fantasy books I can recall. It opens, of all things, with a gravedust-dry excerpt from a scholarly political almanac that purports to inform the reader — duchy by duchy — of the statuses of the six conflicting duchies in the country of Lescar. (The plot focuses on a handful of characters hoping to end the perpetual stalemate that, reportedly, is causing the people of Lescar to suffer.) The story then shifts to the foreign city of Vanam and the scholar/clerk Tathrin, a young Lescari exile who aspires to be one of these revolutionaries. But Tathrin, who is the main character in 14 of the book’s 38 chapters, is simply a bland fantasy-youth stereotype, and neither he nor the generic medieval flavor of the world provide any spark to enliven the opening chapters, which can be summarized like this:

- Tathrin has a flashback and then goes with his new boss to a gathering for Lescari exiles.

- Tathrin listens to an info-dumping talk between his boss and other merchants, which is interrupted by a patriotic elder.

- In Lescar, someone named Karn watches mercenaries take over a bridge.

- Tathrin talks with a friend (more info-dumping), gets his father’s mercantile weights certified, and goes to see the patriotic elder.

- Aremil (Tathrin’s friend and a crippled exile with noble blood) meets the patriotic elder (more info-dumping) and talks with Tathrin.

- Tathrin is visited by the patriotic elder (more info-dumping about Tathrin and Aremil), who takes Tathrin to meet two other potential revolutionaries. Tathrin buys a map book and thinks.

- In Lescar, the Duchess Litasse attends a meeting with her duke-husband, his spymaster, and Karn (more info-dumping). After Karn and the duke leave, she gets cuddly with the spymaster … but they still keep talking a little longer.

Seven chapters of unremarkable introductions and set-up, by way of often stilted conversations that include a numbing amount of information about politics and commerce. (And no viewpoint characters “on the ground” in Lescar to make the dukes’ conflicts visceral or meaningful.) Clearly, the world is detailed, but at least in the beginning, the details drag the plot to a virtual standstill. (And the conspiring revolutionaries plot can be done well — magnificently, even, as demonstrated by Guy Gavriel Kay‘s Tigana.) The unremarkable characters failed to hold my interest, and the writing is adequate but undermined by semi-archaic language and clichés (e.g. “no longer feeling as if she were walking on eggshells, p. 152).

Hard-core fans of medieval fantasy may wish to give this one a passing glance, and perhaps someone will find that the novel accelerates to an amazing conclusion. If so, please submit a guest review here so that others will have a second opinion.

Chronicles of the Lescari Revolution — (2009) Publisher: The country of Lescar was carved out of the collapsing Tormalin Empire by ambitious men who all felt entitled to seize power for themselves. Now six rival dukedoms are ruled by their descendants, who all lay claim to the crown of high king. Dukes pursue their ambitions through strategic alliances and strength of arms while their duchesses plot marriages and discreet pacts. As long as the battles stay inside Lescari borders, neighbouring powers are content to buy up whatever the dukedoms can produce and sell their rulers whatever they can afford by way of luxuries or necessities. Amoral opportunists come from far and wide to seek their fortunes in the mercenary bands who ride the successive tides of warfare. All the while the ordinary people struggle to raise their crops and families amid the turns and chances of uncaring uncertainty. Many leave, preferring to live abroad as exiles, poorer but safer. Those who can afford to send whatever coin they can spare back to family and friends still labouring to pay the dues and levies that the dukes demand. Now a mismatched band of exiles and rebels are agreed that the time has come for change. Can a small group, however determined, put an end to generations of intractable misery? Perhaps. After all, a few stones falling in the right place can set a landslide in motion. But who can predict what the consequences will be, when all the dust has settled?

Agree! And a perfect ending, too.

I may be embarrassing myself by repeating something I already posted here, but Thomas Pynchon has a new novel scheduled…

[…] Tales (Fantasy Literature): John Martin Leahy was born in Washington State in 1886 and, during his five-year career as…

so you're saying I should read it? :)

As a native New Yorker, I love the idea of the city being filled with canals and no skyscrapers! And…