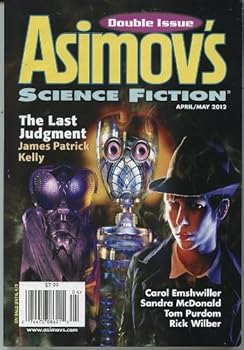

The April/May 2012 edition of Asimov’s Science Fiction is full of some of the best short fiction I’ve read in a while. The best story is a subtle novella by Rick Wilber called “Something Real.” It helps if you know a little bit about the baseball player and World War II spy named Moe Berg, an actual if little known historical figure who is brought vividly to life in this alternate world tale. The Moe Berg of this story is just as talented as the fellow who lived in our world, proficient in a number of languages and able to speak intelligently about cutting edge physics. Berg’s most important assignment, in life as well as in this story, was to attend a seminar Heisenberg gave in Switzerland in December 1944 and attempt to determine how close Germany was to building an atomic weapon. If Berg concluded Germany was close, he was to assassinate Heisenberg. This story is built around that particular encounter, and is as fascinating from a historical perspective as from a fictional perspective. Wilbur knows his subject well; Wibur’s touch is so sure that it is often hard to distinguish the fact from the fiction.

The April/May 2012 edition of Asimov’s Science Fiction is full of some of the best short fiction I’ve read in a while. The best story is a subtle novella by Rick Wilber called “Something Real.” It helps if you know a little bit about the baseball player and World War II spy named Moe Berg, an actual if little known historical figure who is brought vividly to life in this alternate world tale. The Moe Berg of this story is just as talented as the fellow who lived in our world, proficient in a number of languages and able to speak intelligently about cutting edge physics. Berg’s most important assignment, in life as well as in this story, was to attend a seminar Heisenberg gave in Switzerland in December 1944 and attempt to determine how close Germany was to building an atomic weapon. If Berg concluded Germany was close, he was to assassinate Heisenberg. This story is built around that particular encounter, and is as fascinating from a historical perspective as from a fictional perspective. Wilbur knows his subject well; Wibur’s touch is so sure that it is often hard to distinguish the fact from the fiction.

A close second in my affections, “Living in the Eighties” by David Ira Cleary, is a novella in which two music lovers discover a website that promises travel to either the past or the present; just pick your date. Clayton, a bassist, wants to travel to the future to find a cure for his diabetes before he loses his few remaining toes. The first-person narrator, Bob, wants to travel to 1986 — for the music, he says, but we learn soon enough that his real aim is to save the life of his then-girlfriend. The key to traveling in time turns out to be listening to really loud music while watching a flickering computer screen on the right website. There is much fun to be had in this story if you’re a lover of eighties music, as the references to genres, bands and individual pieces are numerous. Even if you could do without ever thinking about Sid Vicious again, though, this story of a world gradually changing the more Bob travels to the past is a nicely complex tale of regret and change.

The opening novella, “The Last Judgment” by James Patrick Kelly, is a detective story set in a world where aliens have eliminated all the men from Earth. The aftermath wasn’t what the aliens intended — an incredible outpouring of violence as women killed themselves and others in despair and anger. The aliens keep the species going by “seeding” the women without so much as a by-your-leave, and many women simply have themselves “scraped,” not wishing to bear a child under such circumstances. As the first person narrator, the private detective confronted with the mystery, says, the whole notion filled her with “stony rage.” The worst part of the aliens’ error, though, is their complete misunderstanding of gender roles in human society. Given the state of our medical science, one need not have a XX chromosome to be male. Indeed, the new society created by the aliens appears to be creating new men medically. This background comes to overwhelm the simple case of theft the detective is asked to solve, making this story a rich brew of sexual politics without any preaching. I was taken aback, however, by the implication toward the end of the story that women fulfilling leadership roles are necessarily more male than women fulfilling more nurturing roles. The story also seems to suggest that a human world without men would have to create them. Thus, Kelly seems to be having something of an argument with Joanna Russ, the author of the classic story, “When It Changed,” in which male settlers on a newly discovered planet are killed by a plague, while the women survive — and appear not to miss their male counterparts at all. I do not mean to imply that Kelly’s story is a pretext for arguing a premise; it’s a story, a good, sharp, provocative story. It provides plenty of fodder for speculation and discussion.

