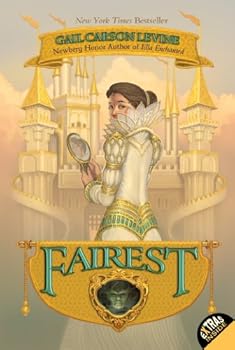

Just as Gail Carson Levine‘s award-winning Ella Enchanted tackled the story of Cinderella, giving the story depth and meaning whilst simultaneously treating the reader to one of the best heroines and most realistic romances in all of Young Adult literature, Fairest purports to retell the fairytale of Snow White with a few twists.

Aza was abandoned as an infant at the Featherbed Inn and adopted by the innkeeper and his wife. Though loved by her family, Aza is ashamed of her weight and perceived ugliness, particularly since the kingdom of Ayortha is one that prizes beauty and song above all other virtues. Shunned by many of the guests, Aza enjoys solitude and occasionally the company of the gnomes that sometimes stay at the inn, including one that prophesies that in the future they’ll meet again underground at a time when Aza will be in grave danger.

A change in the routine of Aza’s life comes when a noblewoman in need of a lady’s maid convinces her to attend the marriage of King Oscaro and his young commoner wife Ivi. Through a sequence of events, Aza finds herself in way over her head when she’s made lady-in-waiting to the new Queen Ivi, who wants to exploit her talent of throwing her voice (what Aza calls “illusing”) in order to make it appear as though she herself is a gifted singer.

What follows is a fairly loose retelling of “Snow White,” with several good ideas on adapting fairytale to fit Aza’s personal story, including a more sympathetic wicked queen, a unique interpretation of the magic mirror, gnomes in place of the seven dwarfs, and even a funny twist on the poisoned apple (it turns out Aza doesn’t like apples all that much). When Aza’s vocal deception is revealed, she must clear her name, secure the safety of the kingdom, and reunite with her love, Prince Ijori.

What follows is a fairly loose retelling of “Snow White,” with several good ideas on adapting fairytale to fit Aza’s personal story, including a more sympathetic wicked queen, a unique interpretation of the magic mirror, gnomes in place of the seven dwarfs, and even a funny twist on the poisoned apple (it turns out Aza doesn’t like apples all that much). When Aza’s vocal deception is revealed, she must clear her name, secure the safety of the kingdom, and reunite with her love, Prince Ijori.

Fairest is clearly meant to provide commentary on our appearance-obsessed society, but unfortunately the issue is not handled particularly well. Levine spends more time on how Aza simply wants to be pretty, rather than the pain of the hurtful comments that are directed at her and the psychological effect such things have on a young mind. There’s a difference between being self-conscious about one’s looks and excessive worrying about one’s looks (generally described as “vanity.”) Aza falls into the latter category, as she’s constantly looking into mirrors to check her reflection, worrying about her clothing, and has formed the habit of putting her hand over her face so that people can’t see her. Wouldn’t this just attract more attention to herself? (The moral is also somewhat undermined when she is spared by the “huntsman” ordered to kill her because he finds her so beautiful, thanks to a magic potion she took earlier. So… beauty really is important. Without it, she’d be dead.)

The importance placed on beauty in Ayortha also creates problems further on in the story. We’re supposed to be concerned when Ivi takes over the palace and begins to meddle with the way things are run, but we’re never really given a reason to care about the wellbeing of Ayortha. Apparently it’s full of people who ostracize Aza just because she doesn’t fit into the social norms, as according to her: “As bad as the ones who stared were the ones who looked away in embarrassment. Some guests didn’t want me to serve their food, and some didn’t want me to clean their rooms.” If this is the way Ayorthians treat “ugly” children, then their kingdom can get invaded by Huns and burnt to the ground for all I care.

Perhaps it’s unfair to hold up Fairest against Ella Enchanted, but really, the comparison is inevitable when one considers the differences between the two heroines. Ella burst off the page with liveliness, good humor and zest for adventure, whereas Aza is significantly more sedate and less confident. Nothing wrong with that of course, but Aza turns out to be one of those girls that will just Not. Stop. Crying. She cries when she’s happy. She cries when she’s sad. She cries when she’s embarrassed, or frightened, or nervous. At a crucial point of the story, when she should be (and when her counterpart Ella certainly would be) looking around for weapons or an escape, she simply sits and cries some more. I’m afraid I got fed up with her well before her happily ever after rolls around (did she cry for that too?).

Fairest is set in the same universe as Ella Enchanted, and as such there are several fun references to the earlier book. Aza is the little sister of Areida, who was Ella’s best friend at finishing school, and there are mentions of Ella, her father Sir Peter, and Lucinda the fairy (who is behind most of the trouble in this book too!). But unlike the previous book, which shed light on several fantasy idioms and poked gentle fun at the clichés of a fairytale realm, there are several awkward or unwieldy plot devices here that come across as unintentionally funny.

For instance, Ayortha is a singing kingdom, which means that its people “sing” their declarations of love to each other, get together for communal sing-a-longs, and even (as in Aza’s case) sing when they’re in mortal peril. Sure, it’s all in keeping with their culture, but on trying to picture it in your mind, it just seems silly. In another example, King Oscaro is hit on the head with an iron ring and for some reason loses the ability to speak (I’m guessing he’s concussed, but wouldn’t it have just been easier to say he’d had a stroke?), and later Aza bites into the infamous apple, chokes on her mouthful and…goes into a coma? Say what? The book is full of awkward, strange plot contrivances like these (such as Aza trying to squeeze through a window instead of looking for a door, Aza “grinning” at a man who’s just tried to kill her, and a kiss/declaration of love that is abruptly cut short by the couple simply walking away from each other for no apparent reason) that grate on the imagination and make it difficult to really “believe” in what’s going on.

Perhaps I’m being too harsh. Like all of Levine’s books, Fairest is told in a bright, breezy, eminently readable tone and is certainly entertaining while it lasts. Despite her cry-baby tendencies, Aza’s first-person account of her life is sincere and sympathetic, and the world that Levine has created for her characters is just as colourful and charming as it was in Ella. But I know Levine can do better than this. I adored Ella Enchanted, and recommend it to anyone who cares to listen to me, but this follow-up book pales in comparison. Aza is a bit too dim-witted for her own good, and the reason I haven’t mentioned much about her romance with Prince Ijari is simply because there isn’t all that much to say. I laughed and cried alongside Ella, but all I wanted to do while reading Fairest was hand Aza a tissue and tell her to stop her endless moping.

Fairest by Gail Carson Levine

Fairest by Gail Carson Levine

Actually, Areida is the younger one, not Aza. ;)

Ella Enchanted was very good but honestly, Ella’s snippiness, ingratitude to Mandy (who would have fought the world for her), and immature need to *constantly* rebel got on my nerves probably as much as Aza’s tears got on yours. As a sensitive person myself, I found Aza far easier to sympathize with and easier to digest as a character. I also don’t see what’s so bad about worrying that she’s pretty. That’s what young women conditioned by a shallow society typically feel they should do.

Good review, though.

When I closed the book I was disappointed, too. I was full of excitement because Ella-enchanted is a book that I enjoyed SO much. I had no emotion in finishing the book. Maybe I was expecting too much, but still…