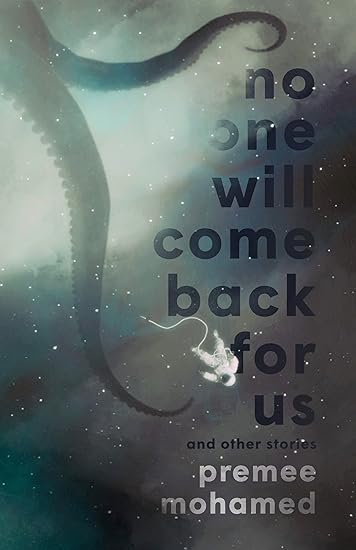

![]() No One Will Come Back For Us by Premee Mohamed

No One Will Come Back For Us by Premee Mohamed

Premee Mohamed is one of the best writers around, and her first short story collection, 2023’s No One Will Come Back For Us is a great way to get to know her work. Seventeen stories give a good overview of her style—I should say styles, because she’s versatile—and her themes. If you like Lovecraftian elder gods, alternate history, dark science fiction or gothic tales set in elegant, decadent worlds of decay and corruption, check this one out.

Here’s the Table of Contents:

“Below the Kirk, Below the Hill” — A lighthouse keeper adopts a dead girl she pulled out of the water, but “dead” isn’t quite what we consider dead. The girl’s biological family might want her back—and so might the small gods of the ocean from which she was pulled.

“Instructions” — During wartime, decorum is more important than ever for a British soldier, even when the enemy isn’t… quite like us.

“The Evaluator” — Contamination can affect the ground, the water, the plants, people and gods. It takes an evaluator to determine just how serious the infestation is, and sometimes it’s serious indeed.

“At The Hand of Every Beast” — An old man and a young boy try to survive an attack by an ambulatory cathedral.

“The Adventurer’s Wife” — Written in the style of H. Rider Haggard or Arthur Conan Doyle, this story explores the abrupt death of a British explorer, returned home after a strange incident in Africa.

“The General’s Turn” — In a country perpetually at war with somebody, a military leader plays a traditional and vicious game with a captured soldier. When Death takes a turn, things go sideways—almost literally.

“Sixteen Minutes” — A Cold War chiller featuring a bomb shelter, a rat and a man with a guilty conscience. This chilling piece would have made a fine Twilight Zone episode.

“Fortunato” — The attempt to colonize the planet failed, but the descendants don’t want to leave yet. How has Fortunato changed them?

“The Honeymakers” — A strange and lovely gothic story about girlhood, goddesses and bees.

“Four Hours of a Revolution” — In a war-torn city, a philosophical Death follows a squad of revolutionaries on what seems to be a suicide mission.

“For Each of These Miseries” — A scientist grapples with ancient monsters in an undersea fortress, in a story Mohamed defines as a genderswapped retelling of Beowulf.

“Everything as Part of Its Infinite Place” — A mind-bending multiverse story of math and sacrifice. Yes, you read that right; math and sacrifice.

“No One Will Come Back For Us” — After the occurrence of a Dimensional Anomaly, a journalist follows a group of doctors tracking a new disease in rural Africa. This new world is not a safe place.

Premee Mohamed

“Willing” — Families love one another, and gods expect their due. In this vivid story, those two facts clash, leading to a father’s terrible and loving choice.

“Us and Ours” — Set in the same world as “Willing” and “The Evaluator,” teens from a small town join forces with other townspeople, as the small gods fight to preserve their territory from the Old Ones.

“The Redoubtables” — A young journalist tries to interview the survivor of an extraordinarily destructive incident, to get to the truth of what caused it. This story is a study of evil.

“Quietus” — In a different way, this story is also a study of evil, as a military volunteer suffers through an experiment in unihemispherical sleep. This is a real thing—some animals can put half their brain into a mode of sleep. Humans cannot, and that’s the basis of this quietly relentless horror story.

