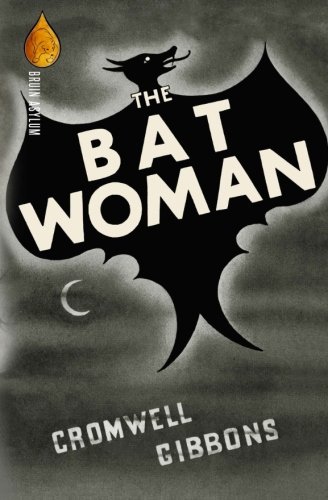

![]() The Bat Woman by Cromwell Gibbons

The Bat Woman by Cromwell Gibbons

As some of you may have discerned, my favorite type of reading matter these days has been the science fiction, fantasy and horror books from the period 1900 – 1950, and so I am always on the lookout for modern-day publishers issuing new editions of these often out-of-print works. Case in point: Bruin Books, from Eugene, Oregon, which, a few years back, made it possible for me to finally obtain a reasonably priced copy of Paul Bailey’s wonderful horror novel Deliver Me From Eva (1946). I was thus happy to read that Bruin has recently released a whole slew of horror works under its new Bruin Asylum label, and choosing at random, I selected the book in question, Cromwell Gibbons’ The Bat Woman (1938) … even though I had previously never heard of the author or this novel. But really, who could possibly resist this blurb on the back cover: “Prepare For Schlock And Awe … this wonderfully schlocky novel of evil menace was undoubtedly meant as a treatment for a Universal Studios horror picture. It has all the elements of a Saturday matinee fright fest: vampirism, mad scientists, head-hunters and yellow peril…”? Not me, that’s for sure!

Before I go on, a quick word on Cromwell Gibbons himself. Despite this Bruin edition’s claim that the author was a “Hollywood screenwriter,” a quick search on the IMDb discloses nobody with that name. Rather, Gibbons (1893 – 1977) is now believed to have been a chemical engineer, best remembered today (when he is remembered at all) for the two novels that he wrote featuring the ace criminologist Rex Huxford: Murder in Hollywood (1936) and the book in question, which was first released as a World Press hardcover and remained out of print for almost 80 years, till the fine folks at Bruin decided to resurrect it for a new generation. Today, that World Press edition sells for anywhere from $400 to $800, and I suppose I might have been forewarned when the online bookseller Biblio described its first-edition copy as “scarce (and deservedly so)”; a cryptic comment if ever there were one! As it turns out, The Bat Woman is a decidedly middling affair, but at least one with its heart in the right place. Sadly, this new Bruin offering makes a problematic novel even worse by dint of its stunningly sloppy presentation. More on this in a moment.

In Gibbons’ book, Huxford is called in to assist the wealthy “African big-game sportsman” Colonel Hadlow Winthrop, whose son Robert is currently on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Robert’s young bride, Cynthia, had died several months earlier, the victim of some sort of exotic sleeping sickness, but just a few days ago, the young man had seen her sitting in a balcony seat at the Metropolitan Opera in NYC, accompanied by the monstrous figure of Eric von Schalkenbach, a German scientist who resembles more than anything a gorilla (the result of some unfortunate inbreeding), and whom Cynthia had been somehow infatuated with before her marriage! The stunned widower had later seen Cynthia again, near Lincoln Center, and had sent his best friend, a husky All-American football player, in pursuit of her via taxi. But that friend had later turned up dead, laying in the snow in Washington Sq. Park, his body drained of blood. During his subsequent investigation, alongside dim-witted cop Inspector Hogan, Huxford visits the local morgue and learns that several others have recently turned up in a similarly exsanguinated condition, the telltale bite marks of a vampire bat on their necks. And when Robert later encounters a strangely changed Cynthia in the Trinity Church graveyard one snowy night (possibly the book’s finest scene), and notices her eyes glowing in the dark, and her aversion to light, and her ability to make the flower in his lapel wither just by her mere proximity, suspicions become certainty: Cynthia is now one of the living dead, has been revivified somehow by Schalkenbach, and is currently a ravenous predator seeking human blood…

