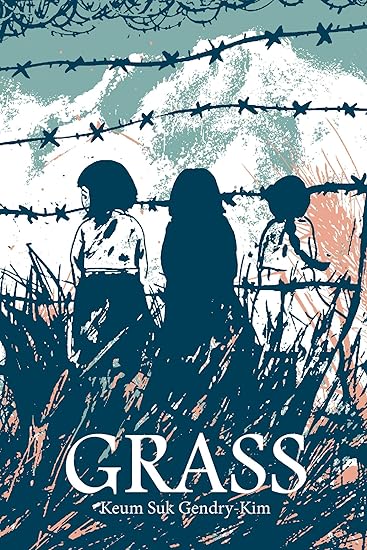

![]() Grass by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim (writer and artist) and Janet Hong (translator)

Grass by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim (writer and artist) and Janet Hong (translator)

Trigger Warning: This review discusses harsh content, including descriptions of murder, rape, and suicidal thoughts, that are a part of Okseon Lee’s true biography.

Grass, by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim and translated by Janet Hong, is a powerful story about World War Two, and the Korean women who were taken from their homes, often as little girls, and sold into sexual slavery for Japanese soldiers. This biographical work is about Okseon Lee, who was interviewed extensively as an older woman by the author. It is a disturbing tale to read, but it is a story that needs to be told. Gendry-Kim does an excellent job relating the events in Lee’s life.

Gendry-Kim tells this story by including herself in the book. We see scenes of her visiting Okseon Lee, Granny Lee Ok-Sun, to get her life story directly from her. Granny Lee is hesitant to give details at times, but the author is patient, and at times quite insistent, that Lee tell her more about each event. These scenes of author and the subject of the biography are interspersed throughout the long book (about 450 pages), and those moments seem just as important in our getting to know Lee as are her relating the events that unfolded in her young, formative years.

Lee claims to have never had a happy moment since she was born, and this story seems to support that claim for the most part. As a little girl, Okseon Lee wanted more than anything to go to school, and we get a picture of a young, innocent free spirit unhappy even with her childhood, because of the harsh circumstances of her upbringing. Her unhappiness is in large part due to the lack of food and her family’s need for her to watch after her younger siblings. She worked hard around the house from a young age, and hard work and near-starvation seemed to be her lot in life. She told of eating bark from trees to try to fill her belly. And her father complained of how bad things had gotten when he said, “The landlords may have taken all our crops, but the Japanese bastards are worse.” However, it would get only worse from there for young Lee.

While we get told of events unfolding in Korea and China as the invading Japanese capture Beijing and we learn about the six-week-long Nanjing Massacre of around 300,000 people, the book focuses on Lee’s personal tale: Lee is told by her mother that she will be adopted by childless couple who are owners of an udon shop in Busan, and when Lee also is told that the couple will send her to school, she gets excited about leaving her family behind. She quickly finds out that the couple really wants someone to do slave labor in and around the shop. Granny Lee tells the author that the only education she got was when she went to Homi University. A homi is a hand hoe, a tool that she would have used in her work. Granny Lee laughs as she tells this joke, but the joke is not really very funny considering how her hopes were crushed as a young child who wanted only to learn and become educated.

The owners eventually sold Lee to a couple who ran a tavern, and the pattern was repeated: Lots of work and no education. She is still near starving, and she is so hungry, she steals an egg. But she never gets to eat it, and she is beaten for her behavior when she is found out. And when she is sent out on an errand, she is abducted by two Korean men who sold her into sexual slavery. She is put in a freight train compartment with no windows, and locked in with other girls who had found themselves also abducted, sold, or tricked into becoming “comfort women” for the Japanese soldiers. They had nothing to eat, and some of them were as young as thirteen-years-old. The Japanese soldiers who ran the train took them across the Tumen River and into China. And from there, life got only worse.

After relating the story of being put in a labor camp, Lee tells the author of her being forced to become a comfort woman, a sexual slave, and tells of the horror of her first rape by soldiers: “I was raped,” Lee says frankly, “Like an animal.” The artist drives home this horror by presenting us with multiple pages of six black panels. Then Lee says, “I felt so dirty. That’s why so many girls try to kill themselves after rape. I wanted to die. But I couldn’t kill myself. No matter how much I wanted to, there was no way to do it. I was alive, but I wasn’t living.” The artists shows us close-ups of Lee’s face and hands as she talks to us.

Other indignities and horrors awaited. She thought she was dying when she got her first period, because nobody had ever told her about it. She had only another young girl to help her figure out what to do and how to take care of herself. The food continued to be bad, practically rotten, and they were near starvation. They were given horrible weekly medical exams for venereal disease at the military hospital. Lee, not surprisingly, got syphilis. Her “treatment” included a procedure that prevented her from ever having kids: “I got better eventually, but because of that, I could never have any children.”

Lee was at multiple comfort stations, and she speaks directly, and without evasion, about her treatment. It is a difficult book to read, and yet it is important for this story to be told. This history of women who suffered during WWII as sexual slaves drives home the multiple horrors of war that happen outside of direct warfare. The stark black-and-white artwork is haunting and effective at conveying the harshness of Lee’s life. I have read it twice now, and I am glad that it was written as a graphic novel. Telling Lee’s story visually makes it all the more compelling. Yes, it reveals the darkest parts of human nature, but it also serves as a warning: Grass is as strong an anti-war book as I have ever read.

Sounds like a powerfully disturbing but important book