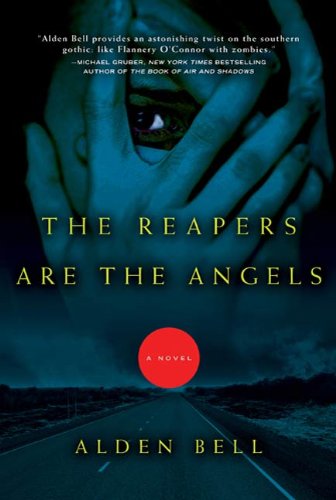

The Reapers Are the Angels by Alden Bell

The Reapers Are the Angels by Alden Bell

What does the United States look like 25 years after zombies have led the nation into an apocalypse? What is life like for a teenager born ten years or so after the apocalypse? What has she seen, and done, and what is the state of her soul? These are the questions first-time novelist Alden Bell attempts to answer in The Reapers Are the Angels, a soul-searing novel that looks at some of life’s hardest questions through the lens of violence so common and natural it isn’t even evil.

Temple is fifteen year old, and she knows that there is a God, and a slick one at that. She knows because of all the miracles that can still be seen in the world, like tropical fish dancing around her feet, “All darting around like marbles in a chalk circle, and they were lit up electric, mostly silver but some gold and pick too. They came and danced around her ankles, and she could feel their little electric fish bodies, and it was like she was standing under the moon and in the moon at the same time.” A little miracle, but enough of one that Temple is cheered. This is some mighty fine writing: Bell has sketched Temple’s character for us in just a few lines. He tells us about the world next, a world that “has gone to black damnation,” and the quickly, we know we’re in a post-apocalyptic America, one where “meatskins” keep coming at the living until their brains are put out of commission.

At the beginning of The Reapers Are the Angels, Temple is living in a lighthouse on an island off the coast of Florida, eating fish she catches herself and pignuts she finds in the underbrush. She’s living in a kind of paradise, with no clear threat, but also no company. As the season starts to change, though, the shoal between the island and the mainland is getting bigger, and one day a zombie shows up — in bad enough condition that Temple easily dispatches him, but as a clear sign to her that it’s time to move along. And so begins Temple’s adventure in what used to be the southern United States.

Surprisingly, much still works in the world that is left over after the zombies have ravaged it. Operable cars can still be found, and gas stations still yield gas; cities still have lights and water, apparently without anyone attending the utilities. It’s a bit of fantasy that lets this book work, though this underlying irrationality niggles at the mind. It means that Temple can move from oasis to oasis, finding the communities that have formed for mutual protection all over the country. Each oasis has its own dangers, though, for the living have always been nearly as dangerous as the dead of this world. Temple is able to meet the dangers from both the living and the dead, with a violence that seems foreign to the girl we meet by eavesdropping on her thoughts — a violence we cheer, because we like Temple and she won’t survive without that very competent way she has with a gurkha knife.

Before long, Temple is fleeing from Moses, a living man with a grudge, accompanied by Maury, a mentally deficient man who seems much like a living zombie, unable to speak, apparently with little mental capacity, but a peaceful man. Temple wants to stay alive and find Maury’s relatives to hand him off and be on her way to Niagara Falls, which she’s heard about from an older man who once saw the Falls and tells her about how miraculous they are. Finding miracles seems to be Temple’s calling, and she finds them everywhere, even as she is attacked again and again. She never holds it against those who attack her; it is simply the way of the world.

This is one of the oddest and best zombie novels you will ever read. The focus isn’t on the zombies at all, but on surviving in a world where zombies have come to exist. (Their genesis is never explained.) In fact, it’s about more than surviving; it’s about truly living in this world, seeing its beauties wherever they might be. In some very strange ways, this book is almost a prayer of thanks for all that remains when the worst has happened. You’ll think that that is a strange reaction to this book when you start reading it, but as the pages fly by, and when you reach the end, you’ll realize that a blue sky looks more beautiful than before; and you’ll think about how wonderful it is that you can read, that you can sit peacefully by a still lake, that the Grand Canyon exists, and you will realize that Alden Bell has touched your deep heart’s core.

~Terry Weyna

Alden Bell’sYA post-apocalyptic fantasy novel The Reapers Are the Angels shares DNA with Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Both books deal with the same theme: how to maintain humanity in the face of complete devastation. The apocalypse in Bell’s book is a mysterious zombie plague, which probably means most English professors won’t be adding it to their reading lists. That’s a shame, because The Reapers are the Angels has a lot to say about the human condition, connections, compassion, and hope.

