SHORTS: Our column exploring free and inexpensive short fiction available on the internet. This week’s post reviews several more of the current crop of Locus Award nominees in the short fiction categories.

![]() “A Brief Lesson in Native American Astronomy” by Rebecca Roanhorse (2019, anthologized in The Mythic Dream, edited by Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

“A Brief Lesson in Native American Astronomy” by Rebecca Roanhorse (2019, anthologized in The Mythic Dream, edited by Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

In the future, people’s memories can be stored and preserved even after they’ve died, and other people can inject them like drugs. Dez Hunter is an actor who has spiraled into depression after the death of his beloved girlfriend, Cherie. His boss brings him a vial of Cherie’s memories in the hopes that it’ll help him get over it and fulfill his contractual obligations.

What happens instead is that Cherie returns to him, in the flesh. At first, Dez is delighted, luxuriating in their reunion. But the honeymoon soon begins to spiral into horror.

“A Brief Lesson in Native American Astronomy” is a story about love and grief that gleams with cutting-edge technology but also feels timeless. Along the way, it also has some pointed things to say about celebrity culture and Native American stereotyping in Hollywood. It’s sad, beautiful, and brilliant, and is a finalist for the Locus Award for Best Short Story.

Rebecca Roanhorse based her tale on the Tewa legend of Deer Hunter and White Corn Maiden. I was unfamiliar with this story, but looked it up and read it after reading “A Brief Lesson in Native American Astronomy,” and appreciated Roanhorse’s rendition even better in retrospect, as it incorporates all of the major plot elements of the myth while translating them into a futuristic setting. I would recommend reading “A Brief Lesson in Native American Astronomy” first, as the myth will spoil some things for you, but do read both to get the full effect of the adaptation. ~Kelly Lasiter

![]() “Thoughts and Prayers“ by Ken Liu (2019, free at Slate magazine, part of the Future Tense series). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

“Thoughts and Prayers“ by Ken Liu (2019, free at Slate magazine, part of the Future Tense series). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

A college student, Hayley Fort, is randomly killed in a mass shooting at a California music festival. Her distraught parents and younger sister Emily react differently to the tragedy, but when her mother Abigail takes up an offer to use cutting-edge technology to “craft a visual narrative of Hayley’s life” that, they hope, will spur viewers to take action on gun control, it triggers all kinds of unintended consequences, in a progressively more alarming series of events, beginning with online trolling, each compounding the tragedy.

Ken Liu tells this story in a documentary style, as a series of interviews by the key players: Hayley’s sister Emily, who realizes that the video recreation of Hayley’s life only tells part of the story; her father Gregg, who wants to rely on his internal memories of Hayley rather than digital ones; her mother Abigail, who charges forward with others’ plans to memorialize Hayley, to her ultimate grief; Gregg’s sister Sara, who tries to help the Fort family with state-of-the-art defensive neural networks, called “armor,” that shield the users from unwanted digital and visual content that causes the users emotional pain. Even a troll gets their say, railing against the sanctimonious and defending their “RIP-trolling,” ultimately encompassing all of our guilty actions in one way or another.

It’s a fascinating, disturbing story told by Liu with consummate skill, who shows us the many facets of the problem and avoids over-simplifying a complicated issue. ~Tadiana Jones

![]() “I (28M) created a deepfake girlfriend and now my parents think we’re getting married“, Fonda Lee (2019, free at MIT Technology Review 12/27/19) (subscription website with limited free article views). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

“I (28M) created a deepfake girlfriend and now my parents think we’re getting married“, Fonda Lee (2019, free at MIT Technology Review 12/27/19) (subscription website with limited free article views). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

This near future science fiction story plays on the kind of posts and questions you might find in relationship based subreddits, or maybe even some of the question-and-answer based sites. The title and format are in reference to the whole genre of juicy relationship troubles and advice that the internet loves to watch go down.

Lee nails the tone of this weird corner of the internet, to the strength of the story. The choices the character makes are understandable — he’s just a guy who wants his parents off his back about getting a girlfriend — but he makes terrible decisions about this perceived problem, leading to his post asking the internet for help.

I call this piece ‘near future science fiction’ because the format is such a product of right now, but the technology within is — to my understanding — beyond current reality. On my second reading of the story, the ending stood out: it’s the right kind of ambiguous that could be implying any number of futures for the main character. It doesn’t surprise me that the story is up for the Locus Award in the Short Story category. ~Skye Walker

(Editor’s note: Tadiana Jones also reviewed this story in our June 6, 2020 SHORTS column and rated it 3.5 stars.)

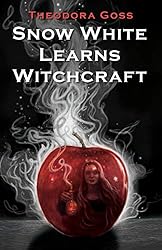

![]() A Country Called Winter by Theodora Goss (2019, free at Lightspeed magazine, $1.99 in author’s collection Snow White Learns Witchcraft). 2020 Locus Award finalist (novelette).

