Across the Green Grass Fields by Seanan McGuire

Across the Green Grass Fields by Seanan McGuire

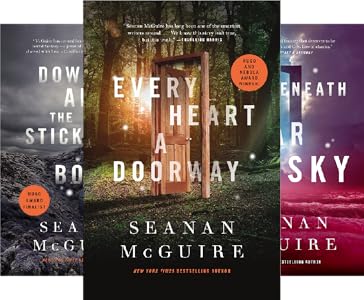

![]() I’ve been hit and miss on Seanan McGuire’s WAYWARD CHILDREN portal series, finding some of the novellas lyrical and emotional and others frustratingly slapdash. Her newest, Across the Green Grass Fields (2021), unfortunately falls closer to the latter end of the spectrum.

I’ve been hit and miss on Seanan McGuire’s WAYWARD CHILDREN portal series, finding some of the novellas lyrical and emotional and others frustratingly slapdash. Her newest, Across the Green Grass Fields (2021), unfortunately falls closer to the latter end of the spectrum.

As one expects by now, we have a young girl who steps through a doorway into another world. We meet Regan first at seven, part of a best friends trio with Heather Nelson and Laurel Anderson. Quickly, though, she gets drawn into one of those cruel moments of childhood where demarcations are drawn. When queen bee Laurel arbitrarily shuns Heather, deciding she isn’t “girly” enough, Regan, learning quickly “this is what it costs to be different,” goes along with it. Years pass and when Regan (now 11) learns the shocking secret her parents have been keeping from her — that she is intersex with XY instead of XX chromosomes — she foolishly confides in her “best friend”, who promptly (and predictably) responds with horror and condemnation. Fleeing the confrontation, Regan finds her doorway and steps through.

On the other side are “The Hooflands,” a land of centaurs and kelpies and kirins and other such creatures. Though Regan doesn’t meet most of these until the very end. Instead, she is found by a centaur and adopted into their small herd of isolated unicorn shepherds, becoming best friends with a young centaur named Chicory. Though she misses and mourns her parents, Regan quickly settles in and becomes a cherished member of the herd, constantly putting off her “destiny” — to be taken to the Queen so Regan can perform her heroic duty, which is always the case with humans who have found their way here: they save the Hooflands and disappear. When Regan, now 15, is allowed to join the herd at the Fair, though, events quickly escalate. She and the herd are forced to flee, and when Regan is separated, she meets some of the other inhabitants of the hooflands, with surprising results. Eventually though, destiny or not, Regan finds herself making her way with some unexpected companions to the Queen’s castle for a final confrontation that may or may not save the world and herself.

On the positive side, McGuire remains a smooth wordsmith. The novella moves along briskly and fluidly, with some lovely lines sprinkled throughout as well as some humor, as with McGuire’s subversion of the typical unicorn trope. The potential awfulness/cruelty of childhood, a running theme in McGuire’s work, is as always sharply, vividly conveyed. And the story has a solid message at its core, or several of them.

Unfortunately, for me the above positives were outweighed by the negatives. One is less a flaw than just a personal response. This book felt very YA to me, almost MG, and towards the very end, I even wrote in my notes it was starting to feel like a children’s illustrated book. So it skews very young. Not necessarily a bad thing, but because of that skewing it just doesn’t have the richness or complexity I prefer in my novels at this point in my life.

Somewhat related, though not entirely, it also felt very flat and almost perfunctory, glossing over or handwaving away plot and character points that were ripe for so much more development (and not just ripe for, I’d argue, but requiring much more development). Part of that, of course, is the form. There’s just not a lot of space in a novella. But then again, one can choose a story more fitting for the form (or change the form if the story overflows it).

As noted, the early scene about how cruel childhood can be is vividly presented, but it might be the only such scene. The scene where Regan learns of her intersexuality, for instance, felt more expository than emotive. Implausibly so. Something that seems almost acknowledged by the author when Regan tells her mother the conversation sounded like her mom was “reciting some Wikipedia article you memorized.” And the constant proclamations that Regan was “perfect” felt forced (more in the writerly sense than in the within-the-characters sense). The scene where she reveals her secret also feels forced, given that we’ve spent pages on how Regan has learned the cost of being different, how fiercely Laurel destroys those who don’t fit into neat categories, etc. Again, the scene is lampshaded by Regan’s internal monologue about how “despite Laurel being … “etc. she still told her, but it didn’t really make the moment more plausible. Finally, the whole intersex thing disappears soon after. It’s not that this needed to be a “special episode” story where Regan learns to deal with her intersexuality etc., but it’s hard to imagine it just never comes up in her mind again. In the Hooflands, we get a few tossaway lines about her missing her parents, but it never felt real or part of her. And then we get another implausible scene — this one an abduction — that only makes sense if everyone acts stupidly and that was signposted from the very start (I wrote in the margin— “hmm, wonder what will happen”). And again, having someone later say “we should have known better” doesn’t really excuse the scene. I’ll grant this may be less of an issue for an MG reader.

