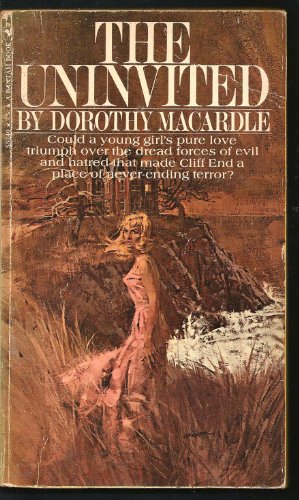

![]() The Uninvited by Dorothy Macardle

The Uninvited by Dorothy Macardle

Although 1944’s The Uninvited has long been one of this viewer’s favorite spooky movies of that great filmmaking decade, it wasn’t until fairly recently that I learned of the special place it holds in cinema history. The film, apparently, was the very first Hollywood product to treat ghosts seriously. Here, at last, the specters on display were not hoaxes, not fakes, and not played for laughs. Rather, they were completely legit; supernatural survivors with unfinished business here on the material plane. Featuring first-rate acting by a cast of pros, impressive direction by Lewis Allen in his first feature-length film, a theme song that would go on to become a classic, remarkable (for its time) special FX, and stunning, noirish and Oscar-nominated cinematography by the great Charles Lang, the picture is a very solid entertainment, indeed, if perhaps a tad tame for today’s horror buffs … especially those who require gallons of the red stuff to experience a shiver. Anyway, I had long wanted to check out the currently out-of-print source novel for The Uninvited, and after some Interwebs searching, was easily able to lay my hands on a copy (a 1969 Bantam paperback). This novel, written by Irish author Dorothy Macardle (1889 – 1958), was initially released in the U.K. in 1941 under the title Uneasy Freehold; one year later, it appeared in the U.S. with its more well-known appellation, The Uninvited. Remarkably, this was Macardle’s first novel, after having come out with several books of Irish history previous to this, including her highly esteemed volume The Irish Republic (1937). As it turns out, Macardle’s novel is easily more nerve wracking than the film it begat several years later; a wonderful exercise in slow-burn suspense. This reader was recently made happy to discover that his other favorite ghost movie of the ‘40s, 1947’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, had as its source novel something even richer and deeper (check out R.A. Dick’s 1945 novel of the same name for proof), and such is the case here, as well.

In Macardle’s book, the reader is introduced to Roderick and Pamela Fitzgerald. Roderick is a 29-year-old book and theater critic, as well as an aspiring playwright; his sister, Pamela, is 23, and at loose ends after having nursed their dying father for six years. While motoring through the northern part of Devonshire, the two fall in love with an abandoned abode, Cliff End, which sits high atop the Bristol Channel. To their great delight, they are able to purchase the place on agreeable terms from the owner, 18-year-old Stella Meredith, whose mother Mary had died tragically after falling off the nearby precipice 15 years earlier, and whose father, a painter, had died at sea three years after that. Stella currently lives with her grandfather, an ex-naval officer named Commander Brooke, who seems decidedly uncomfortable with the sale. But despite that, Roderick and Pamela do indeed move in a few months later, and all seems to go well at first. But before long, the moaning cries of a female are heard at night; Judith, the wife of one of Roderick’s best friends, is horrified to see her face in the mirror appear as a leering death’s head; their maid, Lizzie, is terrified by the ghostly image of a woman at the upstairs bannister; an overpowering aroma of mimosa and a paralyzing chill are encountered, respectively, in the downstairs nursery and the upstairs studio; the visiting Stella — entering the house for the first time in 15 years — becomes crazed with the belief that her deceased mother is trying to contact her; and the Fitzgeralds’ cat and Scottish terrier are reduced to cowering fear. And after a séance is held, the dire truth becomes known, and it is even worse than imagined: Not only is the ghost of Mary Meredith haunting Cliff End for reasons of her own, but there appears to be another ghost present, as well; the ghost of Carmel, a Spanish gypsy who had once served as Mary’s husband’s model … a woman who, when alive, was reputed to be a very bad sort…

The Uninvited starts off slowly, its first 50 or so pages mainly detailing the Fitzgeralds’ moving in and getting to know their neighbors and village, the fictional Biddlecombe. Things do pick up in a big way with those initial “occurrences,” however, and it must be said that every single manifestation is a frightening one. The characters here react quite convincingly and realistically when faced with the supernatural: Roderick becomes paralyzed and unable to speak; Pamela becomes sick to her stomach; Judith is driven to “weeping helplessly.” Macardle holds the reader’s interest by having Ingram, a young but passionate “ghost buster” friend of theirs, provide various explanations for the phenomena, as well as give us a scientific discourse on the nature of ectoplasm, and why ghosts engender a feeling of cold. Ultimately, of course, the real explanation for the hauntings is revealed, and it is one that few readers will foresee; a truly fascinating and involved backstory. Macardle’s novel builds to a tense, atmospheric, and, indeed, claustrophobic final quarter, only to wind up with a wonderfully touching conclusion. Along the way, the author throws in several well-done and suspenseful scenes — I particularly enjoyed the two séances, including Pamela’s possession during the latter — and fleshes out her book with any number of interesting secondary characters. Thus, we are given Judith and Max, the latter being an artist friend of Roderick’s; Wendy and Peter, a pair of newlyweds who are also good friends of Roderick’s, as well as being very eccentric actors; Dr. Scott, the youngish village physician who seems to be harboring a crush on Pamela; and Father Anson, the local priest who urges the Fitzgeralds to employ the drastic recourse of exorcism, much to Stella’s horror.