The best of the short stories is Tom Purdom’s “Bonding with Morry,” in which an elderly man who is beginning to have some trouble taking care of his needs on his own is pressed to accept a robot companion. Well, not actually a companion. In fact, Morry insists that his robot is a tool, not a housemate, and refuses to give it human features: it has wheels instead of legs, it does not have a simulated face, and Morry even names it “Clank.” Morry’s world isn’t happy with how he treats his robot, though; some call them “CyberAmericans” and argue that they are entitled to full rights. Years go by and Morry is more or less forced to make some physical changes to Clank, but his opinion of Clank’s essential character as a machine doesn’t change — or does it?

“Sexy Robot Mom” by Sandra McDonald is another robot story, this one about a robot who serves as a gestational chamber for babies. Alina is on her fourteenth pregnancy when she abruptly goes into stasis, presumably because of some ecological disaster. When she is awakened fifty years later, her part of the world has fallen into a deep freeze because of global climate change, and her rescuer tells her that the parents of the fetus she carries are dead. But Alina’s directive cannot be overridden, and she insists on setting off for Georgia regardless of the wishes of her rescuer. The story is not entirely successful, but it makes a nice complement to “Bonding with Morry.”

Gray Rinehart explores mechanization from the other end of the spectrum, the one in which humans are enhanced by machines, rather than machines becoming human. Holly is a soldier who has been implanted with hardware and software that allow her to hear the thoughts of everyone within a wide range. It’s painful, requiring her to live in a sort of cage lined with layers of fine wire mesh that keeps the voices away. But when Holly is on a mission, she becomes a part of a flying spy vessel with incredible capabilities. This would be sufficiently interesting all on its own, but the stakes increase when she is shot down on a mission and turned over to a Russian who has the same capability she has, and isn’t afraid to use it against her in the most brutal fashion possible. How Holly reacts, and what conclusions she comes to about the technology she has used, are fairly predictable, but the story is well-told nonetheless.

“Souvenirs” by Ian Creasey is a story about a seller of handmade objets d’art at a spaceport who is the victim of an unscrupulous customer who pays for her most expensive single object with a counterfeit bill. Fortunately for Kendra, the spaceport authorities take her complaint seriously. It’s a nice slice-of-future-life story in a world better than ours in some ways and worse in others.

“Greener,” by Josh Roseman, is a yarn about a man who divorces his wife and then regrets it. The only futuristic bits of the story is that the couple weren’t married, but contracted to each other; the divorce is not a divorce per se, but a refusal to renew the contract. They find their way back to each other, and ultimately bond forever in a way that I found mawkishly romantic and impractical. But love will do that to you sometimes. It’s the weakest story in this issue, but still well-written and tightly plotted.

I’m aware that I should automatically admire Carol Emshwiller’s writing. But “Riding Red Ted and Breathing Fire,” though charming, is not one of her strongest efforts. It is about a soldier who has been provided with a mutilated dragon to ride to a village owing a tithe to the central government; the dragon is supposed to be sufficiently intimidating to cause the recalcitrant village to comply. The soldier is pompous and arrogant, and one would expect him to be cut down to size in the typical story; but Emshwiller doesn’t write typical stories, and in this one the soldier finds an odd sort of redemption in the village he was to have terrified.

This issue also contains a books column by Norman Spinrad that is surprisingly dense and difficult to read, including extensive coverage of a novel available only in French. As interested as I am in science fiction and fantasy from other countries, I (and, I fear, most Americans) am unable to read a novel available only in a language I stopped studying nearly 40 years ago, and even Spinrad’s ecstasies make me unwilling to learn another language for the sake of this book. Another of Spinrad’s choices is a book he assures us is out of print and hard to find, a mash-up of voodoo and quantum physics. I’m perplexed by Spinrad’s choices, to say the least.

The poetry in this issue is generally not particularly good, though the first few stanzas of Bruce Boston’s “The Music of Particle Physics” are lovely, as these first few lines demonstrate: “The Music of Particle Physics / is absolutely relative, / precise and differential, / linear and curved.” That the poem loses its force at the end only makes it clear how difficult this business of science fictional poetry is.

Asimov’s maintains its position at the top of the heap of science fiction and fantasy magazines. I read this issue with great joy, and look forward to the next.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…

It's hardly a private conversation, Becky. You're welcome to add your 2 cents anytime!

If the state of the arts puzzles you, and you wonder why so many novels are "retellings" and formulaic rework,…

I picked my copy up last week and I can't wait to finish my current book and get started! I…