![]() Animal Man, Volume 2: Origin of the Species & Animal Man, Volume 3: Deus Ex Machina by Grant Morrison (writer) & Chas Truog (artist) issues 10-26

Animal Man, Volume 2: Origin of the Species & Animal Man, Volume 3: Deus Ex Machina by Grant Morrison (writer) & Chas Truog (artist) issues 10-26

These two volumes of Animal Man — Origin of the Species and Deus Ex Machina — complete the collection of Grant Morrison’s run on this once-minor DC character. This 26-issue run marks Morrison’s entry into American comics. The Scottish Morrison, along with Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore, is one of the three writers from the UK who helped change American comics for the better in the 1980s and 1990s. Moore preceded them in his work on Swamp Thing and is probably the reason Karen Berger from DC was sent to find more talent abroad, but Morrison and Gaiman are equally responsible for comics growing into a more thematically rich and mature popular art. The three of them were so successful that DC used their work — along with Jamie Delano’s on Hellblazer — to establish the Vertigo line of comics, a line dedicated to serious writing with almost no limits to what the comics could do in terms of content, theme, or genre. Being introduced to comics in my late 30s, the Vertigo label on a trade collection became my beacon, guiding me down the path of what was a new art form for me. I still follow it five years later.

These two volumes of Animal Man — Origin of the Species and Deus Ex Machina — complete the collection of Grant Morrison’s run on this once-minor DC character. This 26-issue run marks Morrison’s entry into American comics. The Scottish Morrison, along with Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore, is one of the three writers from the UK who helped change American comics for the better in the 1980s and 1990s. Moore preceded them in his work on Swamp Thing and is probably the reason Karen Berger from DC was sent to find more talent abroad, but Morrison and Gaiman are equally responsible for comics growing into a more thematically rich and mature popular art. The three of them were so successful that DC used their work — along with Jamie Delano’s on Hellblazer — to establish the Vertigo line of comics, a line dedicated to serious writing with almost no limits to what the comics could do in terms of content, theme, or genre. Being introduced to comics in my late 30s, the Vertigo label on a trade collection became my beacon, guiding me down the path of what was a new art form for me. I still follow it five years later.

I wonder why I stopped reading Morrison’s run on Animal Man. I finished the first volume years ago, and somehow the other volumes got pushed aside as I finished Sandman and then got sidetracked by Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, and countless other titles. I do know what got me to return to Animal Man: Reading Morrison’s half-commentary/half-autobiography Supergods, watching a great documentary on him, and reading his later work, particular All-Star Superman. The more I read by him and about him, the more fascinated I came by him. Few other comic book writers fascinate me in their thinking and writing outside of comics the way Morrison does. Gaiman and Moore are two of the very few other comic book writers who have led me to their non-fiction and documentaries (Warren Ellis is one more). Why do I read and seek out more than just comics by these writers? Because of the way they think about life as well as narrative. Or better yet, because of the way they think of life AS narrative. They see the playfulness of how the two merge. They also see the seriousness of it — what one postmodern theorist called, “serious play,” a term I’ve always liked.

I wonder why I stopped reading Morrison’s run on Animal Man. I finished the first volume years ago, and somehow the other volumes got pushed aside as I finished Sandman and then got sidetracked by Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, and countless other titles. I do know what got me to return to Animal Man: Reading Morrison’s half-commentary/half-autobiography Supergods, watching a great documentary on him, and reading his later work, particular All-Star Superman. The more I read by him and about him, the more fascinated I came by him. Few other comic book writers fascinate me in their thinking and writing outside of comics the way Morrison does. Gaiman and Moore are two of the very few other comic book writers who have led me to their non-fiction and documentaries (Warren Ellis is one more). Why do I read and seek out more than just comics by these writers? Because of the way they think about life as well as narrative. Or better yet, because of the way they think of life AS narrative. They see the playfulness of how the two merge. They also see the seriousness of it — what one postmodern theorist called, “serious play,” a term I’ve always liked.

