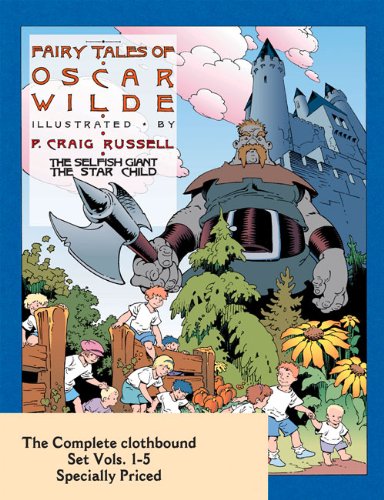

![]() Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Volume 1 illustrated by P. Craig Russell

Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Volume 1 illustrated by P. Craig Russell

Just recently I’ve been reading more comics and graphic novels for kids. As with many of the best young adult novels, the best comics for kids are also of interest to adults. The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde and Jim Henson’s The Storyteller are two collections that certainly fall into this category. This week I’ll review The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, and next week I will review Jim Henson’s The Storyteller. I love fairy tales for a variety of reasons, all of which apply to these books: They tell us about the people who wrote them or the culture out of which they emerged. They entertain us with new perspectives and new or seemingly impossible scenarios and narratives. They offer simple morals. Or they SEEM to offer simple morals, particularly when we hear them as children. Often these same fairy tales convey complex moral, or ethical, lessons to the adults who hear them. And perhaps that’s what I love best about fairy tales: They tell us a lot about ourselves, particularly when we hear anew as adults those very same stories we heard as kids.

I have always loved Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales, and I am very grateful that P. Craig Russell has taken the time to adapt and illustrate five volumes of them. Russell is one of my all-time favorite artists, and he’s in top form here in the two tales that make up the entirety of this first volume. The first story is “The Selfish Giant,” perhaps the most famous of Wilde’s stories. It’s the tale of a giant who doesn’t want to share his garden with the local children. He chases the children off and builds a wall to keep them out. But mean people often learn lessons the hard way in fairy tales as does the Giant in this one. In the end, it’s quite a tender story. If it’s not one you’ve ever read, you are missing out. It’s in public domain, so you can download it right away. However, you’re still going to want Russell’s beautiful interpretation of it.

Russell does an equally impressive job with “The Star Child.” This story has a moral to it as well, but this time, the moral is taught to a child instead of to a mean grown-up. Pairing these stories together makes for an important mutual message about the need for those of all ages to practice kindness. In “The Star Child,” a poor man discovers an abandoned boy and raises him along with many other children. This “Star Child,” who seems to have come from the sky, is the most beautiful boy anyone has ever seen. However, as in The Picture of Dorian Gray (Wilde’s only novel), this youth’s beauty hides an ugly and vile inner nature: The Star Child throws rocks at the poor and at the deformed, and he mistreats all who are not in his immediate circle of bullies. He will not listen to the advice of his adoptive parents or any other adult. When not being mean to others, including the creatures of the forest, he looks into a pond and, like Narcissus, enjoys lovingly gazing at his own image. Of course an event occurs that causes this young bully to seek to amend his ways, and his journey of redemption is much longer and complex than the giant’s in the previous story. It, too, is a wonderful moralistic tale, and in some ways, I like it better than “The Selfish Giant,” but in the end, they are equally compelling stories.

Russell does an equally impressive job with “The Star Child.” This story has a moral to it as well, but this time, the moral is taught to a child instead of to a mean grown-up. Pairing these stories together makes for an important mutual message about the need for those of all ages to practice kindness. In “The Star Child,” a poor man discovers an abandoned boy and raises him along with many other children. This “Star Child,” who seems to have come from the sky, is the most beautiful boy anyone has ever seen. However, as in The Picture of Dorian Gray (Wilde’s only novel), this youth’s beauty hides an ugly and vile inner nature: The Star Child throws rocks at the poor and at the deformed, and he mistreats all who are not in his immediate circle of bullies. He will not listen to the advice of his adoptive parents or any other adult. When not being mean to others, including the creatures of the forest, he looks into a pond and, like Narcissus, enjoys lovingly gazing at his own image. Of course an event occurs that causes this young bully to seek to amend his ways, and his journey of redemption is much longer and complex than the giant’s in the previous story. It, too, is a wonderful moralistic tale, and in some ways, I like it better than “The Selfish Giant,” but in the end, they are equally compelling stories.

The Irish author Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) is a fascinating man to study. For two primary reasons, his life offers a seemingly strange contrast with the moralistic material he wrote, and I want to mention them here as potential reasons why we don’t hear of these fairy tales in the same breath as THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA, as I think they should be.

First, Wilde often made contradictory aesthetic claims. And these claims are not only contradictory in themselves; they are also contradictory — in some sense at least — to the moralistic stories he often wrote, particularly in The Picture of Dorian Gray and fairy tales such as “The Selfish Giant” and “The Star Child.” In the Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde wrote that “All art is quite useless.” Wilde clearly was reflecting the attitudes of his fellow writers and artists who, influenced by the French, argued provocatively that Art should be done for no reason but for itself, or what is known more concisely as “Art for Art’s Sake.” This aesthetic philosophy surely appealed to Wilde for a variety of reasons that I won’t reflect on here, and though his saying that “All art is quite useless” can be interpreted in several ways, we can’t get around the fact that Wilde wasn’t just a little bit didactic and moralistic in his fiction; he was just as extremely didactic in one direction as his aesthetic theory was in the other in claiming for all art a lack of rhetorical intention and purpose. I can only assume that Wilde found joy in such contradictions, as did another great contradictory author — Walt Whitman — who, like Wilde, found beauty in the male form AND celebrated the nature of contradictions: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.”

