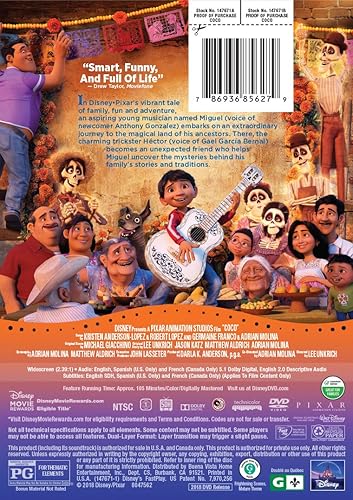

![]() Coco by Lee Unkrich & Adrian Molina

Coco by Lee Unkrich & Adrian Molina

When you settle down to watch a Pixar movie, you know you’re in for a treat. But as it happens, I finished Coco with rather mixed feelings. It ticked all the boxes of what we’ve come to expect from Pixar: a fascinating and inventive original premise, loveable characters, plenty of humour, at least one surprising plot-twist, and visuals that seem to glow with colour (especially in this film!) And yet Coco treads a lot of familiar ground when it’s compared not only to other the rest of the Pixar repertoire, but a wider range of animated family films.

When you settle down to watch a Pixar movie, you know you’re in for a treat. But as it happens, I finished Coco with rather mixed feelings. It ticked all the boxes of what we’ve come to expect from Pixar: a fascinating and inventive original premise, loveable characters, plenty of humour, at least one surprising plot-twist, and visuals that seem to glow with colour (especially in this film!) And yet Coco treads a lot of familiar ground when it’s compared not only to other the rest of the Pixar repertoire, but a wider range of animated family films.

Miguel Rivera (Anthony Gonzalez) is a twelve-year old boy with music in his soul. He’s desperate to become a musician and to follow in the footsteps of his idol Ernesto de la Cruz (a famous actor/singer/song-writer) but due to a dark family secret, all music is strictly forbidden in his household.

Seeking inspiration from de la Cruz, Miguel makes plans to enter a talent show during the Día de Muertos celebration. But after sneaking into de la Cruz’s mausoleum to borrow his guitar, Miguel instead finds himself in the Land of the Dead, where his ancestors are temporarily passing over into the Land of the Living to visit their loved ones for the holiday. And if he wants to get back, he needs to find his great-great grandfather and find out exactly what happened that resulted in the banning of music from the Rivera home.

There’s a lot more to it than this; in fact, I was surprised at the complexity of the storyline. Plans keep changing, goal-posts keep shifting — there’s a lot going on in this film, with an array of characters to help or hinder (sometimes both!) Miguel in his quest to return home.

It’s by no means a bad movie — of course not, it’s Pixar! Even their worst offerings are 99% better than almost every other movie that’s released per year. But as I said earlier, Coco is also a movie that feels very familiar in a lot of ways. Consider this: a young man pursues his creative dream behind his family’s back, deriving inspiration from a deceased celebrity.

It’s by no means a bad movie — of course not, it’s Pixar! Even their worst offerings are 99% better than almost every other movie that’s released per year. But as I said earlier, Coco is also a movie that feels very familiar in a lot of ways. Consider this: a young man pursues his creative dream behind his family’s back, deriving inspiration from a deceased celebrity.

A fatal error of judgment separates him from his family and throws him into a dangerous new environment, where he forms an alliance with a misfit who promises him assistance in return for the young man’s help in the pursuit of his own personal goals. Finally, each one finds out a startling truth about their family history and outwits a villain attempting to steal his rightful legacy.

It’s the plot of Coco … but also the plot of Pixar’s own Ratatouille. Yes, the two films are more different than similar, but Coco also reminded me of The Corpse Bride and The Book of Life, two animated films dealing with journeys to the Land of the Dead, the latter of which also takes place during Día de Muertos.

Or how about this for a protagonist: a youngster has a passion or a calling that is vigorously opposed by their families, but who will eventually come around by the story’s end. This describes Miguel, but also Hiccup (How to Train Your Dragon), Moana (Moana), Merida (Brave), Eep (The Croods) and even Ariel (The Little Mermaid).

Oh, and what about the use of the Hidden Villain trope, in which a seemingly trustworthy and benign character ends up being dangerous and malicious? Frozen, Big Hero 6, Wreck-It Ralph, Zootopia — they’ve all used this ploy, and at this point I’d be surprised to watch a Disney film and discover that someone WASN’T secretly evil.

Perhaps I just watch too many movies, but I couldn’t help but feel a certain sense of déjà vu on watching Coco, one that ever-so-slightly sapped my enjoyment of it. Having undergone a “renaissance” of sorts in the quality of their films, Disney/Pixar are slowly but surely slipping into a formula that undermines the studio’s reputation for creativity and inventiveness.

I LOVED this movie!