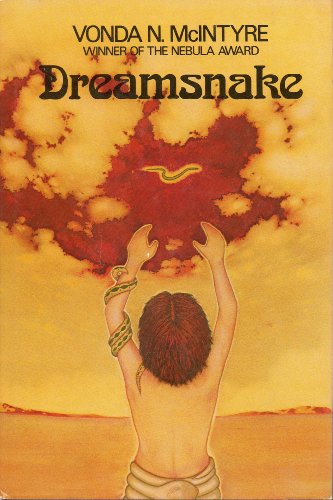

![]() Dreamsnake by Vonda N. McIntyre

Dreamsnake by Vonda N. McIntyre

Dreamsnake (1978) by Vonda N. McIntyre is a novel that won the Nebula and Hugo double, something that happened more often than not in the 1970s. Although slightly less common since the mid-1980s, it is still surprising to see how many novels are joint winners, especially since the nominees don’t overlap that much. I purchased Dreamsnake as an e-book after reading an article by Ursula K. Le Guin about it. It ended up on the formidable to-read stack but this month I finally managed to read it. Like Le Guin, I’m a bit surprised this work isn’t better known. It’s a very nice piece of writing and it has aged a lot better than some of its contemporaries. It has some flaws as well, though.

Set in a post-apocalyptic world, Dreamsnake follows the travels of the healer Snake. With the help of three genetically modified snakes, a small group of healers tries to see to the healthcare of as many people as possible. In many places, society has fallen from a high-tech one to very basic patterns of existence. With the re-emergence of these ways of life, a lot of superstitions about things like inoculations have returned and Snake’s tools of the trade are viewed with a mixture of fear and distaste. When Snake loses the most precious of her three snakes — the Dreamsnake, the one who can comfort those with no hope of survival — she is severely handicapped. Returning to the healers’ main settlement is not an option, Dreamsnakes don’t breed well, and there is simply no replacement. A long hard search for a new source of these valuable animals begins.

What struck me most about Snake is that she is a very compassionate person. Her need to help people goes beyond healing the sick and wounded. She meets a number of characters who face personal problems caused by cruelty, cultural peculiarities and the fact that a lot of people live in small, isolated communities. She often considers helping these people at her own expense and some of these decisions have drastic consequences. One of the secondary characters thinks she is naive and too trusting and there is more than a bit of truth in that. She is, however, in a perfect position to show us the workings of the various cultures she encounters. To some of them Snake is a frightening figure, able to control animals most people have an innate fear of. The original story this novel is based on, a short piece that is now the first chapter and was published in Analog in October 1973 under the title “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand,” very effectively shows what kind of suspicion and fear she is up against.

Snake may be compassionate, but there are some things that anger her greatly and a few characters get a taste of her anger. The abuse of the supremely valuable Dreamsnake venom is probably what angers her most. Snake appears to have a mild personality when we first encounter her, but as the novel progresses she shows her fierce side, as well as a determination to achieve the goals she thinks are essential. Snake is not a kick-ass heroine in the urban fantasy mold that is so popular at the moment, but in a slightly understated but nonetheless formidable way.

The setting of Dreamsnake is almost fantasy-like. Although remnants of a more advanced civilization show up, and the alien origin of Dreamsnakes is mentioned, much of the story is set in low-tech environments. Some references are made to genetics but other than that, there isn’t a lot of hard science in the novel. I think this is one book that would go down well with people who prefer fantasy over science fiction. What actually caused the downfall of civilization remains unknown, but to the story that doesn’t matter all that much. Snake is trying to make things better in a small way, not trying to reinvent the ancients’ civilization.

One thing most of these cultures share is a different view on sexuality and reproduction. People are able to regulate their own fertility, which changes the way they think about sex. Long-term relationships are formed, of course; something akin to marriage exists. Sexual desires are considered a normal human need, however, and so relief of sexual tension in more casual relationships, both homo- and heterosexual, is not frowned upon. The gender of one character is left for the reader to decide on, which is a nice touch.

Control over fertility is one way in which the advanced biological knowledge that lingers in this destroyed world becomes apparent. For the real hard science fiction fan, the absence of a reason why so much knowledge in this particular field remains may be a bit frustrating. There are some vague references to communities with even more advanced technology and a few to people or at least sentient beings living off-planet, but Snake’s view of the world, and therefore the reader’s, is far from complete.

I liked Dreamsnake a lot; the writing, characterization and setting are all very well done. I can’t quite shake the feeling that the premise of the novel is a bit flawed, that the value of the Dreamsnake is way overrated. It neither cures nor kills. In effect, it eases the suffering of those for which no treatment is possible any more. That is important, of course — nobody likes to see their loved ones suffering — but curing people is Snake’s trade. She feels much more handicapped by the loss of the Dreamsnake than one would expect. In fact, at one point in the novel, she does find a way around the loss, although one that’s not as humane as she would have liked. The novel gets a lot of things right, but the foundation seems shaky. That being said, less deserving novels have won the Nebula or Hugo. Dreamsnake is well worth reading.

That is one seriously seventies cover.

Hehe, the edition I read had a different cover. I think I prefer that one.

Mine had a different cover too. I thought the importance of the dreamsnake (and Snake’s discovery) was about how the snakes reproduced. In that sense, the ability to breed more snakes and get more pain-reducing venom, her discovery toward the end was quite important.

It’s more the matter of why she feels so hamstrung without a Dreamsnake that escapes me. Humanity has never had problems finding narcotics after all.