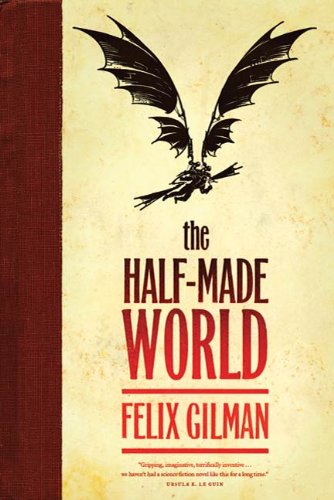

Felix Gilman is the author of several well-received novels: Thunderer, Gears of the City, and The Half-Made World (which made my top ten list last year). His newest, The Rise of Ransom City, is a wonderfully unconventional follow-up to The Half-Made World (here’s my review). He recently took some time to answer a few questions, including why he opted against writing a more typical sequel and what projects he is currently working on. You can find out more by visiting Felix Gilman’s website. But really, what you should do is just go read his books. And if you’d like a chance to win a copy of The Rise of Ransom City, just leave a comment below.

Bill: One of the aspects of fantasy I enjoy as a fan is the way the metaphor can become literal. Can you speak at all to the genesis of the idea for the underlying metaphor of the Line and the Gun and their war? I’m especially curious as to how it related to your setting — did you originally have a Western motif in mind and the Line and Gun grew organically out of that, or did you have the war in mind and found a form to fit the conflict, or some other process? I’m also curious as to the balance between them and how carefully you crafted that. It seems that the Line, with its fascist order-obsessed tendencies, pollution, noise, and environmental devastation (the Scouring of the Shire on a huge scale it seems to me) is almost doomed to be the one that readers would reject out of hand when set against the lone Western gunman — such an archetypical image, one we’re almost trained to root for out of instinct by now. Was that a concern of yours at all and did you craft the Agents of the Gun so as to work against or with (enjoying perhaps the discomfited reader) our predilection to root for the gunslingers?

Felix Gilman: It’s hard to recall at this point exactly where I started; I’ve now spent so long working on these books that I don’t know that my memories are entirely trustworthy. But with that caveat, the way I seem to recall it now is that I started with the character of Creedmoor, who was going somewhere and planning to do something horrible, and talking to himself — showing off for himself about what a bad man he was. Liv showed up soon after. The western motif grew out of the two characters, and then the Line and the Gun grew out of that — taking big themes for that sort of a setting and making them literal, as you say.

Felix Gilman: It’s hard to recall at this point exactly where I started; I’ve now spent so long working on these books that I don’t know that my memories are entirely trustworthy. But with that caveat, the way I seem to recall it now is that I started with the character of Creedmoor, who was going somewhere and planning to do something horrible, and talking to himself — showing off for himself about what a bad man he was. Liv showed up soon after. The western motif grew out of the two characters, and then the Line and the Gun grew out of that — taking big themes for that sort of a setting and making them literal, as you say.

I tried to balance them. I mean they’re both supposed to be awful really, they’re both huge destructive mass derangements. But I agree, reader identification is likely to tip toward the Gun. The Gun is a glamorous, romantic, individualist power fantasy. It doesn’t work unless it’s seductive; but I hope I made them clearly both glamorous and deeply screwed up. Creedmoor really does do some awful things, for not very much reason. But you know that line about how it’s impossible to make an anti-war movie? It may also be impossible to write an anti-power-fantasy.

I crave reader discomfort, I hunger for it.

Bill: Still on that topic, one of the things I liked about that metaphor was that it didn’t feel overly restrictive or didactic — it felt grounded enough that readers would probably find some broadly shared meaning in it, but open-ended enough that any two readers might have different shades of that shared meaning. Were you careful to avoid funneling readers down a certain path or did you have a specific “message” or analogy you were trying to convey?

Bill: Still on that topic, one of the things I liked about that metaphor was that it didn’t feel overly restrictive or didactic — it felt grounded enough that readers would probably find some broadly shared meaning in it, but open-ended enough that any two readers might have different shades of that shared meaning. Were you careful to avoid funneling readers down a certain path or did you have a specific “message” or analogy you were trying to convey?