Now, regarding this Gibbons novel, there is good news, bad news and worse news. Let’s start with the good. The Bat Woman really is as pulpy as they come (yes, that’s a compliment, coming from me!), and really would have made for a wonderful Universal horror film, although just who in the Universal stable might have portrayed the enormous Schalkenbach I really cannot say. The book seems to bust a gut to be sensational and shocking, mixing in as it does reefer smoking (“He must have been a Mary Warner dope,” Hogan says at one point of Robert), morphine use, a primer on Amazonian headshrinking, a midnight exhumation in a snowbound cemetery, that grisly visit to the morgue, cannibalism, murder by neck snapping, and experimentation on a living head (that last bit a full 25 years before the horror classic The Brain That Wouldn’t Die). Interpolated into the actual tale we have side stories related by some of the characters in passing, and these anecdotal bits are often of more interest than the main goings-on themselves. Thus, we hear of how one of the colonel’s friends, an explorer, had first encountered Schalkenbach in the depths of the Amazon jungle, where he was seen battling an enormous crocodile. The colonel’s missionary friend follows up with a tale in which the pastor had encountered Schalkenbach on a schooner traveling from the Celebes to Java, during a tremendous typhoon. (And by the way, any book that mentions the Celebes, an island of longtime curiosity for me, gets extra points from this reader; up until now, only James Blish’s 1973 novel The Quincunx of Time had made any reference to it.)

Now, regarding this Gibbons novel, there is good news, bad news and worse news. Let’s start with the good. The Bat Woman really is as pulpy as they come (yes, that’s a compliment, coming from me!), and really would have made for a wonderful Universal horror film, although just who in the Universal stable might have portrayed the enormous Schalkenbach I really cannot say. The book seems to bust a gut to be sensational and shocking, mixing in as it does reefer smoking (“He must have been a Mary Warner dope,” Hogan says at one point of Robert), morphine use, a primer on Amazonian headshrinking, a midnight exhumation in a snowbound cemetery, that grisly visit to the morgue, cannibalism, murder by neck snapping, and experimentation on a living head (that last bit a full 25 years before the horror classic The Brain That Wouldn’t Die). Interpolated into the actual tale we have side stories related by some of the characters in passing, and these anecdotal bits are often of more interest than the main goings-on themselves. Thus, we hear of how one of the colonel’s friends, an explorer, had first encountered Schalkenbach in the depths of the Amazon jungle, where he was seen battling an enormous crocodile. The colonel’s missionary friend follows up with a tale in which the pastor had encountered Schalkenbach on a schooner traveling from the Celebes to Java, during a tremendous typhoon. (And by the way, any book that mentions the Celebes, an island of longtime curiosity for me, gets extra points from this reader; up until now, only James Blish’s 1973 novel The Quincunx of Time had made any reference to it.)

And then there are the marvelous tales that Huxford himself spins, while sitting in the cozy den of the colonel’s Gothic mansion in Larchmont: the story of an Indian yogi being buried alive for 40 days and surviving, of a real-life vampire near the European town of Graditz, of a Russian vampire discussed in Madame Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled, of the Trinidadian vampire bats told of in Ditmars and Bridges’ Snake-Hunter’s Holiday, and of the experiments on man-made vampires conducted by the (fictitious) Russian scientist Serge Crususviski. It is all fascinating stuff, nicely depicted by Gibbons. His book is well paced and makes fine use of its many NYC locations. There are also some nifty touches to be had, such as Schalkenbach’s referring to Cynthia as Princess Desmodus (the Latin name for the vampire bat is “Desmodus rufus”), and the sight of the mad German sitting in his secret Washington Sq. hideout, playing Wagner’s “Die Meistersinger” on his organ (a nod to Boris Karloff playing that old horror staple, Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor,” on his organ in the 1934 classic The Black Cat, perhaps).