A Country Called Winter by Theodora Goss (2019, free at Lightspeed magazine, $1.99 in author’s collection Snow White Learns Witchcraft). 2020 Locus Award finalist (novelette).

Vera is a graduate student in Boston with only dim memories of her childhood in a remote European principality whose name can be translated as “Winter.” She has a love affair with an undergraduate that ends badly, but just when he comes back contrite, she also learns more about her importance to Winter and has a choice to make.

A Country Called Winter is a fairy tale retelling, and I’ll let you discover the tale for yourself as you read. Theodora Goss humanizes a character who was not sympathetic in the original (while making the other major female character from the tale pretty awful), and develops her realm into a place that could exist in reality — though there is magic here, of a subtle sort. Goss’s writing is elegant, especially lovely when describing the beauties of winter and Vera’s love of literature.

It’s not particularly groundbreaking or mind-blowing, but it’s simply a pleasure to read, and makes for a nice break from the summer heat or from grittier works that you might be reading. There’s a scene in it where Vera sips cappuccino in a cozy coffee shop on a cold day, and that’s exactly what A Country Called Winter feels like. ~Kelly Lasiter

![]() “Fisher-Bird” by T. Kingfisher (2019, anthologized in The Mythic Dream, edited by Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

“Fisher-Bird” by T. Kingfisher (2019, anthologized in The Mythic Dream, edited by Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

One of the best things about T. Kingfisher’s “Fisher-Bird,” a finalist for the Locus Award for Best Short Story, is the delightful narrative voice — which won’t surprise anyone who’s read her novel The Twisted Ones. Here it’s folksy and sarcastic, often hilarious. It’s like listening to a story told by your grandmother, if your grandmother had a bit of a potty mouth and didn’t suffer fools. I bet this would be great in audio.

“Fisher-Bird” tells a folk tale of how the titular bird got its belt of red plumage. This comes about when Fisher-Bird’s path intersects with that of Hercules (here called Stronger) in the middle of his twelve labors. But since this version is set in the American South, the beasts that Stronger battles are adapted correspondingly; for example, he has killed a mountain lion rather than a regular lion.

Stronger’s next task is to clear out the stimps (Stymphalian birds). Fisher-Bird hates them too and hatches a plan to help him. At one point I thought I’d figured out a twist about what the stimps really are — and I thought this was an incredible reveal — but the way things happened in the climactic scene, I’m not actually sure I was right. So I’m a little confused. But I’m still happy to have spent a little time with Kingfisher’s narrative voice and creative interpretation of the myth. ~Kelly Lasiter

![]() A Time to Reap by Elizabeth Bear (2019, free at Uncanny magazine; $3.99 Kindle magazine issue). 2020 Locus award finalist (novella).

A Time to Reap by Elizabeth Bear (2019, free at Uncanny magazine; $3.99 Kindle magazine issue). 2020 Locus award finalist (novella).

In this time-travel novella, Kitty Whelan, a petite 16-year-old actress in the year 2028, is playing the part of 12-year-old Sissy in the play Time to Reap, based on a real-life series of unsolved murders that took place in 1978 at the Abbott family reunion. The cast, along with a few reporters, takes an excursion to the Massachusetts farm where the reunion and murders occurred fifty years earlier. When Kitty sneaks off to the barn, she’s yanked back in time to 1978, before the murders have occurred. She meets Margaret Abbott, inadvertent inventor of a time machine … who Kitty knows will be the first victim of the murderer.

Kitty quickly convinces Margaret that she’s from the future (she doesn’t mention the pending murders) and Margaret introduces Kitty to the clan as her great-niece. As Kitty meets Sissy, who will also be one of the murder victims, and gets to know various members of the Abbott clan, she dithers about time paradoxes, changing the past and whether to say anything to the people she’s befriending. She also becomes aware of some of the undercurrents and tensions among the Abbotts … and she may herself be in danger from the murderer.

Kitty has her own issues to deal with, mostly arising out of her stage mother’s controlling behavior and diet demands on Kitty, that add some nuance to this story. It’s fun to see the past through Kitty’s eyes, especially where the play she’s been rehearsing diverges from reality, and her surprise at some of the things (like children traveling alone) that people took for granted in the 1970s.

Meeting one Abbott after another … I realized what made them such a weird-looking family. What had been bothering me on the way up the stairs.

Every last one of them was white. The whole family.

The past really is a different country.

The story loses some steam toward the end as the plot — and the treatment of time travel and multiple timelines — get a little muddled. The ending raises some interesting ideas, though, and I overall I enjoyed A Time to Reap. ~Tadiana Jones

![]() Erase, Erase, Erase by Elizabeth Bear (Sep/Oct 2019 issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction magazine). 2020 Locus award finalist (novellette).

