![]() Dark Duets edited by Christopher Golden

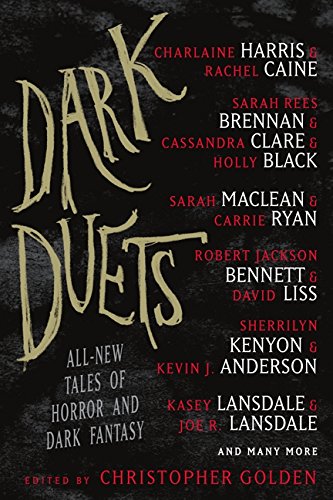

Dark Duets edited by Christopher Golden

Christopher Golden explains in his introduction to Dark Duets that writing is a solitary occupation right up until that moment an alchemical reaction takes place and a bolt of inspiration simultaneously strikes two writers who are friends. Golden has found that the results of collaboration are often fascinating and sometimes magical, as when Stephen King and Peter Straub teamed up to write The Talisman. Writing is an intimate, very personal process, Golden says, and finding someone to share it with is difficult but exciting. Golden therefore undertook to create a book full of such difficult, magical, exciting stories, and Dark Duets is the result.

Many of the stories in this anthology are solid, engaging works. As a general rule, I found the stories in the first half or so of the book to be better than those that came later, suggesting to me that Golden may have used a different structure than the usual one followed by editors in ordering stories. Normally an editor places the best stories at the beginning, the end and in the middle; Golden seems to have started with his strongest stories and worked to the weakest, with a few exceptions.

The anthology begins with “Trip Trap” by Sherrilyn Kenyon and Kevin J. Anderson. A homeless man living under a bridge encounters a homeless family living in their car in a nearby highway rest stop, starting with a little girl’s asking him, “Are you a troll?” In fact, he is — or at least, that’s how he thinks of himself; it’s not clear whether we’re in a fairy tale where trolls eat little girls or the real world where bad men do horrible things to little girls that are almost as bad. Through a sequence of encounters between the family and the homeless man, we’re never sure, in fact, whether “troll” is a metaphor or, perhaps, the reality of a mental illness afflicting the homeless man, or the story’s reality. It’s handled beautifully.

“Welded” by Tom Piccirilli and T.M. Wright is very dark, telling “a familiar story” in which “Kid and girl fall in love. Homicidal maniac kidnaps and butchers girl….” The boy survives the encounter with the serial killer, who staves the boy’s head in to get to the girl. The homicidal maniac is finally caught after nine more murders. He writes to the boy, who writes back, and then begins to visit the murderer in prison. On the day the murderer is to be executed by lethal injection, the boy is there, listening to the murderer whisper exactly what he did to his victims and how they resisted. The boy suffers from migraine headaches, which he often develops on his visits to the prison, and Execution Day is no exception — at least not in that way. But the boy doesn’t just get migraines, and this day is like no other. It’s a haunting story about whether the boy actually survived or is just living — or, perhaps, has been completely transformed by evil into something that is evil itself. This black tale will stay with you for a long time.

“Dark Witness” by Charlaine Harris and Rachel Caine explains those crosses you sometimes see by the side of the road, the ones you think mark the site of an automobile accident where someone’s loved one died. One morning Emma dreams about a pair of crosses and the faceless woman who is planting them as she watches from her car; a handsome man with yellow eyes sits next to her. The horror comes as much — or more — from the presence of that man as from the sight of her name, and her daughter’s, on those crosses. Emma manages to dismiss the dream when she sees two crosses on her way to work, reasoning that they must have triggered the nightmare. That night, Laurel brings friends home for dinner, one of whom is Tyler — the first time a boy has ever made an appearance. Things go well until Tyler catches her alone and asks why she gave him up. This seems like a common tale of a teenage mother who could only manage to raise one child; but that assumes that Tyler and his father are human. Things unravel quickly and horribly. The story ends a little too neatly, but it is powerful nonetheless.