Felix: I don’t have a specific message (notwithstanding the above; I have a way that I read things but don’t want it to foreclose other readings). When constructing the story and setting I’m much more concerned about what feels interesting, compelling, aesthetically right, than about what supports a consistent argument.

Bill: I called The Rise of Ransom City a “kinda-sorta” sequel, saying it continued the story of The Half-Made World but did so “slant-wise.” What led you to picking up with a wholly new character and making Liv and Creedmoor’s story more a tangent to Harry’s tale? Was this your first choice or did you begin with a more conventional pick-up-where-we-left-off sequel?

Felix: I had a try at starting a more conventional sequel. The thing is that at the point at which Liv and Creedmoor’s story becomes most central to big-world-changing-events, it becomes least interesting to me. I wanted to try to shift the focus so that we’re seeing the big events the way we all actually see big events in real life — from a distance, filtered through layers of bullshit and our own obsessions. And I like leaving things to the reader’s imagination.

Harry started as a co-character and then as I drafted and re-drafted he shifted into the protagonist and then quickly took over as narrator. That was just a fact about the character, I think. He’s too talkative; he doesn’t work from third-person perspective.

Bill: I absolutely loved both Harry’s character and his voice; it reminded me of Horatio Alger telling Huck Finn’s sequel (keeping Twain’s wry, folksy humor) if Huck had been possessed by the spirit of Nikola Tesla. Did his voice come to you pretty quickly or did you struggle to nail it down?

Bill: I absolutely loved both Harry’s character and his voice; it reminded me of Horatio Alger telling Huck Finn’s sequel (keeping Twain’s wry, folksy humor) if Huck had been possessed by the spirit of Nikola Tesla. Did his voice come to you pretty quickly or did you struggle to nail it down?

Felix: Thank you! Twain is probably my Favorite Great Dead American. The story nods to Alger and Tesla, definitely.

It came pretty easily, really. It’s not a million miles from my own inner monologue. I had to spend some time editing for small points of consistency (does he say anyway or anyhow, does he use semicolons (he does not, whereas I love them) etc etc).

Bill: I thought there was a sense of uncertainty that runs throughout both books. The world is “Half-Made,” the Line and Gun are in some ways quite abstract, Harry’s Apparatus is always unpredictable and never fully explained. We don’t always find out what happened to various characters or what various events mean or what their causes are. I felt it worked perfectly with the setting — this frontier kind of world where people and towns are still creating and re-creating themselves, feeling their way to just who/what they are going to be. Do you see this same uncertainty throughout and if so, is it purposeful on your part? If it was, were you ever concerned that it might leave some readers frustrated?

Felix: Definitely purposeful. And this goes to the shift in POV in the sequel: a sequel can either spell out things that were left ambiguous before, or it can add to the uncertainty, and shifting from an omniscient third-person narrator to a somewhat untrustworthy first-person narrator is one way of doing that.

Yes, I worry that it leaves some readers frustrated. I mean I like frustrating reader expectations (see above) and as a reader myself, my favorite books are often ones that frustrate my expectations, don’t give me what I think I want, leave me uncertain and confused and forced to fill in the gaps. At the same time I don’t want people to go away angry and disappointed. I want people to feel they got their money’s worth, I want them to go away and say nice things about the books on social media, I crave external validation. You have to try to hit a balance between too much and not enough, and inevitably some readers are going to find that you’ve shown not enough and some that you’ve shown too much. Ultimately you have to write what works for you, I think it’s hard — pretty much paralyzing — to try to write for an ideal reader other than yourself.

Yes, I worry that it leaves some readers frustrated. I mean I like frustrating reader expectations (see above) and as a reader myself, my favorite books are often ones that frustrate my expectations, don’t give me what I think I want, leave me uncertain and confused and forced to fill in the gaps. At the same time I don’t want people to go away angry and disappointed. I want people to feel they got their money’s worth, I want them to go away and say nice things about the books on social media, I crave external validation. You have to try to hit a balance between too much and not enough, and inevitably some readers are going to find that you’ve shown not enough and some that you’ve shown too much. Ultimately you have to write what works for you, I think it’s hard — pretty much paralyzing — to try to write for an ideal reader other than yourself.

