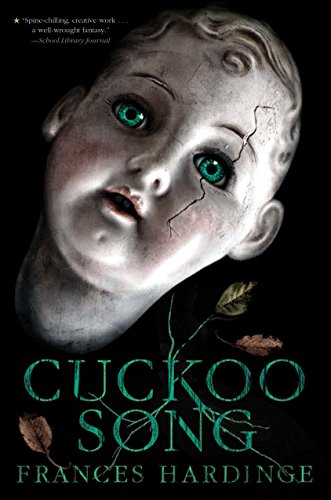

![]() Cuckoo Song by Frances Hardinge

Cuckoo Song by Frances Hardinge

As usual, I am late to the party. Published in 2014, Cuckoo Song is Frances Hardinge’s sixth novel. Her debut novel, Fly by Night, won the Branford Boase First Novel Award and her 2015 novel The Lie Tree won the Costa Book Award, (the first children’s book to do so since Philip Pullman‘s The Amber Spyglass

, which is saying something). I had no experience of Hardinge’s work and, without the knowledge above, no real expectations. The result was an extremely pleasant, if slightly bizarre, surprise. So, late I might be, but I’m thrilled to have gotten here.

A plot summary of Cuckoo Song is a challenge. It would be a crying shame to give too much away because the joy of the book lies in the myriad mysteries that take off on page one and gambol along until the finale. Hardinge layers mystery upon mystery, sometimes divulging at unexpected moments, only to raise more questions. It makes for a compelling read.

In simple terms then, the story centres on a young girl named Triss who wakes one day after a bad accident to find things chillingly different from how they were before. Mollycoddled all her life, Triss is used to being bed-bound and told she is unwell, but now her symptoms are much more peculiar. It starts when Triss’ doll opens its eyes and demands to know, in hostile terms, who Triss is and what she is doing there. (The horror story that most upset me in my youth involved a murderous doll climbing up the stairs to kill me, and so this touched a nerve.) Then there is Triss’ insatiable appetite which sees her go to frightening lengths for food (edible or not). What’s more, Triss keeps waking to find dead leaves around her head and her little sister Pen looks at her with ill-disguised malice.

Triss’ mission to uncover these mysteries leads her into a world of twisted and dangerous magic that runs its course right under the noses of her hometown’s inhabitants. At the heart of this world lies the Architect, an evil wielder of immense power who, for reasons I won’t divulge, wants to punish Triss’ family.

Hardgine’s weirdness is a huge asset. This is a story that not many people could dream up and most won’t see coming. I’m not giving away too much to say that when Triss first opens her mouth wide enough to consume an entire doll as it screams in protest, I did a double take. My mind reassessed the situation. So this is a story where little girls eat their dolls, I thought. Not the safe adolescent tale I had anticipated.

The psychological impact of Triss’ condition is also intelligently explored. As she tries to work out what is happening, Triss is forced to consider the possibility that she is going insane. Her barely contained panic that her parents will cart her away to an asylum feels very real and very frightening. I had enormous sympathy for her. But more than that, I just wanted to know what was going on — and that’s the mark of a killer plot.

As bits and bobs are revealed the reader becomes more familiar with the magical world, which is interesting for its unusualness. We meet peculiar, shadowy beings who can’t be near scissors and for whom church bells spell disaster. Why? You’ll have to find out.

The pace is perfectly devised. The mystery slowly creeps out until the halfway mark when the adventure bursts into action and never lets up. As for characterisation, a few of the lesser characters are disappointing, but both Triss and her sister Pen are complex and contradictory. Pen, in particular, who starts out as the typical, brattish younger sister, grows throughout the story to fulfil a much more important role. She surpasses the two dimensional tool that she might have been in the hands of a lesser writer.

Cuckoo Song is a huge story. Beneath the central premise lie so many other facets. Stories about the first world war, about grief and loss, about parenthood and sisterly dynamics all vie for attention. The result is a rich and intriguing story; a mystery, fantasy and historical fiction all muddled together. One thing’s for sure, I will certainly be reading more of Frances Hardinge.

~Katie Burton

![]() Most people are familiar with stories of changelings; the fairy babies that replace mortal infants in the crib so that parents don’t suspect their real child has been stolen away. As you might reasonably predict from the book’s title, the story of Cuckoo Song revolves around changelings, though author Frances Hardinge goes about telling it from an unexpected point-of-view.

