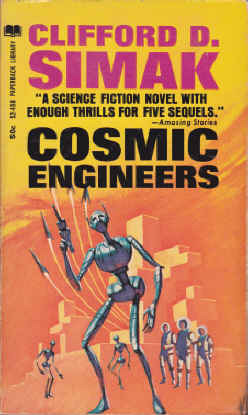

![]() Cosmic Engineers by Clifford D. Simak

Cosmic Engineers by Clifford D. Simak

Every great novelist has to begin somewhere, and for future sci-fi Grand Master Clifford D. Simak, that beginning was his first novel, Cosmic Engineers. This is not to say, of course, that this novel was the first attempt at writing that Simak had ever made. Far from it, as a matter of fact. Cosmic Engineers originally appeared as a three-part serial in the February – April 1939 issues of John W. Campbell’s highly influential Astounding Science-Fiction magazine, and in a slightly expanded book form 11 years later. But before 1939, Simak had placed no fewer than 10 short stories in the pages of ASF and Thrilling Wonder Stories, while at the same time working as a journalist on the Minneapolis Star & Tribune, his “day job” until his retirement in 1976, at age 72.

Cosmic Engineers is an atypical book for this beloved author, displaying little if any of his later, “gentle” style, pastoral leanings, and settings in rural Wisconsin. (There IS one passage, however, in which one of the characters declares “There are some things that never change. The smell of fresh-plowed fields and the scent of hayfields at harvest time and the beauty of trees against the skyline at evening…”) It is, rather, a novel of fairly hard science, a genre that Campbell (an ex-MIT student and aspiring engineer himself) highly favored, mixed in with a goodly dollop of “sense of wonder” writing that was deemed so very essential for Golden Age sci-fi. The result is a just barely pleasing, mixed affair that should come as a surprise to all of Simak’s many fans.

In the book, the reader meets Gary Nelson and Herb Harper, reporter and photographer, respectively, for the Evening Rocket. On board their cramped Space Pup, the two have been roaming the solar system, doing a continuing weekly column on the manifold wonders of the nine planets. Before long, however, they get the story of their careers when they discover a 1,000-year-old craft in orbit around Pluto. Inside the small ship lies a young woman in suspended animation, who, when revived, admits to being none other than Caroline Martin, a scientific genius who had been unfairly charged with treason a millennium earlier and marooned in an orbiting prison. She’d placed herself into the suspended animation state but had not reckoned with the fact that, although her body would remain in stasis, her mind would remain active. Thus, the young woman had been, for 1,000 years, pondering the mysteries of space and time, and developing her gift for telepathy. And Caroline’s newly awakened skills are soon to be tried to their utmost.

Dr. Kingsley, a researcher on Pluto, has recently been picking up messages from the very fringe of our universe, at the very edge of where the time/space continuum ends; messages imploring assistance to avert some kind of large-scale catastrophe. Using instructions from these so-called Cosmic Engineers, Kingsley and Caroline construct a stabilizing portal that will open up a space-time warp and enable rocket hotshot Tommy Evans’ faster-than-light starship to traverse the billions of light-years in moments. Thus, the quintet eventually reaches the home world of the telepathic, metallic-looking Cosmic Engineers in good time, only to learn the shocking truth: Our universe is just one of many billions, and very shortly will be coming into collision with another! The “friction” generated by the initial rubbing of the two universes will generate enough energy to completely destroy both! And as if that weren’t enough, a race known only as the Hellhounds is engaged in an ongoing war with the Engineers, and is actually trying to facilitate the universe’s extinction!

In a set of books that this reader just reviewed, Wylie & Balmer’s When Worlds Collide (1933) and After Worlds Collide (1935), the Earth and its moon are destroyed in spectacular fashion in a collision with the rogue planet dubbed Bronson Alpha, but a mere destruction of worlds seems to have been deemed small potatoes for Simak in his first novel. Indeed, the author’s main intention here, one gets the feeling, was to write as large-scale and mind-blowing a novel as he possibly could, rife with cosmic speculations, origin theories for the birth of mankind on Earth, time travel, bizarre-looking aliens, weapons of superscience, and, as mentioned, the wholesale destruction of two universes. He touches on the possibility of a planet’s having a myriad of possible “parallel” realities, a concept dealt with in much fuller detail in the author’s brilliant novel of 1953, Ring Around the Sun. Simak’s first novel is simply and plainly written, verging at times on what is now known as YA — fans of lyrical prose, such as that sported by such authors as Clark Ashton Smith and Lord Dunsany, should not expect anything on the order of beautiful verbiage here — but still manages to perplex the reader when he delves into such matters as hyperspheres, miniature universes, interspace, and five-dimensional space. The first-time novelist does manage to get in some pleasingly written passages, such as this one, in which Gary contemplates the possibility of parallel Earths:

His mind whirled at the thought of it, at the astounding vista of possibilities that the thought brought up, the infinite number of possibilities that existed as shadows, each with a queer shadow existence of its very own, things that just missed being realities. Disappointed ghosts, he thought, wailing their way through the eternity of nonexistence…

But at the same time, Simak turns in some real clinkers in the prose department, such as when he tells us “Its skin was mottled and its eyes were narrow, slitted eyes,” and “A slinking shape slunk across a dune.” Oy. Likewise, ungrammatical sentences abound, such as “…someone had tidied up before they walked off…” Was this book ever copyedited by editor Campbell?

The book, unfortunately, comes freighted with some other minor problems. It is set in the year 6948, and yet seems to take place only a few hundred years in our future; 1,000, at the very most. Simak manages to get some basic facts incorrect in his first novel, too. He mentions that the age of the Earth is 3 billion years, whereas we now know that it is closer to 4.5 billion, and tells us that the Andromeda galaxy is a whopping 900 million light-years from Earth, instead of the more accurate figure of 2.5 million! Overall, the novel lacks descriptive detail, and perhaps should have been twice as long as it is. (The time-travel trip that Gary and Caroline make to the Earth of millions of years hence takes up a mere 12 pages, for example.) Characterization is sketchy, at best, and the potentialities of such imaginative constructs as a woman who’s developed her mental powers over a millennium, the harnessing of the interspace energies, the Engineers’ precise relationship with mankind, and the backstory of those reptilian Hellhounds are left, sadly, unrealized. Simak, thus, here displays an abundance of imaginative ideas but does not flesh out his ideas sufficiently to engender believability. I would categorize it as an excellent first effort by a talented amateur writer; one who shows great promise, to be sure.

Writing of Simak’s novel in his Ultimate Guide to Science Fiction, Scottish critic David Pringle tells us that it is an “amusingly inept space opera … best left buried”; author and critic Damon Knight would seem to agree, and has called the book “a potboiler [that] should have been left interred.” Ouch! Both critics, I feel, are perhaps being a bit too harsh, here. Cosmic Engineers is certainly a fun enough novel to zip through, one that surely does include some mind-warping concepts and ideas, as well as colorful vistas; a compact and fast-moving (perhaps too compact and fast-moving) affair that is of course required reading for all Simak completists. All others should find it a nonessential but engaging entertainment, at best…

Do you think that he wrote it very quickly? Howlers like “A slinking shape slunk across the dunes” always make me assume the writer is going too quickly, thinking too far ahead of the prose… but like you I do wonder where the copy-editor was.

Some ideas here are really interesting, but I’ll go back to his later work, when he was a little more polished.

Dunno, Marion. I can’t imagine ANY author not rereading and going over his or her work, just to see how the words on the page strike the mental ear. I have no idea what Simak’s work habits were at this early stage, or even at his latter. I guess it’s true what they say about practice, though….