Macardle’s novel, to its credit, is nicely detailed — some might say overly detailed — and yet, somehow, this reader could never quite get a proper mental image of the layout of Cliff End’s interior, or of the village or surrounding countryside. Curiously, though written in 1941, not a single mention of WW2 from narrator Roderick is to be found; only a passing reference to “the war in Spain,” near the book’s end, lets us know that the story takes place between 1936 and 1939. Naturally, this is a very British sort of experience, and readers must thus be prepared for a good deal of English slang words before venturing in (or perhaps you already know what a “dew-bit” is?). Another thing that readers should anticipate is the large number of literary and cultural references that Roderick (who, as a book critic, would be expected to be well-read), his sister and friends are apt to toss back and forth. A little research on my part revealed that the quotes and references hail from such disparate sources as Shakespeare, A.A. Milne, G.K. Chesterton, Lewis Carroll, William Wordsworth, Irish politician Boyle Roche, sculptor Jacob Epstein and playwright William Archer … all giving some literary cachet to the proceedings, I suppose. Although Roderick, toward his narrative’s end, describes his story as both “sheer melodrama” and “far-fetched,” it is more likely that most readers will rather agree with Ingram when he declares “it is the most enthralling thing of the sort that I have ever encountered. You know, you have a psychic-researcher’s paradise here!” Finely written and often fairly scary, The Uninvited is surely quality fare for modern-day horror readers.

Macardle’s novel, to its credit, is nicely detailed — some might say overly detailed — and yet, somehow, this reader could never quite get a proper mental image of the layout of Cliff End’s interior, or of the village or surrounding countryside. Curiously, though written in 1941, not a single mention of WW2 from narrator Roderick is to be found; only a passing reference to “the war in Spain,” near the book’s end, lets us know that the story takes place between 1936 and 1939. Naturally, this is a very British sort of experience, and readers must thus be prepared for a good deal of English slang words before venturing in (or perhaps you already know what a “dew-bit” is?). Another thing that readers should anticipate is the large number of literary and cultural references that Roderick (who, as a book critic, would be expected to be well-read), his sister and friends are apt to toss back and forth. A little research on my part revealed that the quotes and references hail from such disparate sources as Shakespeare, A.A. Milne, G.K. Chesterton, Lewis Carroll, William Wordsworth, Irish politician Boyle Roche, sculptor Jacob Epstein and playwright William Archer … all giving some literary cachet to the proceedings, I suppose. Although Roderick, toward his narrative’s end, describes his story as both “sheer melodrama” and “far-fetched,” it is more likely that most readers will rather agree with Ingram when he declares “it is the most enthralling thing of the sort that I have ever encountered. You know, you have a psychic-researcher’s paradise here!” Finely written and often fairly scary, The Uninvited is surely quality fare for modern-day horror readers.

But getting back to the film, it is essentially a solid and faithful adaptation, with some important differences. Thus, in the cinematic version, many of those secondary characters — such as Father Anson, Max and Judith, Peter and Wendy — are completely eliminated, as well as the scenes that they appear in (such as the book’s extended housewarming sequence). Roderick is a music critic and aspiring composer in the film, rather than a drama critic and wannabe playwright, which allows the character to perform, on piano, the haunting “Stella By Starlight” melody (actually written by Victor Young) that would later become an American standard. The name of the creepy abode has been changed from Cliff End to Windward House, while Commander Brooke’s name, for some wholly inexplicable reason, has been changed to Commander Beech. Several scenes have been invented whole cloth for the film, such as the one in which Roderick and Stella go sailing, and the one in which we see flowers wilting in the house’s ghostly aura. The character of Miss Holloway, who was Mary’s best friend and Stella’s onetime nurse, has been significantly beefed up for the film, to the point that she becomes an evil plotter on the order of Mrs. Danvers in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940); in the Macardle novel, her presence is confined to a single chapter, in which she gives the Fitzgeralds some background information. The film also makes Stella the victim of that ghostly possession, instead of Pamela, and has the Commander meet his end at Windward House, instead of in a hospital.

But despite all these changes, the film still works marvelously. Ray Milland (here one year away from his Oscar-winning role in 1945’s The Lost Weekend), Ruth Hussey (four years after being Oscar-nominated for her work in The Philadelphia Story) and Gail Russell (who many will recall as the Quaker girl from the 1947 John Wayne classic Angel and the Badman) all turn in terrific performances as Roderick, Pamela and Stella, and the great character actors Donald Crisp (Commander Beech), Alan Napier (Dr. Scott) and Cornelia Otis Skinner (Miss Holloway) are also very fine, if hardly as described in Macardle’s book. Lewis Allen’s direction is taut, utilizing close-up shots very effectively, and Charles Lang’s B&W photography is a thing of genuine beauty; Lang would later bring his considerable talents to such film classics as The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, The Big Heat and Some Like it Hot. And oh my goodness, aren’t those ectoplasmic special FX by Gordon Jennings (who would go on to create more magic in 1953’s The War of the Worlds) truly something special? You’ll marvel at how these spectral manifestations swirl and throb, almost but not quite suggesting a malevolent female form. And as for the film’s shooting script, which was adapted by Frank Partos and Dodie Smith, because it eliminates quite a bit from the source novel, it makes for a concise and streamlined experience, with zero flab and very little in the way of extraneous detail. The novel and the film, thus, are different but complementary experiences, and both are highly recommended. I’d give the book a ½ star more than the film, however; for me, that’s where the true chills reside…

I always loved this movie. The book sounds enjoyable.

As I said, Marion, if you enjoyed the movie, you’ll likely find the book even deeper, richer and–most importantly–more chilling….