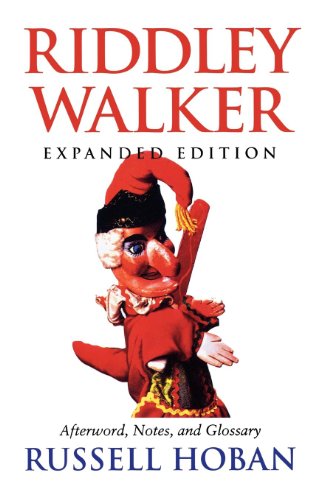

![]() Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

[At The Edge of the Universe, we review mainstream authors that incorporate elements of speculative fiction into their “literary” work. However you want to label them, we hope you’ll enjoy discussing these books with us.]

Language is dependent on the society that uses it. We weave into our idiom words and phrases that explain our history and our present. Similes and metaphors embed themselves so deeply into our sentences that we don’t even notice them. Some are slang: we didn’t get the memo, we watch situations go sideways and we compare apples to apples. Some are beyond slang. Fifteen years ago no one would have “texted” a friend, but they would have “okayed” a plan without thinking twice. Language is dynamic, fluid, responsive and reflective, changing constantly.

Take this concept, conjure a society thousands of years after a world-destroying thermonuclear conflict, write in the language of the survivors, and you have Russell Hoban’s 1980s masterpiece, Riddley Walker.

This book won the 1982 John W. Campbell award. The narrator is Riddley Walker. He grew up in a clan of people who forage metal, broken machinery and other goods from the ruined towns and cities. He shares the valley in central Inland with the formers, who grow crops and raise goats and sheep, and the chard coal burners in the forest. The Pry Mincer and the Wes Mincer, from the Ram, govern via a series of Punch-like puppet shows called Eusa shows. People function at an Iron Age level, using spears and bows and arrows, running from the feral dogs that hunt them. “Dog et” is a common cause of death in Riddley’s world.

Riddley is in line to become his people’s connexion man, who speak after the Mincery men put on their “Eusa shows.” Eusa is a powerful and mysterious character, a symbol of the Puter Leat and the Power Leat. It is he who split the Littl Shynin Man called Addom. He “run them through the Power Ring he mayd the 1Big1. Eusa put the 1Big1 in barms then him and Mr Clevver they droppit so many barms they kilt as menne uv thear oan as thay kilt enemes. Thay wun the Warr but the lan wuz puyzen from it the ayr an the water as wel.” Eusa may represent the nations or governments who started the war, but he is also St. Eustace, whose life is depicted in a 15th century wall painting in Canterbury Cathedral — or, as it is called in Riddley’s day, Cambry. Cambry is the senter of the Fools Circel 9ways, and when Riddley visits it, it is plainly a particle accelerator, as described in one of the folktales.

“They bilt the Power Ring that’s where you see the Ring Ditch now. They put in the 1 Big 1 they woosht it aroun there came a flash of lite then bigger nor the woal worl and it ternt the nite to day.”

Riddley has always had a strange mystical bent. During his first connexion, he shifts into a “trants,” speaking words his people don’t understand. Only a few days later, after his father’s death, Riddley discovers an old Punch puppet. Soon his people have driven him out and he is “roading,” accompanying a pack of killer dogs.

Riddley explores the dead towns and encounters the “Eusa people;” genetic mutations kept as slaves, bred and ritually tortured by the men of the Ram, a gruesome payback for the war. He experiences Cambry, and he discovers the truth hidden in his language, the Eusa plays and children’s rhymes. Coded into the folk tales and the rhymes is the recipe for the 1 Little 1 –not atomic power but gunpowder.

Hoban writes the entire book in Riddley’s language. Sometimes the language tells stories; sometimes it is purely poetry. From our vantage point now, the world building has a few gaps. Riddley’s people barter rislas (cigarette papers) and a substance called hash that they smoke for relaxation. It’s hard to believe anyone would ever be able to grow opium poppies in England, and particularly not in the climate described by Hoban. Abel Goodparley, a shadowy, villainous character, explains to Riddley that the Ram has been counting years since 1997, the last date they’ve found from “time back way back,” and they’re at around 2300. At first that seems outrageous. Thinking of the 1970s, though (Hoban began writing this book in 1974), nuclear annihilation was the overwhelming fear of the time. The mutants, the “Eusa people,” even though they are not particularly plausible in many ways, are powerfully symbolic of this fear. Riddley even comments on this to Goodparley, asking, if the folks from time back way back had boats on the air and pictures on the air in 1997, why, in 2300, do his people still live in the mud. This was the nightmare: earth, water and air poisoned for so many generations that civilization dies.

I read the Indiana University Press expanded edition, which has notes from Hoban and a picture of the painting of St Eustace. You can see the elements Hoban wove into his book. It’s also fascinating to see that he started the book in Standard English, and finally distilled it down to the language of Riddley’s people.

Riddley does not directly change his world, but he does indirectly. He walks out of his own history into myth, carrying a puppet that pre-dates the figures of the Eusa shows, with a pack of killer dogs and a group of human followers. Hand-and-hand with the rediscovery of gunpowder, Riddley delivers new stories. Read it slowly — you’ll have to. Read it aloud when you can. Riddley Walker is riddled with mysticism and mystery; and its language is the story.

great review of a true classic Marion. Yep, read it slowly for sure (and I found, be prepared to stop, think, reread, think, read more slowly). And aloud as well. A tough book to read but worth it. Thanks for giving it such great attention!

Bill — I also found I was re-reading and re-thinking as the story unfolds and you start to see the layers.

I’m finding the diction really interesting, reading your review. I bet it takes a while to get used to but really helps set the scene.

I read Riddley Walker, an amazing book, back when it came out and have read it many times since. One of my all time favs. Recently, I started The Cloud Atlas, by David Mitchell, and was surprised to find one section (the book has 6) to be so much like Riddley Walker in the character’s language. Was Mitchell merely giving a nod to Hoban, a true master, or doing a really bad imitation? I’m puzzled. Mitchell’s book, otherwise, is ambitious, engrossing, and highly entertaining. A movie based on it is coming out soon. Has anyone else read it?

Mitchell’s thing is playing with voice, and given that he’s on record as admiring Riddley Walker, I suspect he wanted to do something similar. Its similarity did make me a bit uncomfortable, and it isn’t as good as Hoban, but I still enjoyed it. Incidentally, Alan Moore does something just as remarkable with voice in his first chapter of The Voice of the Fire, in his case from the viewpoint of a Neolithic teenager.

It’s on my list, Gloria, but I haven’t yet. I think Bill C has.

Kelly, it takes a few pages, but it’s amazing how quickly the human mind does adjust.