Wilde was both extremely famous AND infamous, and he ultimately suffered greatly from mistreatment at the hands of the man he loved — Alfred Douglas — who used his forbidden love with Wilde as a weapon in his long battle with Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry. Wilde was sacrificed to this young man’s vanity and immaturity: Douglas encouraged Wilde to enter into a trial with Queensberry that could have been avoided and was impossible for Wilde to win. The result was that Wilde spent a very rough few years in prison and deteriorated physically rather rapidly: He was released in 1897, went into exile in Paris, and died only a few years later. He didn’t just write about contradictions; he lived a life of contradictions as did many gay men of his time, and unfortunately he became a cautionary tale to other gay writers at the end of the century, including Somerset Maugham and E. M. Forster (whose explicitly gay novel did not come out until 1971(!), safely after Forster’s death). Gay men were shown very clearly what society thought of homosexuality.

Wilde was both extremely famous AND infamous, and he ultimately suffered greatly from mistreatment at the hands of the man he loved — Alfred Douglas — who used his forbidden love with Wilde as a weapon in his long battle with Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry. Wilde was sacrificed to this young man’s vanity and immaturity: Douglas encouraged Wilde to enter into a trial with Queensberry that could have been avoided and was impossible for Wilde to win. The result was that Wilde spent a very rough few years in prison and deteriorated physically rather rapidly: He was released in 1897, went into exile in Paris, and died only a few years later. He didn’t just write about contradictions; he lived a life of contradictions as did many gay men of his time, and unfortunately he became a cautionary tale to other gay writers at the end of the century, including Somerset Maugham and E. M. Forster (whose explicitly gay novel did not come out until 1971(!), safely after Forster’s death). Gay men were shown very clearly what society thought of homosexuality.

So why do I bring up Wilde’s aesthetic theory and his homosexuality in a review of a graphic novel adaptation of his fairy tales? I do so for several reasons. First, I think Wilde’s explicit aesthetic theory and association with the art for art’s sake movement leads us to not categorize him as a moralizing writer of fairy tales (which he is). Secondly, I think calling attention to his famous trial and imprisonment points out why many Christians (not all) have been hesitant to associate this famously homosexual author with the Christian writing of C. S. Lewis. I do want to be clear: I am not making any claims here about all Christians viewing homosexuality in a certain way. However, I don’t think anybody would argue with my assertion that between 1850 and 1950 Christians were seen as frowning upon the practice of homosexuality. To summarize, his being remembered for his homosexuality along with his aestheticism has prevented him from being seen as the great Christian moralist he is, at least in these fairy tales.

Rarely do I take this long of a detour in my reviews, but I believe this one is essential for appreciating “The Selfish Giant” and “The Star Child.” Why? Because both have Christ-figures in them in a way that is quite astounding. The Christian imagery is not subtext. It is not subtle. It is explicit. In fact, in one story (I won’t tell you which), the Christ-figure isn’t even a figure as one thinks at first — he actually IS Christ! The other story is equally Christian. Having grown up in a Christian church and as a member of one now, I don’t think I could count the number of times I’ve been asked if I’ve read C. S. Lewis‘s writing, from his Christian fantasy fiction for children (NARNIA) and for adults (THE SPACE TRILOGY) to his Christian non-fiction (Mere Christianity) and creative essays (The Screwtape Letters). However, never once in my entire life have I been asked in a Christian context if I’ve read Oscar Wilde’s Christian fiction. But I’m beginning to think that Wilde deserves consideration as a Christian writer, at the very least for these two fantastic stories. There are four more volumes of Wilde’s fairy tales as adapted by Russell, and I look forward to reading them. Since I haven’t read these stories in over twenty years, I’m particularly interested to see if any other stories fit into the category of “Christian fairy tale.” But either way, look for a review of those volumes in the future.

I hope you order a copy of volume one. It’s a beautiful book that looks great out on a table. And I hope you read more Oscar Wilde. As I’m sure you can tell, I’m a big fan of his. His great wit continues to be praised to this day, and I would place him high on my short list of answers to that question we have all answered at one time or another: “If there were one dead person you could bring back to life and with whom you could spend one day in conversation, who would it be?” You know exactly why I long to converse with this man if you’ve ever read or seen a performance of his fantastic play The Importance of Being Earnest. His other plays are also worth seeking out, as is his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, his poetry, his essays, and of course the fairy tales. This man wrote plays that make us laugh so hard we no longer feel the weight of life, but in his poetry, he cried out about the pain that hurts all of us the worst, the pain inflicted upon us by those we love, the pain that we in turn inflict upon those we love. How can you not read fairy tales written by a man capable of writing these following lines about being put in jail by the person he loved?

And all men kill the thing they love,

By all let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

I am the chaplain of a small, Methodist college in Kentucky, and your fascinating review has prompted me to buy a copy of this book for our Spiritual Life Center. Thank you so much.