The April issue of Apex Magazine opens with Sigrid Ellis’s editorial, in which she explains that the issue is about repair: “It’s an often-broken world we inhabit. Things falter, plans and bodies and hopes go awry. But we, and the world, keep going. Rebuilt, repaired and reformed. The future will not look like the past. It’s out there, waiting for us, anyway.” They are hopeful words, appropriate to the Easter season, and the fiction Ellis gives us this month is equally hopeful.

The April issue of Apex Magazine opens with Sigrid Ellis’s editorial, in which she explains that the issue is about repair: “It’s an often-broken world we inhabit. Things falter, plans and bodies and hopes go awry. But we, and the world, keep going. Rebuilt, repaired and reformed. The future will not look like the past. It’s out there, waiting for us, anyway.” They are hopeful words, appropriate to the Easter season, and the fiction Ellis gives us this month is equally hopeful.

“Perfect” by Haddayr Copley-Woods doesn’t start out hopefully, though: “Quinn hated everything.” An unhappy soul who includes herself in the everything she hates, Quinn nonetheless attracts would-be friends and lovers in droves, who “mistook her air of biting dislike alternating with weary resignation as intensity, romanticism, and a deep need for help and human compassion.” The one area in which she thrives is science, even though she hates it, too, until she finds it: the perfect equation. The story is a parable, written with charm and grace.

Beth Cato’s poem, “Cogs,” can be read as either a horror or a picture of perfection: a woman becomes one with her sewing machine, her fingers transformed to needles, the chair growing into her flesh, and so on. As awful as that sounds, there is something of grace and beauty to the picture Cato draws as well.

Tom Piccirilli writes about a man who has had to have extensive repairs in “Steel Snowflakes in My Skull.” His head is barely held together, his chest is covered with masks, and he’s still vomiting with disgusting regularity, but he has survived his third death — this one caused by a golf-ball-sized tumor on his brain. The plates in his head are sending out signals, demanding names, holding conversations with other patients, as an orderly wheels him to his room on a gurney. The reader wonders whether the narrator, who calls himself “Tommy Pic” and seems to be the author himself, is having post-operative hallucinations, has entered some strange science fictional realm, or is dead. And only the reader can decide, because Tommy Pic isn’t telling. It’s an odd story, funny on the surface but full of pain beneath. If you know Piccirilli’s personal history, you know that he has had a battle with brain cancer, which makes this story especially poignant.

“The Cultist’s Son” by Ferrett Steinmetz is told from the point of view of Derleth, a young man whose mother was a cult of one, waiting for the coming of a tentacle god who would descend from the sky and wreak destruction. Derleth’s upbringing was unconventional, to say the least; the description of his boyhood is X-rated and not for the faint of heart. Derleth is being romanced by a girl who assumes his upbringing was the same as hers, a more conventional but still extreme Christian upbringing, with her parents telling her the Rapture was due any day and calling her a whore from the time she was 11 years old. “You know what it’s like to live in fear of the world ending?” she asks Derleth. Yes, he does, but the ending he feared was much different from the one she’s talking about. It’s a hard story to read, filled with insanity and violence. The “repair” that follows the tale of Derleth’s life to date seems tacked on, a false note of hope in an ugly, hopeless world. Steinmetz did not go where his story was taking him, probably because, as discussed in an interview following the story, it “depressed the hell out of me when I wrote it.”

“Unlabelled Core c. Zanclean (5.33 Ma)” is a poem by Michele Bannister as told by a rock core that has seen the history of the world. It contains some beautiful images, like the reference to sunken ships “left lyre-boned for the flashing / rhythms of the fish.”

Another poem, “Tell Me the World is a Forest” by Chris Lynch, is a whimsical fantasy featuring forests full of mushrooms and typewriters. It’s in the second-person, always tricky, whether in verse or not, and seems to amount to “Tell me a story.” Again, there’s some lovely imagery (“Tell me someone’s been feeding the typewriters paper / Tell me that in one thousand years / the papermakers will be / priestesses, and all the / temples will be libraries” particularly appealed to me).

Sonya Taaffe’s poem “Aristeia” tells about the Greek gods, beginning with Athene, who sprang fully-formed from Zeus’s forehead “as unbreachable as logic and / beguiling as a myth.” It is a metaphor of wisdom, of life, springing from pain, and unfolds with beautiful economy.

John Chu gives us the story that most clearly represents the theme of this issue, “Repairing the World.” I greatly enjoyed this tale of a world in which other universes break through from place to place and must be sealed off so as not to swallow the world whole. Lila is a graduate student researching a new means to hold the incursions at bay, while Bridger is her linguist, a sort of warrior who fights with the languages of the invading worlds as well as physically. The work is dangerous, but so are some aspects of their own world (Bridger is not free to romantically pursue other men, and Lila is discriminated against because she is a woman). It is the most straightforward, plot-driven story in the magazine; perhaps that is why I liked it the most. But don’t let that fool you: this is a nicely imagined world far different from our own, and the story is completely original. I’d love to read a novel set in this world.

“Juniper, Gentian and Rosemary” is a reprint story by Pamela Dean, about three sisters who work on building a time machine with the neighbor boy, Dominic Hardy. Although all three sisters have designs on him of one sort or another, they fall away as he continues to be interested only in building his machine. He bosses the girls around without mercy, and they all try to please him, but he responds only with more gruffness. When he finally finishes the machine, something strange happens; I’m not quite sure what, but it certainly encourages me to seek out the novel of the same name from which this story was taken.

“After Our Bodies Fail” by Abra Staffin-Wiebe is an essay about the limitations of the human body and the various proposals for repairs made by conmen and serious physicians alike. “Humanity’s history is littered with travesties and adorned with equally stunning triumphs. Our medical history is cut from the same cloth,” we are told, and Staffin-Wiebe gives us plenty of examples.

The magazine also has an excerpt from The Violent Century by Lavie Tidhar, a novel published in the United States only in ebook and audio format (though British hardcover and paperback editions seem to be available if you look hard). It is a story about the World War II, and particularly about the German invasion of what was then the USSR, as well as Fogg and Oblivion, two secret agents with secret powers. It reminded me strongly of Ian Tregillis’s MILKWEED trilogy, which also involved humans with extraordinary mental powers fighting on both sides of the war. Tidhar’s tale is more difficult to assimilate, written with a more difficult structure, making the reader work harder to figure out what’s going on. Whether this ultimately makes for a better book or not is not a judgment I’m willing to make based on an excerpt; but the excerpt certainly whetted my appetite.

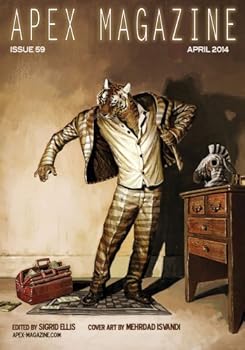

The magazine closes with an interview with the cover artist, Mehrdad Isvandi (and isn’t that cover art, “Time to Be Zebra,” really cool? I like it better than much I’ve seen lately). He discusses his inspirations in the European Orientalist movement of the 19th century, Native American arts and ancient African art.

This is a difficult issue, full of challenging fiction. Ellis perhaps should not have set her readers’ expectations on a theme in her editorial, as the notion of “repair” does not fit several of the offerings unless one uses a shoehorn to squeeze them into that box. Better to have simply said, “Here is some difficult, exciting fiction” and leave it at that, for the stories and poems here are all well worth reading.

Thanks! So glad you enjoyed my tale!