THE ORPHAN’S TALES by Catherynne M. Valente

THE ORPHAN’S TALES by Catherynne M. Valente

I haven’t read any fantasy quite like Catherynne M. Valente’s The Orphan’s Tales duology. This is the story of a young orphan girl who is shunned because of the dark smudges that appeared on her eyelids when she was a baby. She lives alone in a sultan’s garden because people think she’s a demon and nobody will claim her. However, one of the young sons of the sultan, a curious fellow, finds her in the garden and asks her about her dark eyes. She explains that there are wonderful stories written on her eyelids and that a spirit has told her she must read and tell the stories; Then the spirit will return and judge her. The prince loves stories, he begs her to tell him one, and so she begins.

The rest of In the Night Garden and its sequel In the Cities of Coin and Spice is a collection of nested stories that are interspersed with short interactions between the young prince and the girl with the dark eyes (somewhat like The Arabian Nights). These stories are all connected to each other, but each is unique and highly imaginative. There are fascinating creatures — many based on myths and fairy tales — like a monopod, two griffins, a necromancer, a wicked papess, an otter king, a woman with three breasts, three brothers with dog heads who become accidental cannibals, a leucrotta, a Magyr, a skin seller, living stars fallen to earth … and these are just some of those that I can describe in a few words (and I’m not giving them justice). The characters in The Orphan’s Tales remind me of the Cantina Scene in Star Wars. The darker characters, (e.g., the wizard and the necromancer), are particularly excellent. Valente’s imagination for bizarre characters and plots exceeds Lewis Carroll’s and she never lets up. Each story is brilliant and brilliantly told.

And the prose is truly beautiful:

He was very tall, and thin as a length of paper. His skin and cloaks were the color of the moon — not the romantic lover’s moon, but the true lunar geography I had heard whispered by Sun-and-Moon Nurians come to buy glass for their strange sky-spying tools: gray and pockmarked, full of secret craters, frigid peaks, and blasted expanses. His eyes had no color in them save for a pinpoint pupil like a spindle’s wound — the rest was pure, milky white. He passed three solid gold pieces over my mother’s palm, and she shuddered in revulsion at his touch when the money changed hands. She handed me over eagerly, examining the coins like a fat pig snuffling at its supper slop.

This gave me chills:

My mother had kept silent as a nun since the day my sister was taken from her. I was an infant when she vanished from us; I never knew that sister. But her absence stalked the house like a hungry dog. The hole where she had been took up space at our dinner table, it sagged and slumped in the musty air, it ate and drank and breathed down all of our necks… I grew up alone in that silent house with nothing but the stinking cows and my mute mother and the hole. Even my father didn’t want to spend his days there; he stayed in the fields directing hay-rolling and goat-breeding until it was dark enough to slip back inside the house without anyone bothering him. But still, the hole answered the bell when he rang, and he had to scurry to bed with his head down to avoid looking it in the eye.

There are many more of these gorgeous passages to enjoy. My only complaint about the writing itself is that there are dozens of characters in The Orphan’s Tales and they ALL talk like that. So, it’s not very realistic, but I suppose realism wasn’t exactly what Ms Valente, a poet, was going for.

One other small complaint I have is that because the stories of The Orphan’s Tales seem at first to be random and unrelated, it’s hard to feel deeply involved with many of the characters because they don’t stick around for long (except for the orphan and the sultan’s son who don’t do much but talk and listen). But, again, that’s the point, because we learn at the end of In the Cities of Coin and Spice that all of the strange stories and characters actually contribute to, and explain, the history of the orphan girl. Perhaps that’s a bit of a spoiler, but you’ll enjoy the stories more if you realize that it’s all going somewhere. And, besides, you’re a clever reader, and you’ll probably figure out that there’s got to be something going on here besides just a bunch of beautifully-written, highly imaginative, unconnected stories.

But, the main reason I’m telling you this is because I know you’ll get more out of your reading if you follow the advice I’m going to give you… Just trust me:

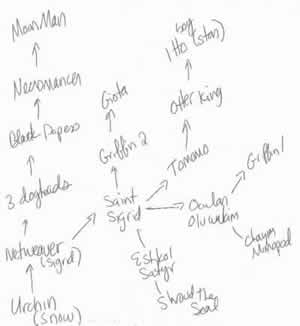

Get yourself a pencil, a pad of paper, and a fine cup of caffeinated coffee (in my experience, a Starbucks Venti Latte works best). Sit down with In the Night Garden and read the first few pages up to the point where the girl starts to tell “the first tale I was able to read, from the crease of my left eyelid.” This first story is about Prince Leander. Write “Prince Leander” at the bottom of your paper. Prince Leander runs into a gray-haired tattooed “crone” and a few pages later, she starts to tell her story. Write “crone,” or whatever you want to call her, above Prince Leander’s name. Soon, “crone” starts telling the story that her grandmother told her. Write “crone’s grandmother” above her name. I’m including here a picture of my notes for the second half of In the Night Garden. (Feel free to use them if you can read my handwriting.) As you see, things get complicated. This is not the kind of book you can leave for a few days and come back to unless you have notes to tell you who was talking to who. Or unless you’re a lot smarter than me, which is certainly possible.

Highly recommended for the reader who appreciates beautiful prose, is willing to take notes, and is looking for something original.

Fascinating. Intricate. Thanks for the tip on how to read these.