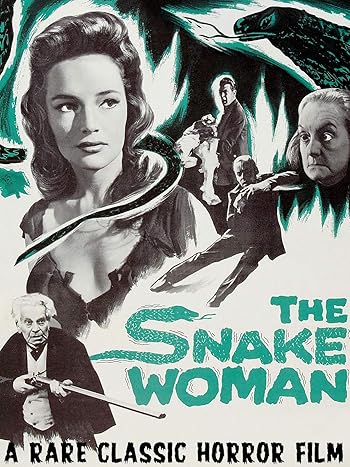

![]() The Snake Woman directed by Sidney J. Furie

The Snake Woman directed by Sidney J. Furie

In John Gilling’s 1966 film The Reptile, produced by Hammer Studios, the audience was presented with the spectacle of a young woman (the great Jacqueline Pearce) who, thanks to the ministrations of a Malaysian snake cult, could turn into a serpent at will. The film was set in the Cornwall area in the early 20th century and had been brought in at a budget of over 100,000 pounds … and with terrific and scarifying results. But, as it turns out, this was not the first time that the Brits had given us a story about a young woman who could turn herself into a snake, and who terrorized her vicinity in the early 1900s. Five years earlier, an infinitely smaller and lesser film, nearly forgotten today, had appeared, by name of The Snake Woman, and a recent watch has only served to impress upon this viewer what an inferior product it is, in comparison. Whereas The Reptile had featured sumptuous color and sets, as well as a very memorable and hideous-looking monster, The Snake Woman, which was filmed in just six days at a cost of some 17,000 pounds, and in B&W, features none of those attributes. Still, it is a film worth seeing, if one only lowers his or her expectations going in.

In John Gilling’s 1966 film The Reptile, produced by Hammer Studios, the audience was presented with the spectacle of a young woman (the great Jacqueline Pearce) who, thanks to the ministrations of a Malaysian snake cult, could turn into a serpent at will. The film was set in the Cornwall area in the early 20th century and had been brought in at a budget of over 100,000 pounds … and with terrific and scarifying results. But, as it turns out, this was not the first time that the Brits had given us a story about a young woman who could turn herself into a snake, and who terrorized her vicinity in the early 1900s. Five years earlier, an infinitely smaller and lesser film, nearly forgotten today, had appeared, by name of The Snake Woman, and a recent watch has only served to impress upon this viewer what an inferior product it is, in comparison. Whereas The Reptile had featured sumptuous color and sets, as well as a very memorable and hideous-looking monster, The Snake Woman, which was filmed in just six days at a cost of some 17,000 pounds, and in B&W, features none of those attributes. Still, it is a film worth seeing, if one only lowers his or her expectations going in.

The Snake Woman debuted in April ’61 in the U.S. as part of a double feature, the other film on the menu being the superior picture Doctor Blood’s Coffin; both films shared the same director, Sidney J. Furie. Strangely enough, The Snake Woman would have its premiere in the U.K. after it first appeared in the U.S., playing variously as the co-feature with such films as (the baby-boomer favorite) The Manster (’59) and The Vikings (’58). Running just 68 minutes in length, the film at least has the virtue of being a streamlined affair, wasting little time in telling its story. In it, the viewer is introduced to a herpetologist — an expert in reptiles and amphibians — named Dr. Horace Adderson (English actor John Cazabon, whose filmography extends mainly to TV work) … and I suppose with a name like “Adderson,” it was inevitable that this scientist would specialize in the study of snakes!

Adderson lives in the small Northumberland village of Bellingham in the year 1890, and keeps busy by devising serums made of various snake venoms to administer to his wife Martha (Dorothy Frere, who would go on to appear in the fun horror film It! in ’67), as a means of curing her mental illness. But the pregnant Martha turns out to be wiser than her husband, when she declares, “Life is such a miraculous, delicate thing. What if this poison were to upset the balance, and instead of a normal, healthy child, ours were to be born…” Her sentence is left unfinished, but soon after, that child, a daughter, is born, and she turns out to be a strange one indeed, with no lids over her eyes and with cold blood in her veins. The midwife on the case, Aggie Harker (Elsie Wagstaff, whose filmography dates all the way back to 1937), who is deemed something of a witch, wants to kill the child out of hand, but the presiding physician, Dr. Murton (German actor Arnold Marle, whose filmography goes back to 1919!), declares that she must be kept alive for study. Problems arise, however, when Aggie runs to the local tavern to warn the populace of the evil that has descended upon them, and when the torch-bearing townsmen break into Adderson’s lab to destroy it and kill the baby. Adderson is bitten by a snake and dies in the resulting conflagration, while Martha had already expired soon after childbirth. Thus, the baby is brought by Murton to the hut of a local shepherd for safekeeping, after which Murton himself departs for a trip to Africa.

After this intriguing setup, the film — with no sense of time transition whatsoever, not even an intertitle reading “Nineteen Years Later” — flashes forward 19 years. Murton, returning from his studies in Africa, learns that the child, now a grown woman, has disappeared. He also hears of the killings that have been plaguing Bellingham; of the villagers who have been slain with the bite of a king cobra on them, in an area of the world where no such creature should exist. And in the film’s second half, retired Army colonel Clyde Wynborn (Geoffrey Denton, who would go on to appear mainly in TV), a resident in the area, writes to a friend in Scotland Yard with a request for help. Thus, handsome Charles Prentice (John McCarthy, who would go on to appear in small roles in two of the great films of 1964, Goldfinger and Dr. Strangelove) is sent to the village, with orders to find out what is going on. Wynborn gives him a snake charmer’s flute, and while tootling it on the moors one day, Prentice runs into the Adderson girl herself, whom the shepherd had named Atheris, a name he’d found in one of Adderson’s books. (“Atheris,” by the way, is the name of a genus of pit viper.) The young woman is indeed 19 now, and, as played by British actress Susan Travers (whose other “psychotronic films” include 1960’s Peeping Tom and 1971’s The Abominable Dr. Phibes), is quite the looker indeed. Atheris is strangely drawn by the sound of the flute, and when Prentice puts his arm around her, is found to be ice cold to the touch. Hmm, what’s a bright young investigator from Scotland Yard to think?