Anyway, that’s the good news. The bad news is that Gibbons’ book is an often confused and confusing affair, and I must admit that Schalkenbach’s central project was one that I just couldn’t fully understand. As far as I can make out, he used vampire bats to bring Cynthia to the brink of death, but I am unclear as to whether or not the poor gal ever really expired or not. Later, the mad German used the blood of vampire bats that had recently feasted on human victims to bring her back, inadvertently turning Cynthia into a vampire herself, and thus necessitating further scientific tinkering to make her human again. Or something like that. Also, why does this grand experiment fail so dismally in the final scene? Don’t ask me. Further points must be deducted for a terribly rushed ending (admittedly, a feature of many of those Universal horror pictures), offhand racism (frequent use of the “n word,” continual references to Schalkenbach’s Chinese servant as a “Chink,” and a Stepin Fetchit-like waiter named Zipp in Col. Winthrop’s Explorers Club) that is an unfortunate commonplace for the era, and the fact that there is very little character development to speak of. Indeed, even Huxford, our supposed main character here, remains something of a cipher to the reader by the book’s end; all we learn about him is that he is slender, around 40, and is never seen without a Malacca cane. (Perhaps Gibbons gave us all we need to know in that first Huxford novel? Dunno.) So as you can tell, The Bat Woman must go down as something of a mixed bag, fun enough though it undoubtedly is.

But wait … as I said, there’s worse news, still, and that is the deplorable presentation of this Bruin Asylum offering itself. Simply put, the book is a mess, with hundreds of instances of typos and faulty punctuation … surprising, given that the Bailey novel had been so pristine. Here, though, “snapped” becomes “mapped”; “floor” becomes “Boor”; “flung” becomes “Hung”; “tone” becomes “toile.” Instead of “through,” we get “throng”: instead of “flames,” “Hames”; instead of “flow,” “How.” And on and on and on. Even worse, though, is the arbitrary use of quotation marks, often making it difficult to tell whether one of the characters is speaking or not, and the repeated use of superfluous commas (“He shook, his head slowly, hopelessly.” “They, stepped into a well-kept enclosure.”). It becomes painfully obvious, as one reads — or, rather, deciphers — this Bruin edition, that the book has never been proofread. When will publishers realize that Spell Checking is never good enough? This is the second modern volume in a row that I’ve read that has boasted inexcusably bad typography (the first was Armchair Fiction’s Allison V. Harding: The Forgotten Queen of Horror), and I am beginning to wonder what has happened to publishers’ pride in beautifully put-together books. Gibbons’ novel, middling as it is, deserves so much better. Bruin Asylum has in its collection at least three other novels that I’d love to purchase one day — Gordon Casserly’s Tiger Girl (1934), G. S. Marlowe’s I Am Your Brother (1935) and C. S. Cody’s The Witching Night (1953) — but after being rooked by this disgraceful presentation (for which I am docking this volume one complete star), I am more than a little leery. As Cynthia Winthrop might have said herself, “Once bitten, twice shy”…

There are typographical glitches that happen when text is scanned with some scanning software. When I see those random commas or quotation marks like this:

” No!””” she said.

…I often assume that’s the source. Still no excuse for a lack of proofreading.

…especially when the book is a new release that has been out of print for decades. You’d think the publisher would be proud to be the one to bring back this lost book, and would take extra efforts to make the release something special. But no….

This kind of nonsense is, sadly, still typical of OCR (Optical Character Recognition) 30 years after it was first used. In my experience, it’s common for publishers to run OCR and then not even spellcheck, let alone proofread, and especially if the original edition was cheaply printed (and so doesn’t have very clear type to begin with), this always produces an awful result.

It is sad indeed, Mike. And as a copy editor and proofreader myself, I find the practice especially offensive….

This seems like a short-sighted business decision. People who are paying for hardcopy edition of long out-of-print book probably love books as an artifact, and readability is one of their factors. These companies will not maintain customers if they don’t try to improve.

Case in point: me, who would have automatically purchased those three other books that I mentioned in the last paragraph of this review, and who am now leery about doing so….