In my previous review of the first volume of Animal Man, I discussed in great detail, though I didn’t use the term there, Morrison’s “serious play.” I proposed the theory that he is able to sell comics that are intellectually challenging and run the risk of not making any sense, or at least little sense, because he combines those challenging ideas with what would be merely insultingly didactic if left as the sole plot in another comic, particularly the animal rights and environmental concerns preached by the character Animal Man. Morrison seems very aware of this potential didacticism and not only talks about it in his introduction to volume one, but has  mentioned it in interviews and, most importantly of all, within the comic itself. Morrison famously steps into the comic toward the end of his Animal Man run and complains: “I felt I was turning the comic into a kind of ‘Animal Abuse of the Month’ Soapbox.” But one of the reasons I love Morrison’s work is that, as this example shows, as a creative writer, he figures out how to self-reflectively discuss his didacticism WITHIN the comic itself, creatively defusing its didactic nature through creativity.

mentioned it in interviews and, most importantly of all, within the comic itself. Morrison famously steps into the comic toward the end of his Animal Man run and complains: “I felt I was turning the comic into a kind of ‘Animal Abuse of the Month’ Soapbox.” But one of the reasons I love Morrison’s work is that, as this example shows, as a creative writer, he figures out how to self-reflectively discuss his didacticism WITHIN the comic itself, creatively defusing its didactic nature through creativity.

Another feature of Morrison’s “serious play” is that he takes what seems to be self-indulgent metafictional narrative and makes clear that there’s a serious reason for writing metafiction (by metafiction, here, I mean fiction that discusses within its creative boundaries its own nature as fiction, a quality of much of Morrison’s work). Perhaps the reason I stopped reading after volume one is that, though I really like it, there are certain aspects missing, the ones that make me absolutely love volumes two and three in comparison. And that’s saying something since I like volume one of Morrison’s Animal Man far more than most other comics I’ve ever read. The reason I like volumes two and three better — and volume three best of all — is that they start resolving all the confusing metafictional clues thrown at us in volume one. In fact, without the clear, often goofy, plots in volume one, the experimental aspects of volume one would make it almost unreadable to me. But volumes two and three make it clear that Morrison had a very clear plan regarding those weird parts worked out in his head as he was writing.

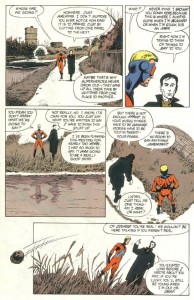

His crazy ideas in volume one do eventually make sense. They also have an excellent purpose. And, unlike in volume one, I find them incredibly engaging and entertaining on the plot level. So trust me, hang on for the entire ride offered in all 26 issues, and it’ll be worth it. Morrison’s final issues in volume three are the pay-off as the entire story seemingly goes off the rails, characters start realizing they are existing only in the world of comics, and they start breaking down the panels that try to keep them out of the gutters that lead into our world, the world in which their writer — Grant Morrison — and their gods — their readers — live.

His crazy ideas in volume one do eventually make sense. They also have an excellent purpose. And, unlike in volume one, I find them incredibly engaging and entertaining on the plot level. So trust me, hang on for the entire ride offered in all 26 issues, and it’ll be worth it. Morrison’s final issues in volume three are the pay-off as the entire story seemingly goes off the rails, characters start realizing they are existing only in the world of comics, and they start breaking down the panels that try to keep them out of the gutters that lead into our world, the world in which their writer — Grant Morrison — and their gods — their readers — live.

Though it’s not required reading, the reader unfamiliar with or new to comics, should know about Crisis on Infinite Earths (collected in trade). Bascially, DC, in order to clean up the confusion of their creative universe, had this story written to clear up discrepancies in continuity that had built up over the years. Some small things were changed; some large changes were made. There were shifts in characters in some ways, and as some clearing out was needed, many old characters were thrown out altogether.