There were several other such instances I won’t go into. And some moments that felt, to use the term from above, slapdash or careless. Regan doesn’t “fully understand” what the reference to “D-cups is” from her mother, but a few pages earlier she’s mentioned how two groups of her acquaintances (at school and at the barn) were regularly talking about their developing breasts and it’s hard to imagine large breasts or cup size were never mentioned. Later, Regan is “shocked” when a creature suggests he’ll eat her when he had literally told her exactly that a few pages earlier. And there are other such moments, including a pretty big plot development that changes everything but makes no sense based on what came before, or is explained away in very weak form.

Finally, the last segment feels completely rushed and perfunctory, with things sliding into place in a fashion that felt, as I mentioned above, more akin to a picture book than a work for older readers. The resolution, meanwhile, was both darkly grim for a kid’s book and also unsubtly expositive/dogmatic in the form that children’s books often take, so it felt more than a little at odds with itself.

I know this is quite the beloved series, and my guess is this newest entry won’t do much to change that for fans. For me, while I can admire McGuire’s smooth style, the book’s flaws made it a far more frustrating than enjoyable read and one I can’t recommend.

~Bill Capossere

![]() Centaurs, unicorns, kelpies, fauns, perytons … Teenage Me would’ve loved this book. I was the type of girl who rode horses whenever the occasion offered and used my artistic talents to draw them, all the time, to the point where horses are still the only animal I can reliably draw well without needing to look at a picture. So I came to Across the Green Grass Fields predisposed to like it.

Centaurs, unicorns, kelpies, fauns, perytons … Teenage Me would’ve loved this book. I was the type of girl who rode horses whenever the occasion offered and used my artistic talents to draw them, all the time, to the point where horses are still the only animal I can reliably draw well without needing to look at a picture. So I came to Across the Green Grass Fields predisposed to like it.

Ten-year-old Regan adores horses and rides them regularly. She also has a mother and a father who are loving and attentive (something that can’t be taken for granted in YA fiction), as well as a close school friend named Laurel whose friendship Regan has hung onto for years. Laurel is clearly the toxic queen bee type, but Regan remains Laurel’s loyal shadow for several more years, even after Laurel permanently and cruelly rejects their other best friend, Heather, for bringing a snake to school (snakes not being as socially acceptable as horses). Regan somehow doesn’t fully realize, or maybe just doesn’t want to admit to herself, that Laurel could turn against her as quickly and terribly.

This being a WAYWARD CHILDREN novella, it’s a foregone conclusion that Regan will be different from the norm in some significant way. When Regan is ten going on eleven, she confronts her parents about why she isn’t physically maturing yet, and finds out that she’s intersex. Though her parents break the news as gently as they can, Regan’s world is rocked, and she makes the mistake of confiding in Laurel. I have to digress for a moment to say that, even with the abundance of mythological creatures in this book, Regan’s choice to disclose her physical difference to Laurel was probably the most unbelievable thing in the whole novel for me.

Regan had known from the beginning that Laurel’s love was conditional. It came with so many strings that it was easy to get tangled inside it, unable to even consider trying to break free.

Regan knows, far better than most girls, how unforgiving Laurel is of anyone who doesn’t conform to the norm and how cruelly she can lash out, and no amount of McGuire’s explaining why Regan made this choice made it seem a likely one to me.

Be that as it may, things predictably go wrong fast, Regan runs away from school — and finds herself faced with a magical doorway in the woods that leads to the Hooflands. The Hooflands is inhabited by large, muscular centaurs, lovely and brainless unicorns, carnivorous kelpies, and every other imaginable creature with hooves … except horses (“What’s a horse?” asks one of the centaurs). Everyone has hooves of some kind, and humans are exotic creatures that show up once in a blue moon to heroically save the Hooflands from some terrible trouble and then disappear. Destiny? or perhaps not. In any case, Regan and the centaur herd that adopts her are in no hurry to send her to the queen of the Hooflands to face whatever trial may await.

McGuire spends a full quarter of Across the Green Grass Fields describing Regan’s childhood in our world, particularly the “vicious political landscape of the playground, where the slightest sign of aberration or strangeness was enough to bring about instant ostracism.” It’s well-told, with sympathy for everyone involved (well, except Laurel). In the Hooflands, Regan finds true friendship for the first time and begins to accept herself and understand that being “normal” is not the be-all and end-all she had thought it was. The tone shifts gears to become a pastoral, fairly slow-paced story, with the exception of one fairly frantic chapter. Even the climactic scenes toward the end of the novella don’t achieve any real sense of urgency. Also, while these final scenes do slot in with the themes that McGuire has been addressing throughout the book, they felt rushed, and the same sense of improbability resurfaces around the events that occur toward the end. Maybe Seanan McGuire wrote this a little too quickly, or maybe she’s just more focused on themes than plot. I really wanted more of an epilogue … in both the Hooflands and in our world.

This entry in the WAYWARD CHILDREN series doesn’t have any obvious links to Eleanor’s Home for Wayward Children or the characters in the other books in the series, at least at this point. Across the Green Grass Fields does have some great moments and poignant insights into human nature and life, but it lacks the full impact that the best books in this series have.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this review, Teenage Me would’ve loved this book. Adult Me sees the narrative flaws in it, but I was still moved by the characters and their obstacles. Across the Green Grass Fields is worth reading if you’re a fan of the series.

~Tadiana Jones

We’re in total agreement David!

I felt just the same. The prose and character work was excellent. The larger story was unsatisfying, especially compared to…

Hmmm. I think I'll pass.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…