Bill: Somewhat in that vein, I’m wondering if a large portion of what these two books deal with is storytelling itself. The American West, after all, as we usually think of it is a wholly created myth, a story we tell ourselves about our creation, about ourselves. Stories — reputations, dime novels, newspaper articles, word of mouth tales — play a big role in both works. Harry himself says one of his purposes is to correct the stories told about him. In The Rise of Ransom City, we have a story via an unreliable narrator. A story that is itself incomplete and unfinished and filtered through the editing/compiling by another character who tells us via footnotes for instance that some of what we’re reading isn’t wholly factual or tells us how some of it has been written and rewritten multiple times. Is this just something that appears as a matter of course, spilling out of someone who, as a writer, is naturally focused on stories and story-telling, or is this something you set out to emphasize?

Felix: This is a great comment, and exactly right, and I wish I had something more to add to it than this. It’s something I set out to emphasize in both books.

Bill: Finally, while one can happily read The Rise of Ransom City as a picaresque adventure story told by a well-meaning raconteur, the story offers up lots of opportunity to stop and think deeply about politics, economics, sociology; about the encroachment of modernity and technology and what it does to us as well as for us; about the way we mythologize guns and violence and isolated actors; about what are the best ways to govern ourselves as an interdependent society; about what are the best ways to ensure a level of dignity and material comfort, and so forth. On one level, of course, it’s hard to write a novel involving more than one character that doesn’t in some way explore politics/economics/sociology. But from your perspective, is this something you try to emphasize, removing these concepts from simple background coloration and setting them front and center to provoke readers into a more thoughtful exploration of issues?

Bill: Finally, while one can happily read The Rise of Ransom City as a picaresque adventure story told by a well-meaning raconteur, the story offers up lots of opportunity to stop and think deeply about politics, economics, sociology; about the encroachment of modernity and technology and what it does to us as well as for us; about the way we mythologize guns and violence and isolated actors; about what are the best ways to govern ourselves as an interdependent society; about what are the best ways to ensure a level of dignity and material comfort, and so forth. On one level, of course, it’s hard to write a novel involving more than one character that doesn’t in some way explore politics/economics/sociology. But from your perspective, is this something you try to emphasize, removing these concepts from simple background coloration and setting them front and center to provoke readers into a more thoughtful exploration of issues?

Felix: This is also a great comment! (These are all very interesting questions and I have enjoyed answering them a great deal)

I agree that all novels involving more than one character are in some sense political, unless they’re in different rooms. Maybe even one character alone in a room with a gun is political.

As I said above, I don’t want to construct the books in such a way that they force a particular message. Didacticism is tiresome anywhere, but particularly silly in secondary world fantasy, where of course politics works the way you say it does because you made up the world. On the other hand, these books are obviously using a lot of heavily politically-loaded concepts. The frontier itself is a politically-loaded concept (frontier to what?) — myths about lone gunslingers are political, the Horatio Alger stories that are part of the framework of Ransom City are heavily political, etc etc. The rise and fall of the Red Republic collapses attributes of the Revolution and the Civil War into one, and what’s that all about. I suppose to the extent there is a method to this beyond the purely aesthetic it’s that I think taking these ideas out of context and knocking them together helps one to see them as contingent, as socially constructed, as questionable. Maybe, who knows.

Bill: Can you give us any sense of other works coming down the pipeline? Any plans to revisit this world — either via another novel or some shorter works set in the same world?

Felix: I might revisit this world. Depends on interest, and time. I don’t have enough time to do most of the things I want (who does?) Despite everything I said above I am sort of interested in returning to Liv and Creedmoor to fill in some of the gaps. I started a short story a little while ago but it didn’t really go anywhere beyond “boy I wish I’d written True Grit” so I abandoned it. I have a mad plan somewhere in the back of my mind to do a third book that advances the setting to something reminiscent of the 1960s but I don’t know if I can convince anyone to publish that.

Felix: I might revisit this world. Depends on interest, and time. I don’t have enough time to do most of the things I want (who does?) Despite everything I said above I am sort of interested in returning to Liv and Creedmoor to fill in some of the gaps. I started a short story a little while ago but it didn’t really go anywhere beyond “boy I wish I’d written True Grit” so I abandoned it. I have a mad plan somewhere in the back of my mind to do a third book that advances the setting to something reminiscent of the 1960s but I don’t know if I can convince anyone to publish that.