Erase, Erase, Erase by Elizabeth Bear (Sep/Oct 2019 issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction magazine). 2020 Locus award finalist (novellette).

The first person protagonist of Elizabeth Bear’s Locus-nominated novelette, Erase, Erase, Erase, finds herself losing bits and pieces of herself — a hand left under the bed, an ear stuck on a discarded earbud. Sometimes her hand won’t solidify sufficiently for her to drink her cup of coffee. Pens and notebooks have stayed solid so far, and the parts that fall off stick right back on, but she keeps feeling that she’s forgotten something very important.

This woman has been trying to erase herself from the world for most of her life. Every time she made a mistake, she walked away, moved on, tried to forget, burned the notebooks in which she’d written about it. An abusive family background, jobs that didn’t turn out well, bad bosses, failed love affairs: all gone. She never learns anything from the mistakes, because how could she when she’s forgotten about it?

Bear’s character is an unhappy person who has never tried to be happy. As the story begins, she has only started to understand that she has made mistakes that can’t be forgotten, that must be remembered, not just for herself, but for the rest of the world. She wrestles with her lovely fountain pens and the pages left at the end of notebooks she’s put away, trying to write to remember what she must before she can longer handle the pen — it’s hard enough to write without being able to rest her hand on a desk. She continues to lose more of herself, to the point that she can no longer eat or drink; she can’t solidify long enough to fill a glass of water and raise it to her lips.

The metaphor of disappearing works well in this story, and the images of a woman becoming a ghost are vivid. But the story is slow and repetitive, and the payoff at the end is wholly expected. The story lacks tension. It’s Bear’s work, which means it is plenty readable, with lovely use of language and rhythm, but it’s not one of her best. ~Terry Weyna

![]() “Lest We Forget“ by Elizabeth Bear (2019, free at Uncanny magazine; $3.99 Kindle magazine issue). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

“Lest We Forget“ by Elizabeth Bear (2019, free at Uncanny magazine; $3.99 Kindle magazine issue). 2020 Locus award finalist (short story).

In this third of Elizabeth Bear’s short fiction Locus nominees, Lee is a former soldier traumatized by his war memories, especially those involving the deaths of innocent people and the torture and atrocities in which he participated. He was “just following orders,” but he admits that that doesn’t absolve his guilt. When he sees an advertisement offering free help to military personnel suffering from PTSD, he answers it. But the “help” is of a much different kind than he expected: Dr. Cotter, a neuroscientist, is looking for an ex-soldier to volunteer to allow genetically edited flatworms to absorb the memories from his brain and turn the flatworms loose on everyone else on Earth, to imprint Lee’s horrendous wartime memories on other people and, hopefully, bring about an end to war.

“Lest We Forget” combines anti-war sentiment with an extrapolation of scientific experiments showing that flatworms can display the learned memories of other flatworms that they have eaten. It’s well-written and has an intriguing twist to it that’s alluded to early in the story, but isn’t expressly stated until the end.

At the same time, it’s a deeply disturbing plot that violates the personal rights of every person on earth, the innocent as well as the guilty. Cotter and Lee admit that what they’re doing is terrible (“That sounds like terrorism. Not to mention one hell of a violation of consent law.”) but they decide that the end — seeking an end to war — justifies the means. But it’s not at all certain that their hoped-for outcome will be achieved, and their action seems far more likely to result in tremendous problems and crippling breakdowns in society and people. And … why wouldn’t this also affect our planet’s animals? ~Tadiana Jones

I’m noticing a theme through several of these stories–looks like we’ve got memories on our minds!

Kelly, I bought a copy of The Mythic Dream because of all your reviews of the award-nominated stories in it. :) I’ve read a few of them, and now I’m really curious about your theory of the Stymphalian birds in the T. Kingfisher story. Mind sharing it?

I thought they were oil drilling equipment! And that the fisher-bird, not really having the context to know that, interpreted them as birds. And since we dig oil out of the earth, it makes sense that they’d come “from Hades,” so to speak. (For more on that, see my upcoming review of Desdemona and the Deep!)

But if that was the case, then poison wouldn’t have done anything to them, plus they talked to her like any other animal and made a snarky comment about humans to her.

I agree that’s not the direction the story went, but that would’ve been a really fascinating twist!

Also, if you liked the folksy narrative voice in “The Fisher-Bird” (lol at “grandmother with a potty mouth” and you haven’t yet read this author’s award-winning stories “Jackalope Wives” and “The Tomato Thief,” you absolutely have to read them. Grandma Harken is the marvelous main character and narrates both stories. Reviews and links to these two stories (both online freebies) are here:

https://fantasyliterature.com/reviews/sfm-ursula-vernon-robin-sloan-k-j-parker-edgar-allen-poe-ray-wood/

https://fantasyliterature.com/reviews/sfm-leigh-brackett-nghi-vo-ursula-vernon-kate-bachus-joe-abercrombie/