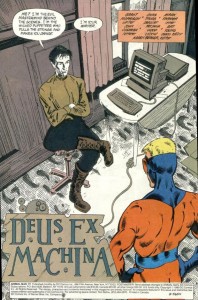

Why do you need to know about Crisis on Infinite Earths? Morrison, writing not too many years after this event, wants to reflect narratively on how a fictional universe written by many authors over the course of fifty years could just be shifted in the course of a single year by a single event, itself fictional. And what would happen to these poor characters? How would they feel if they could be brought back to life and told what happened to them? All these questions are answered in the course of Morrison’s Animal Man. It’s not surprising that a lot of this craziness happens within the walls of Arkham Asylum, DC’s number one insane asylum. So, on one level, Morrison deals with lost, forgotten, or discarded comic book characters. But he also deals with the one-on-one relationship between writer and character by having Animal Man — in the now-famous issue #26 — track him down and have a conversation with his own writer — Grant Morrison.

Why do you need to know about Crisis on Infinite Earths? Morrison, writing not too many years after this event, wants to reflect narratively on how a fictional universe written by many authors over the course of fifty years could just be shifted in the course of a single year by a single event, itself fictional. And what would happen to these poor characters? How would they feel if they could be brought back to life and told what happened to them? All these questions are answered in the course of Morrison’s Animal Man. It’s not surprising that a lot of this craziness happens within the walls of Arkham Asylum, DC’s number one insane asylum. So, on one level, Morrison deals with lost, forgotten, or discarded comic book characters. But he also deals with the one-on-one relationship between writer and character by having Animal Man — in the now-famous issue #26 — track him down and have a conversation with his own writer — Grant Morrison.

All of this metafiction certainly is playful. But what is the point? I think there are several points, and I think they are of interest to all of us who love to read. I try to review comic books for fantasyliterature.com that I think would appeal to those new to comics, and I try, as I’ve done here in discussing Crisis on Infinite Earths, to give enough information so that there is no other background knowledge in comics needed to enjoy the books I review. I want these reviews to serve as invitations to the world of comics, the invitations I wanted when I started reading comics and felt, as a newcomer to the party, very much left out of the conversations. These comics and their long history often seemed more daunting than inviting.

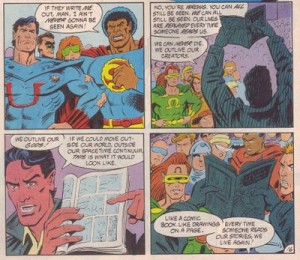

I think that Morrison speaks to all of us here at fanlit who return to a favorite book and revisit the characters whom we love and with whom we feel connected. This connection readers feel for fictional characters is addressed in a very funny scene in Arkham Asylum. All the characters previously-erased by the Crisis event are just starting to realize that they are fictional and are getting rightfully upset, but one of the characters is more optimistic in his reply to another character, Sunshine Superman (!), who says in shock and disbelief, “If they write me out, man, I ain’t never gonna be seen again!” Our optimist responds in a way that should resonate with all of us who have a favorite fictional character: “No, you’re wrong. You can all still be seen. We can all still be seen. Our lives are replayed every time someone reads us. We can never die. We outlive our creators. We outlive our Gods! . . . . Every time someone reads our stories, we live again!” Morrison also makes a little joke about how true that is in the world of comics considering how fans preserve their favorite comics in little plastic bags.

I think that Morrison speaks to all of us here at fanlit who return to a favorite book and revisit the characters whom we love and with whom we feel connected. This connection readers feel for fictional characters is addressed in a very funny scene in Arkham Asylum. All the characters previously-erased by the Crisis event are just starting to realize that they are fictional and are getting rightfully upset, but one of the characters is more optimistic in his reply to another character, Sunshine Superman (!), who says in shock and disbelief, “If they write me out, man, I ain’t never gonna be seen again!” Our optimist responds in a way that should resonate with all of us who have a favorite fictional character: “No, you’re wrong. You can all still be seen. We can all still be seen. Our lives are replayed every time someone reads us. We can never die. We outlive our creators. We outlive our Gods! . . . . Every time someone reads our stories, we live again!” Morrison also makes a little joke about how true that is in the world of comics considering how fans preserve their favorite comics in little plastic bags.

The main point is that Morrison uses all this metafictional playfulness to talk about the sacredness of reading and the way stories and the characters in those stories come alive for passionate readers. Surely you agree, otherwise you wouldn’t be reading fanlit about what to read! We are always searching for that next perfect book, that next set of characters with whom we can fall in love and bring to life.