Most people are familiar with stories of changelings; the fairy babies that replace mortal infants in the crib so that parents don’t suspect their real child has been stolen away. As you might reasonably predict from the book’s title, the story of Cuckoo Song revolves around changelings, though author Frances Hardinge goes about telling it from an unexpected point-of-view.

Theresa Crescent (or “Triss”) wakes up after a half-remembered accident, disoriented and afraid. Though her memories and surroundings gradually return to her, she can’t shake the feeling that something is very wrong. Her younger sister Pen seems to hate and fear her, and her parents are almost suffocating in their over-attentiveness. She has an insatiable appetite, she wakes up with leaves in her hair, and some of her belongings are missing.

Mysteries pile up: strange letters arrive at the house, whispered conversations are heard between her parents, and Pen’s animosity reaches new heights as she inexplicably accuses Triss of “doing everything just a little bit wrong”. Triss is desperate to solve the mystery of her own life, especially as she can’t shake the feelings that — somehow, for some reason — she’s running out of time.

Cuckoo Song is a fairy tale at heart, but one beating in the body of a mystery, with multiple veins of the class divide, familial strife, post-war upheaval and questions of identity, belonging and mortality. Most interesting of all, however, is the mood of psychological horror that grips the first half of the book. In all, it’s quite a dish.

Taking place in the wake of World War I, Hardinge vividly sets the scene when it comes to describing gaslights, fashion, motorcycles, even the recent popularity of Egyptology and jazz, but is also touches on themes prevalent at the time: women’s emancipation, abject poverty, shell-shocked soldiers, the atmosphere of change in the air.

Yet she’s most interested in the “cuckoo” of the book’s title, and its understanding of its place in the world. As I’m sure you learnt in school, a cuckoo lays its egg in another bird’s nest, forcing it to hatch and rear the baby cuckoo, often neglecting its own offspring in the process. It’s a neat analogy for a changeling child, and I’m sure it won’t come as too much of a surprise to learn that Triss is this cuckoo.

Triss has to cope with a claustrophobically unbearable situation in which she’s acutely aware of her parents’ close eyes upon her, and desperate to live up to their expectations of her. She must be healthy, she must be happy, she must be obedient — or else they might recognize her as the cuckoo and reject her. The supernatural quality of the tale plays out alongside the all-too-real anxiety that exists within a dysfunctional household laden with secrets.

The Crescent family is a striking portrayal of a family so mired in tragedy, worry and mistrust that communication is impossible. With a son lost in the war, Mr and Mrs Crescent end up coddling one remaining child and scapegoating the other, creating the suffocating atmosphere that Triss (or Not-Triss) must navigate.

Supporting characters in Cuckoo Song are good too, such as Violet, the fiancée of the Crescents’ lost son Sebastian, a young woman who refuses to bow to social mores, and Pen, the Crescents’ youngest daughter who is all spikes and suspicion — at least until she starts spilling her secrets.

As Triss gets closer to the truth, Hardinge doesn’t let her twisty plot spiral out of control: she sows clues and hints throughout the course of the story, gradually teasing them out as they move toward their reveals. She’s also wonderful at descriptive prose. A motorbike, for example: “there was something bold and ugly about the way it let you see right into its metal works. It had the rough cockiness of a stray dog one hair’s breadth away from snarling.” Or a stranger’s smile: “There was a kink at the corner of his smile that made [Triss] think of a treacherous raised nail on a stair carpet.”

This is a story that could have easily been told from a number of points-of-view: Pen’s, perhaps, or Violet’s or Mr Crescent’s. But Hardinge chooses Triss to tell this story, and the character’s experience is a harrowing one, involving an identity crisis, physical attacks and the constant thought of impending death. Using the 1920s as a backdrop to the dark side of fairy tales is a combination that works surprisingly well, and Hardinge is careful to make sure every character — even the uncanny ones or the those that pose a direct threat to Triss — have understandable motivations and perspectives.

Cuckoo Song is the first book I’ve read by Frances Hardinge, and I was excited to discover she has plenty more work published. I’ll be checking out her back-catalogue sooner rather than later.

~Rebecca Fisher

Don’t feel bad about being late to the party–I’ve wanted to read this for a long while and still haven’t gotten around to it. I’m glad you liked it, though! :)