After this intriguing setup, the film — with no sense of time transition whatsoever, not even an intertitle reading “Nineteen Years Later” — flashes forward 19 years. Murton, returning from his studies in Africa, learns that the child, now a grown woman, has disappeared. He also hears of the killings that have been plaguing Bellingham; of the villagers who have been slain with the bite of a king cobra on them, in an area of the world where no such creature should exist. And in the film’s second half, retired Army colonel Clyde Wynborn (Geoffrey Denton, who would go on to appear mainly in TV), a resident in the area, writes to a friend in Scotland Yard with a request for help. Thus, handsome Charles Prentice (John McCarthy, who would go on to appear in small roles in two of the great films of 1964, Goldfinger and Dr. Strangelove) is sent to the village, with orders to find out what is going on. Wynborn gives him a snake charmer’s flute, and while tootling it on the moors one day, Prentice runs into the Adderson girl herself, whom the shepherd had named Atheris, a name he’d found in one of Adderson’s books. (“Atheris,” by the way, is the name of a genus of pit viper.) The young woman is indeed 19 now, and, as played by British actress Susan Travers (whose other “psychotronic films” include 1960’s Peeping Tom and 1971’s The Abominable Dr. Phibes), is quite the looker indeed. Atheris is strangely drawn by the sound of the flute, and when Prentice puts his arm around her, is found to be ice cold to the touch. Hmm, what’s a bright young investigator from Scotland Yard to think?

The promotional poster for The Snake Woman declared the film to be “Weird! Supernatural! Horrifying!,” but of that list, only the first word turns out to be true. The film surely is weird, in the best sense, but it is hardly a supernatural affair (Atheris’ ability to change into a serpent and back to human form at will is the result of hard science, after all), and it is hardly ever horrifying. Indeed, in a film that purports to be a horror movie, there are only two scenes that might engender a chill in anyone who is not a hard-core sufferer of ophidiophobia. The first of those scenes involves Adderson forcing the venom out of the fangs of a king cobra, and it is a nerve-racking sight to behold indeed, an actual snake being used for the purpose. And in the second, we see a serpent of some kind crawling through the mouth of a human skull in Adderson’s burning lab. That’s it for the scares in the film. As for the rest of it, there is not a shudder to be had. The film never shows us one transformation scene, in which Atheris turns into her serpent form. We merely see the girl, then her potential victim, and then a snake crawling on the ground. Hey, I DID say the film was brought in for under 17,000 pounds, right? The victims of the Snake Woman never scream, or evince any high degree of fright either, so how can we viewers be expected to have much in the way of scares ourselves? So yes, this is a horror film with virtually no horrors to be had or seen … unless, of course, the sight of a snake is a scarifying matter for you.

Still, there are some pleasures to be had here. The Snake Woman does feature some eerie atmosphere at times, especially during its dreamlike nighttime scenes on the moors, and the film’s musical background, consisting mainly of that darn flute, by Buxton Orr (who had previously worked on ‘58’s The Haunted Strangler and Fiend Without a Face and ‘59’s First Man Into Space and Suddenly, Last Summer), goes far in creating a mood. The film’s script, by Orville H. Hampton (who’d given us ‘59’s The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake and The Atomic Submarine), is a no-nonsense and intelligent one, as far as it goes, while the cinematography by Stephen Dade (who had also worked on Doctor Blood’s Coffin, and would go on to work on the great ’64 film Zulu) is effective in creating a nice period atmosphere. As for Furie, he brings his film home as well as he might have, I suppose, being hamstrung by a small budget and his lack of an effective central monster. Furie would go on to helm such marvelous films as ‘65’s The Ipcress File, ‘72’s Lady Sings the Blues and the truly horrifying horror film The Entity (’82), and thus it is somewhat difficult to realize that he had also been responsible for this much smaller and infinitely lesser picture.

The Snake Woman is a likeable film, with its heart in the right place, but its main problem is that it just isn’t scary, or suspenseful, or even all that memorable. Travers is never given anything much to do, other than stare hard into the distance and utter a few lines in monotone; for a woman with cold blood, she fails to elicit the slightest corresponding chill in the viewer. Perhaps if theatergoers had been given ONE transformation scene, or if Atheris’ victims could have let loose with some bloodcurdling screams as they met their demise, things might have been different. But no. Compared to the Reptile creature that Jacqueline Pearce would become five years later, Atheris is very weak tea, indeed. At the tail end of The Snake Woman, the Inspector at Scotland Yard, after reading Prentice’s report, declares the affair to be “Amazing … absolutely, utterly incredible.” And indeed, such had indeed been the case. It’s just a shame that “amazing” and “incredible” don’t necessarily translate into a scary time at the movies…

1) I love how the staves in the black and white image seem to be pointing at Atheris like cartoon arrows. “Snake Woman! Here! Here!”

2) I’m glad to see the hybrid grew mammalian eyelids somewhere along the way.

3) It seems like she would be easy to contain, at least in winter, where her reptilian system would be sluggish, right?

Interesting, Marion. I don’t believe the film went into her eyelids OR her activities in the cold weather. Two more knocks against it!