This collection contains two of my sentimental favorites. I first read “Willing” in an edition of Third Flatiron, Principia Poderosa, and I was blown away. In a world with small and not-so-small gods, deities demand their due, and it isn’t a good idea to deny them. Arnold and his wife love their late-in-life daughter Clover. Arnold likes his hard life on the prairie, making a go of farming, but their peace is shattered when Clover gets a summons. She’s been chosen for a sacrifice. Arnold and his wife must make a desperate decision. I was blown away by the prose of this story when I first read it, from the concrete, realist opening as Arnold deals with two cows who are calving at the same time, in the middle of a storm. The tale pivots on a bit of rural folklore I heard growing up. Years later, I am in just as much awe of the sparse, elegant prose that depicts a hard birth in a barn and a father’s love for his child with equal precision.

My second sentimental favorite is “The Adventurer’s Wife,” largely, once again, for the style. It’s a perfect pastiche of the late Victorian/early Edwardian “weird” adventure story, told in the first person by a young reporter sent to interview the dead adventurer’s widow, who was a surprise to everyone. The reader will start “reading between the lines” pretty quickly, but our thick-headed reporter doesn’t see the truth until it’s just a bit too late.

“Instructions,” is also a pastiche—a re-creation of the kind of instruction booklet soldiers might have really received as they occupied enemy territory. Gradually, the instructions make it clear that the “enemy” is not exactly what we expect. “Instructions” is a short, creepy, funny treat.

In “For Each of These Miseries,” a scientist fights creatures… monsters?… far beneath the sea. When I say this story felt cinematic, I mean it as a compliment. The underwater Oceanic Tower is not being maintained, and it sits close to an extrusion that looks almost like a building. The staff and crew are on edge, and in the middle of Gene’s introduction (she’s shortened her birth name) the tower is attacked by a creature that should not exist. There are monsters outside, secrets inside, and just enough action to keep me on the edge of my chair.

“The General’s Turn” felt as if it could slide easily into the cynical, decaying world of Mohamed’s novella And What Can We Offer You Tonight. The rotting aristocracy of a belligerent nation (who just may be losing this particular war) torture a captured soldier with a “game.” Players, draped in faded silks and rotting velvet, stand at various points around an intricate horizontal clock. The clock still runs. Each aristocrat plays a part, and one part is Death. The soldier must correctly identify Death before the ticking runs down and a bell sounds his death knell. He must also dodge a more immediate death beneath the rotating cogs. The story is nearly hallucinatory, with a gripping cat-and-mouse game between the prisoner and the master-of-ceremonies, Vessough. He is our first-person narrator, and spends much of this increasingly tense work rationalizing how it’s not cruelty, it’s tradition. This is a deeply disturbing, exquisitely written story, and a masterclass on rising tension.

“Four Hours in a Revolution” follows a group of revolutionaries who don’t know they’ve been infiltrated by a government mole. Like in “The General’s Turn,” Death is a character—in fact, our narrator. However, there is more than one Death in this world. The story is suspenseful, and while the world isn’t a perfect fit with “The General’s Turn,” there are echoes and weird reflections of it as the revolutionaries advance.

“The Evaluator” and “Us and Ours,” inhabit the same universe, where a war between the Elder Gods and the “small gods of hill and green,” is waging. Like “Willing,” “Us and Ours” explores the nature of sacrifice and the power of community. “The Evaluator” read more as growing horror, as the dread of the circumstances our bureaucratic narrator investigates grows deeper and stranger.

Read “At the Hand of Every Beast,” simply for the prose, and that nightmare image of a hungry walking cathedral.

While these were my favorites, every one of these stories is well thought out and beautifully written. It’s a good sampler of Mohamed’s work, or just a chance to consume some shivery, creepy horror.

It would give me very great pleasure to personally destroy every single copy of those first two J. J. Abrams…

Agree! And a perfect ending, too.

I may be embarrassing myself by repeating something I already posted here, but Thomas Pynchon has a new novel scheduled…

[…] Tales (Fantasy Literature): John Martin Leahy was born in Washington State in 1886 and, during his five-year career as…

so you're saying I should read it? :)