“Replacing Max” is a Weird story by Stuart MacBride and Allan Guthrie. Wesley and his eleven-year-old daughter, Angelina, squabble as they drive about why she has to be with him instead of her mother and stepfather this weekend. There’s something fishy about that, and Angelina senses it, and she pushes Wesley as hard as only an 11-going-on-40-year-old can. It’s snowing and they’re lost when they come across a bed and breakfast that seems like an ideal place to wait out the storm — both the one involving the weather and the one involving their relationship. It helps that the owners of the B&B breed Maine Coon cats; Angelina is fascinated. But things fall apart for Wesley in fairly short order, and it seems he’s likely to get what he deserves. The real question is whether he genuinely deserves what he actually gets.

Gregory Frost and Jonathan Maberry get inside the head of a young woman looking for a good catch among the males in an Edinburgh club on the night before Halloween in “T. Rhymer.” That cute guy over there who’s been giving her the eye all night suddenly seems irresistible, and Stacey finds herself wandering over to him in spite of herself— indeed, in direct opposition to what she really wants to do. Something’s telling her to run, but she can’t. Those golden eyes on him have her in some sort of spell. Stacey follows him out of the club before they even say a word to one another. Fortunately for Stacey, there’s another man watching, and he’s heavily armed with the right sort of weapons for the situation. Those who have figured out the title of this tale know where things go from here, and it’s a fine updating of the old story. And it’s nice to see a woman who acts, rather than merely being acted upon.

“She, Doomed Girl” by Sarah MacLean and Carrie Ryan, is about a woman headed for a Scottish island castle to which she holds the key, crossing the North Sea through a rolling fog. It’s to be a new start for her. But when she gets to her new home, she finds it comes complete with a man demanding to know what she’s doing in his house. A very good looking man, as it turns out, who knows how she came to have the deed and key to the home he calls his own. His mood varies between amusement at her circumstances to cold and demanding that she leave in the blink of an eye. But the ferry she took over was the last of the night and there is nothing else on the island, so she must stay the night. The story has all the trappings of a Gothic romance, which is precisely what this turns out to be. It’s too sappy for my taste, and strikes me as less than original, well-written though it is.

Things pick up a bit again in “Hand Job” by Chelsea Cain and Lidia Yuknavitch, in which we’re once again in Weird territory. One day, the protagonist’s hand starts to speak to her — more specifically, her pinkie finger, which complains about the protagonist’s strictly domestic life. And then physically attacks her. What can she do, as the finger lops off parts of her body? She has to fight back! “Hand Job” is one of the stranger stories I’ve ever read, fulfills the promise of its double entendre title, and is a lot of fun.

“Hollow Choices” by Robert Jackson Bennett and David Liss is as dark a story as I would expect from those two writers. As the story opens, the narrator is leaving prison at long last, but is feeling strangely unjoyful about it. The world outside feels like a foreign country, and it’s just about impossible to find a job. Almost without his willing it, he becomes fixated on a particular woman. “You got the offer and you took it,” he accuses her, and she admits it, saying she’d have been a fool not to. We don’t know for sure what they’re talking about for a while, but the experienced fantasy and horror reader will figure it out. What I find fascinating is how the old tropes play out, and the philosophical discussion of just what happiness means.

Amber Benson and Jeffrey J. Mariotte put their female protagonist through the wringer in “Amuse-Bouche.” She wakes up after a night out to find herself bound, in the dark, and on the verge of complete panic. Her captor, the male protagonist, has created a narrative in his head in which the woman is an actor, and he is shooting a scene. It’s not surprising that he’s gone ‘round the bend, given his upbringing. But this isn’t the standard tale of a vulnerable woman destroyed by a rapacious man; nature also plays a role. The story doesn’t work well, with two first-person narrators in an unconvincing situation.

When I came to “Branches, Curving,” and found that the writing team was Tim Lebbon and Michael Marshall Smith, I was excited: two of my favorite authors working together promised something special. Unfortunately, the story didn’t deliver. Jenni, the protagonist, has been dreaming about a particular oak tree for a long time. She thought it entirely a piece of her dream world until one day she catches a glimpse of it in a random search of the internet. We never learn why Jenni is interested in the tree, though we learn more about the tree. It seems that the authors were searching for bittersweet, but the story never quite gets there.