Other works coming down the pipeline: I’ve recently finished a draft of a new thing, about late-Victorian occultists, who by the aid of astral projection and drugs travel to Mars, sort of. Tentative title is The Revolutions (as in On The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres; does that title work or does it need too much explanation? I don’t know). I’m starting on a new thing that is sort of related to that, though again slant-wise; it’s heavily influenced by John Mandeville’s Travels — a 14th century story of world travel mostly composed of apocrypha, bullshit, and myth.

Bill: What sort of reading do you do outside the genre? Any recommendations of some good books you’ve read recently?

Felix: A lot of my reading recently has been related to the two recent book projects. So for The Revolutions I read a lot of Arthur Conan Doyle and H. Rider Haggard and Burroughs and Edwin Arnold and a lot of spiritualist stuff. Thank God for Project Gutenberg. For the new thing I’m reading a lot of medieval history and contemporary writing (e.g. Mandeville). Been a while since I read any fiction not connected with a writing project, to be honest. Here’s a recommendation of a book I re-read in connection with the medieval thing — Barry Unsworth’s Morality Play. It’s about a troupe of players in the fourteenth century, and a murder mystery. Very good historical fiction.

Felix: A lot of my reading recently has been related to the two recent book projects. So for The Revolutions I read a lot of Arthur Conan Doyle and H. Rider Haggard and Burroughs and Edwin Arnold and a lot of spiritualist stuff. Thank God for Project Gutenberg. For the new thing I’m reading a lot of medieval history and contemporary writing (e.g. Mandeville). Been a while since I read any fiction not connected with a writing project, to be honest. Here’s a recommendation of a book I re-read in connection with the medieval thing — Barry Unsworth’s Morality Play. It’s about a troupe of players in the fourteenth century, and a murder mystery. Very good historical fiction.

Here’s another recommendation, randomly selected from things on my desk: Adam Thorpe’s Flight. UK readers are much more likely to have heard of him than US readers. He’s a Very Grand Literary Novelist turning, in Flight, to what is essentially a thriller, complete with assassins with AK-47s, people being dangled off balconies by goons, the works. He really pulls it off, it’s great.

Here’s another recommendation, randomly selected from things on my desk: Adam Thorpe’s Flight. UK readers are much more likely to have heard of him than US readers. He’s a Very Grand Literary Novelist turning, in Flight, to what is essentially a thriller, complete with assassins with AK-47s, people being dangled off balconies by goons, the works. He really pulls it off, it’s great.

Bill: Finally, a question I always like to ask is if you can recall for us one or two of those magical moments of response to a particular scene in a book or two — those sort of “shiver moments” that make one fall in love with the magic of reading all over again or that we carry with us for years afterward.

Felix: What springs to mind right now isn’t a scene, but a phrase. The other day I happened to see the phrase “When the wolves were running” and it sent a shiver down my spine; those who remember The Box Of Delights from their childhoods may remember that phrase.

Bill: Thanks for the chat, Felix!

Readers, comment below for a chance to win a copy of The Rise of Ransom City.

Me please! Loved the first book.

Just leaving a comment :)

I’ve never read anything by Felix but I think I have to. Remedy that

I put these books on my list after you reviewed them, Bill. I haven’t had a chance to read them yet, but I am looking forward to it!

I keep finding new books I have to read.

Also, Felix looks startling similar to Irish actor Dylan Moran.

Wow Ruth, he really does. Have we ever seen them in the same room together?

Can’t wait to hear what you guys think (unless, of course, it’s “what the hell was Bill talking about?!”) But I’m pretty sure you’ll like these

I was blown away by Thunderer, was sucked in by Gears of the City and pleasantly surprised by the direction of Half Made World. Felix is now on my list of authors whose books are a necessity for me.

I really enjoyed the interview, I’ve got to check out Felix Gilman’s books. :D

I’m halfway through the Half Made World and thoroughly enjoying it. Fantastic interview.

One of the best steampunk books I have a read in a long time. Consider this my entry into the contest.

Andris Bekmanis, if you live in the USA, you win the dice roll and the book. Please contact me (Tim) with your choice and a US address.

I’ll be reading this, that’s for sure.