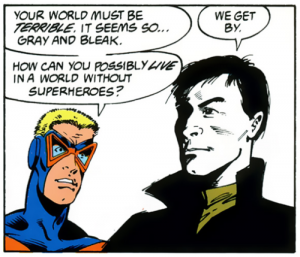

Morrison has other serious points he makes, one of which is a proposal for a reason for the necessity of fiction. Morrison, in a conversation with Animal Man, talks about how fiction is necessary for dealing with the harshness of our daily lives. He tells Animal Man that in comics, the characters always have hope. They are always dying and coming back to life. But in our world, people and animals die and don’t return. Morrison, portrayed in black-and-white as a colorless character compared to Animal Man, spends quite a bit of time, against the bleak backdrop of a black-and-white reality, telling Animal Man about his cat who died a long, painful death. Even more painful, as he emphasizes, is that the cat will never return. Animal Man, who was at first very angry with Morrison, has begun to sympathize with Morrison, with us, the readers, who live in this bleak, colorless world: “Your world must be terrible. It seems so gray and bleak. How can you possibly live in a world without superheroes?” Morrison’s first answer is merely that “We get by,” but his second answer is more significant: “If you want superheroes, I can give you superheroes.” And to me, this line is the key to Morrison’s entire run, perhaps to Morrison’s entire career. We need fiction, and therefore, we need writers to give us that fiction. There are as many reasons for fiction as there are problems in our world to which various fictions offer solutions or at least solace through acknowledgement.

Morrison has other serious points he makes, one of which is a proposal for a reason for the necessity of fiction. Morrison, in a conversation with Animal Man, talks about how fiction is necessary for dealing with the harshness of our daily lives. He tells Animal Man that in comics, the characters always have hope. They are always dying and coming back to life. But in our world, people and animals die and don’t return. Morrison, portrayed in black-and-white as a colorless character compared to Animal Man, spends quite a bit of time, against the bleak backdrop of a black-and-white reality, telling Animal Man about his cat who died a long, painful death. Even more painful, as he emphasizes, is that the cat will never return. Animal Man, who was at first very angry with Morrison, has begun to sympathize with Morrison, with us, the readers, who live in this bleak, colorless world: “Your world must be terrible. It seems so gray and bleak. How can you possibly live in a world without superheroes?” Morrison’s first answer is merely that “We get by,” but his second answer is more significant: “If you want superheroes, I can give you superheroes.” And to me, this line is the key to Morrison’s entire run, perhaps to Morrison’s entire career. We need fiction, and therefore, we need writers to give us that fiction. There are as many reasons for fiction as there are problems in our world to which various fictions offer solutions or at least solace through acknowledgement.

Animal Man shows Morrison at his best, when there is method to his madness, and I think there usually is method and reason to what often seem to be dizzying, mind-blowing stories. I base this claim not only on my reading of interviews, seeing his documentary, and reading his wonderful Supergods, but also based on what I’ve read of his comic book output: part of Doom Patrol, his various work on Batman, Batman Inc, Batman and Robin, Seven Soldiers, Flex Metallo, All-Star Superman, and more. But he started his American writing with Animal Man, and it shows his work fully almost matured from the beginning. Though I’ve revealed a few plot points, they are ones most people now know when they pick up Animal Man, and frankly, I think knowing them ahead of time will help the first-time reader: They should help you be patient with the weirdness in the early issues, knowing there’s a payoff in the end, and the few quotations I give here are merely to prove that Morrison knows what he’s doing AND to whet your appetite. Morrison makes countless other comments through Animal Man about reading, writing, comics, and fiction in general. But perhaps my favorite part of the final issue is the very end. One might wonder how Morrison would wrap up such a strange run on Animal Man. I just hope your curiosity is enough to make you find out for yourself.

It’s truly very difficult in this busy life to listen news on TV,

so I only use web foor thhat reason, and get the hottest news.

my webpage tgis post (http://www.youtube.com)