“Renascence” by Rhodi Hawk and F. Paul Wilson begins in New York in 1878, at a wake for Graziana Babilani. Rasheeda Basemore is the owner of the funeral parlor, an unusual profession for a woman in the late 19th century; but there is more to Rasheeda that at first appears. We get a hint when she appraises the corpse in the same way one might examine a servant or slave, pronouncing her condition “perfect.” Things get even clearer when she sends her assistant out to “fetch us a warm one,” and the assistant asks if he can be the one to “do the ritual.” Sure enough, Rasheeda is a resurrectionist of sorts, bringing select corpses to a sort of life and leasing them for manual labor. Rasheeda must anoint each of these slaves once a month to keep them from becoming berserkers. Things are going well until the wrong corpse is reanimated. It’s a fine, amusing story, carrying a strong flavor of Wilson’s Repairman Jack novels.

The father and daughter team of Joe R. Lansdale and Kasey Lansdale authored “Blind Love,” which was clearly intended to be zany rather than scary. What else could you expect from a story that begins with a way for singles to make a connection that involves merely staring into one another’s eyes? One man mesmerizes every woman who gazes at him except for the first-person protagonist. Which leaves it up to the protagonist, of course, to rescue all the other women from his clutches. It’s a mildly funny tale.

“Trapper Boy” by Holly Newstein and Rick Hautala is set in a coal mining town. John’s father thinks it’s time John started working in the mines, while his mother would like to see him go to school. John himself would like to study to become an artist, but he’s nine years old already, and it’s time for him to contribute to the family’s budget. Mr. Comstock hires John as a trapper for sixty cents a week, working 12 hours each day for six days a week. That means John sits in the dark and cold, waiting to open the mine shaft doors for the mules bringing coal to the surface. Things are looking grim for John until his mother buys him a box of colored chalks, and he uses them while on the job to draw animals on the doors by the light of his small lantern. It seems like a sentimental story until the sharp edges come through. This is one of the best stories in the book, a stand-out in the otherwise weaker second half of the book.

Nate Kenyon and James A. Moore team up for “Steward of the Blood,” in which Christian inherits a substantial property known as Glen Ridge from his grandfather. His grandfather had stipulated that Christian was not to be advised of the death and inheritance until five years after his grandfather’s death. In the intervening years, the house on the estate has fallen into disrepair — in fact, it looks far more decayed than five years should have caused. A letter from his Christian’s grandfather, delivered by Talbot, the executor of his estate, contains directions and strictures on his inheritance, particularly in that it requires that he not leave Glen Ridge again. While Christian is reading the letter, a storm comes up, catching his daughter in the woods, where she is having an odd sort of orientation, a reordering of her world to better align with nature. What lurks in those woods, and how will it affect the family? The reader is not surprised by anything that happens here, for the story is not a new one, though it is well-told.

Michael Koryta and Jeffrey David Greene offer “Calculating Route,” about a GPS that eventually takes its owners to abandoned land originally intended for real estate development before the market collapsed. Several fall victim to the strange machine before we find out what’s behind it. I was disappointed at such a mundane answer to the mystery.

“Sisters Before Misters” by Sarah Rees Brennan, Cassandra Clare and Holly Black is a tale of three witches, one of whom makes off with the trio’s single eye one day when she sees a fine hunk of man. This is clearly another story that is supposed to be funny, but falls short of the mark.

Allan Strand is dying of cancer in “Sins Like Scarlet” by Mark Morris and Rio Youers. He makes it through the days only with the help of liquid morphine, which he carries in a flask. He wants to make peace with his ex-wife before he dies; their marriage had not survived the murder of their only son, who was only seven years old. Allan moved to Canada following his son’s death, but now he is traveling back to England to see Holly, because he has something important to tell her. He moves through not only a fog of pain, but a miasma of self-pity that makes the reader impatient with him instead of sympathetic. It’s a fine trick to pull off, but the authors succeed in making Allan thoroughly dislikeable. Is it because the sin he has come to confess is so dark? It is a finely wrought story, making a strong conclusion to the anthology.

Terry, thanks for the in-depth review. Some of these sound like stand-outs.