Reading Comics, Part 4: Mind the Gutter

by Dr. Brad K. Hawley

We could proceed to talk about the way comics use words to tell stories, but in many ways, they share much in common with all fictional narrative. A book on interpreting literature, then, is helpful for reading comics, and it should come as no surprise that I’ve found English majors well-prepared to analyze the way comic books communicate meaning.

But I’ve demonstrated that the ability to interpret a novel is not enough when reading comics. The use of images turns comics into something neither less than nor more than a novel — comics are clearly something else. But they do resemble another art: Movies. And I’ve found students who have taken courses in film studies are also good at discussing comics. They can see how camera angles and perspectives in film are similar to the visual vocabulary of comic books. The careful placement of objects and shifts in visual points-of-view are just as important in comics as in film.

However, unlike movies (or animated movies, let’s say, which really seem to resemble the comic), comic books don’t provide fluid motion and require a kind of active participation that is not a part of movies (though they have their own types of audience participation). The lack of fluidity is a product of the gutter, a key component of comics which separates comics from all other arts. As many critics of comics have pointed out, the gutter is the visual key to comics. The gutter is the place where nothing — and yet everything — happens.

The gutter is the blank space between panels in a comic book; it’s the chasm our minds attempt to cross. At times the crossing may be easy, and at times it may be difficult, but it’s never a completely passive experience on the part of the comic reader. Studying the gutter helps us understand how much a comic book requires mental engagement on the part of the audience. The way the artist forces our minds to connect the panels will lead to different types of interpretations than others, some more obvious than others.

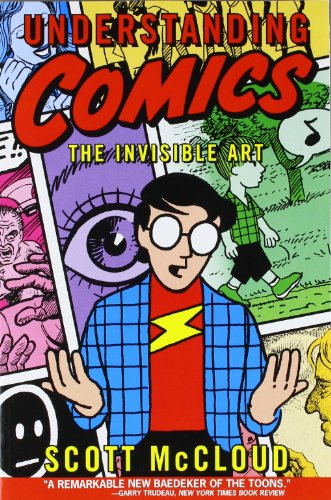

Scott McCloud, in his insightful, seminal comic book on comic books —Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art — identifies six different types of panel-to-panel transitions. The first — going from moment-to-moment — can show the blink of an eye. And the last — the non-sequitor — is the most open to interpretation because it forces the reader to guess the connection between two panels. The other four — action-to-action, subject-to-subject, scene-to-scene, and aspect-to-aspect — fall between these two types.

At the moment, trying to memorize, or even fully understand, each one is not that important. What is important as you start appreciating your first comic books is being aware that the jumps in space, time, and concept may be minor or they may be major; simple, or downright baffling. But either way, you should notice that if you have three panels of the same size in a row, for example, you could see the blink of an eye from panel one to panel two, but from panel two to panel three, a character could have moved to another country, aged forty years, lost or gained a fortune, and changed her philosophy on life. Each artist will make his own demands on you.

At the moment, trying to memorize, or even fully understand, each one is not that important. What is important as you start appreciating your first comic books is being aware that the jumps in space, time, and concept may be minor or they may be major; simple, or downright baffling. But either way, you should notice that if you have three panels of the same size in a row, for example, you could see the blink of an eye from panel one to panel two, but from panel two to panel three, a character could have moved to another country, aged forty years, lost or gained a fortune, and changed her philosophy on life. Each artist will make his own demands on you.

The truth is that comics are a demanding art, and I’ve barely scratched the surface of what goes into comics: We could discuss more detailed aspects of the use of color, the use of different artistic techniques, the influence of Manga, and other worthwhile subjects concerning contemporary comics. But we can see that comics are an art form for adults worth studying, respecting, and, most importantly, enjoying. There continue to be comic books made for young kids, but if you walk into a comic shop and flip through the pages of most comic books, you’ll soon realize that many young teenagers aren’t mature enough to deal with the content of contemporary comics, much less able to intellectually grasp the complex story-telling techniques and the rich thematic tapestry that is woven together by the best artistic teams year-in-and-year-out in some consistently impressive story-lines. Ed Brubaker, my favorite comic book writer, for example is able to impress me issue after issue with his Captain America title, a character I couldn’t care less about if it weren’t written by Brubaker.

There’s a rich history of comic books, and even the ones you think you might not be interested in, if they’re written by the best writers, are crafted with both reverence and irony, a strange combination, but one that can be understood if you think of the last time you made fun of an older, quirky relative while still loving and respecting him. This loving, but ironic stance defines the current approach of the best writers to the superheroes you think you don’t want to read about. And if you still don’t want to read about superheroes, you don’t have to. You could fill an entire library with trade collections of non-superhero comic books.

There’s a rich history of comic books, and even the ones you think you might not be interested in, if they’re written by the best writers, are crafted with both reverence and irony, a strange combination, but one that can be understood if you think of the last time you made fun of an older, quirky relative while still loving and respecting him. This loving, but ironic stance defines the current approach of the best writers to the superheroes you think you don’t want to read about. And if you still don’t want to read about superheroes, you don’t have to. You could fill an entire library with trade collections of non-superhero comic books.

Just remember this: You don’t dislike comics, and you never will dislike them: You just haven’t found the ones you like yet. In the next part of this essay, I will offer reading suggestions cutting across multiple genres, with an emphasis on accessible, contemporary comics for the adult reader.

Next time: Part 5, Good Reference Material

I think the gutter has been a problem for me, but I see that I need to be more engaged with the story and perhaps make some of my own inferences.

The only comic that I really like (or think I like), GIRL GENIUS, doesn’t have as much going on in the gutter, which is probably why it’s easier for me. Plus, I love the art, so I pay more attention to it.

That’s one of the things I’ve grown to enjoy in comics as I’ve gotten older is the flow of the story as controlled by the “gutter” -I didn’t know that term before.

Many modern comics do a lot of jumping around, which can really throw you off sometimes and often you have to take a very close look at the illustrations or you’ll miss key elements.

I believe too many new comic readers, think of comics books and graphic novels as a glorified picture book like what they read as children and go into comics with low expectations. So it’s not realized that a lot imaginative thinking is still required to interpret the story. And that the stories in comics are still very much open to individual interpretation, just as a traditional novel is.

Brad– I have really enjoyed your columns. I have a friend who has sold two graphic novels (one is an Eisner winner) and who often blogs about the drawing/writing process. I’m going to send him the link to this post because I think he’ll really enjoy it. And then he’ll go back and read the others. Thanks, please keep them coming!

I’d love to read this Eisner-winning graphic novel. Title?

Brad– Mom’s Cancer by Brian Fies, Abrams is the publisher. (I’m sure that’s not spelled right.) He also wrote Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow?

I bought Amulet today (It’s young adult) and in the prologue, I noticed how the gutter was being used to add the sense of chaos of the fatal car wreck.

Marion

I just ordered both books. They look really interesting. And I purchased the Amulet series for my daughter back in August, but I haven’t read it yet. I’ll have to get back to you on all these . . .

Brad–can’t wait to hear your opinions.

Brubaker is a great choice to enjoy. Like musical duets and groups, putting together the right combination of writer-artist can be harmonious on the comic book page. In the case of Brubaker, it would be Steve Epting as his artistic collaborator on Captain America. I highly recommend the Winter Soldier run up to the point of where Cap gets mortally wounded. As is the beauty of trade paperbacks, the Winter Soldier storyline can be collected in a few trades without hunting down the single issues.

His Daredevil and Iron Fist runs are also very excellent. He is highly regarded in the industry for his stellar and consistent storywriting.