Alden Bell’sYA post-apocalyptic fantasy novel The Reapers Are the Angels shares DNA with Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Both books deal with the same theme: how to maintain humanity in the face of complete devastation. The apocalypse in Bell’s book is a mysterious zombie plague, which probably means most English professors won’t be adding it to their reading lists. That’s a shame, because The Reapers are the Angels has a lot to say about the human condition, connections, compassion, and hope.

Temple, Alden Bell’s fifteen-year-old female protagonist, was born well after the sudden irruption of zombies twenty-five years ago. She has been on her own for quite a while. When the book opens, she is living in a lighthouse on an island off the coast of Florida. A zombie washes up on shore, so Temple decides it’s time to move on.

Back on the mainland, Temple easily evades the “slugs” or “meatskins” who shamble around the shore, finds a car with fuel in the tank, and heads north. This gives Bell the opportunity to show us a country in ruins, with abandoned cities, derelict vehicles and random convenience stores that still hold packages of neon-orange cheese crackers, a treat Temple loves. Temple soon finds a community barricaded in a high-rise building in a city. It looks as if she will be able to stay there for a while, but things turn bad. A fellow outsider assaults her and she fights him off, killing him in the process. His brother, Moses, swears vengeance against her. With the help of a woman in the community, Temple takes a car and flees west.

On the road, Temple connects with another man, Maury, who is either autistic or severely developmentally delayed. With Moses in close pursuit, Temple and Maury drive across the southeast, heading west to Texas. Along the way, the reader sees through Temple’s eyes the various stratagems humans have used to rebound from the zombie disaster; communities like the first one, trying for a pre-zombie normalcy; an estate with a family acting out a fantasy of genteel southern life; and isolated humans who have used the excuse of the plague to indulge in the worst atrocities, rationalizing that God has given them this right.

This world is tragic and horrifying, but Temple doesn’t judge. Imagine if you had been born in Kosovo just after the civil war started; the only frame of reference you would have for life would be a war zone. Temple does not even judge the slugs, seeing them as animals, not God’s curse or evil beings themselves. Temple’s spirituality, on display from the first page of the book, does not spring from any particular ideology or teaching; it almost seems innate. In this horror of a world, Temple sees God and wonder everywhere, even when she is locked in a cell in a torture chamber.

The book contrasts Temple with her pursuer, Moses. Moses is old enough to remember the world before the plague, and this seems to inform the bloodstained code of honor that he holds. Even though Moses acknowledges that his brother did wrong, that fact will not stop him from killing Temple if he can.

If the book has problems, it is with the world-building. Twenty-five years is time enough for a government and infrastructure to have re-emerged, and things like gas stations with “pumps that still work” and random locations with electricity seem just too convenient. I was willing to overlook the illiterate Temple’s prodigious vocabulary for two reasons; first, because as a southern girl she comes from a long and honorable oral tradition; and second, because there’s an implication, subtle but definite, that her illiteracy is the result of brain function, not poor education, since Temple may be something more than a regular pre-apocalypse human.

I have more trouble with Temple when she seems to draw on experiences she could not have had. Why would she know what a ventriloquist’s dummy looks like? On the other hand, I firmly believe that processed cheese crackers would last well into the next century.

Bell’s exquisite prose helps smooth out the wrinkles as well. Whether it’s dialogue or narrative, Bell weaves a shimmery carpet of words, whether beautiful, terrible, or both:

Mississippi is one of the words she recognizes when she sees it. All the squiggles in a row, separated by the vertical lines. She sees a sign that says Mississippi on it and it doesn’t surprise her. Along the roads the trees have been overpowered by kudzu, like a blanket of green tossed over all the shapes of the earth. Driving through small towns, she finds canted treehouses with rotted doors, plastic slides toppled over on front lawns, whole communities gone dense with the smells of honeysuckle and verbena. Elsewhere, on rolling stretches of back road, desolate plantation land has long ago gone back to wildflower and weed, grazed over by riderless horses traveling in packs and mewling cows standing silhouetted on the hilltop horizons.

In The Road, the boy says to his father, “We’re the good guys, right?” In The Reapers are the Angels, Temple asks, “Am I evil?” In each book, characters wrestle with the gap between survival-based behavior and moral behavior. Is it possible to have morality, community, connection, when you are fighting for survival? The father in The Road, and Moses in Reapers, would give you one answer. Temple would give you another. Who is right? The Reapers Are the Angels will help the reader decide the answer to that question.

~Marion Deeds

This is one of my absolute favorite books.

This book sounds great!

With both you and Marion giving it rave reviews, I simply must read it!

I’m so glad you mentioned Bell’s exquisite prose. You know, I just read a book by his wife, Megan Abbott, and she is an excellent stylist also (and a good story-teller). To borrow a “soap-opera” expression, they’re a literary supercouple.