![]() The Second Deluge by Garrett P. Serviss

The Second Deluge by Garrett P. Serviss

It is the Indian state of Meghalaya, just north of Bangladesh, the holds the record for being “The Wettest Spot on Earth,” getting, on average, a whopping total of 467” of rain a year. (Do bring an umbrella if you’re planning a visit!) But while this 38-foot tally, 13 times what Seattle might expect annually, is certainly impressive, it pales to insignificance compared to what descends from the heavens in Garrett P. Serviss’ 1911 novel The Second Deluge, in which, due to a cosmic mischance, no fewer than 30,000 feet of rain fall upon our fair planet in under one year … enough to effectively drown the entire world, past the tippy top of Mt. Everest itself! A wonderfully written novel that is fairly epic in scope, it is a sadly neglected apocalyptic work that is surely ripe for rediscovery in our modern-day era of climate change and rising coastal waters.

The Second Deluge was initially released as a six-part serial in the pages of The Cavalier magazine, from July – December 1911, and appeared in hardcover form the following year. It would then be reprinted in the various pulp magazines of the day (more on those in a moment) in 1926, 1933 and 1948, and later in book form again from Hyperion Press (1974), Wildside Press (2013), Gateway/Orion (2015), and the one I was fortunate enough to lay my hands on, the 2018 edition from Armchair Fiction. So yes, it has been reprinted any number of times, and should happily pose little effort to track down. As for the novel’s author, Serviss was born in upstate New York in 1851, and was thus 60 when this novel was released. A professional astronomer and journalist, Serviss was one of the most well-known popularizers of astronomy in his day, with eight books on the subject, and his knowledgeable background informs this, his fourth of five sci-fi novels, with an air of eruditeness and verisimilitude. The Second Deluge has seen all those reprints for good reason, as it turns out: It is a fairly thrilling book, generous with its sequences of cataclysmic spectacle and their aftermath, and Serviss is happily revealed to be a wonderfully talented writer. His book is actually compulsively readable; the type that one puts down with difficulty and can’t wait to pick up again. To be succinct, I loved it!

The novel introduces us to an eccentric scientist and millionaire named Cosmo Versal, who, when we first encounter him, has just ascertained a suspicion of his: The Earth, it seems, within a matter of months, would be passing through a “watery nebula,” resulting in some 30,000 feet of rain to be dumped upon the planet’s surface. Despite Cosmo’s pleas to the authorities to take action, and his presentation of mathematical proofs, he is roundly scoffed at by his fellow scientists, the newspapers, the U.S. president, and the population at large. Undeterred, Cosmo, seeing himself as a modern-day Noah of sorts, begins the construction of an 800-foot-long “ark” capable of holding 1,000 personally selected passengers, as well as a crew of 150 … and, of course, a menagerie of assorted animal and plant life. The construction of this ark, in eastern Long Island, only serves to increase the ridicule that is being heaped upon him, but when unusual meteorological events begin soon after (abnormally powerful thunderstorms, superdense fogs and drenching humidity, the melting of the glaciers and polar ice caps), the populace begins to sit up and wonder. But when the rains begin in earnest, and the crowds begin to swarm to Versal’s ark to beg for admittance, it is already too late.

During the first half of Serviss’ novel, we watch as most of the world is inundated, in scenes of marvelously well-detailed and moving destruction. But Cosmo and his fellow passengers are able to live a life not too far removed from those on a Carnival cruise vacation, sailing across the Atlantic, across the watery grave of what had once been Europe, and on to the Indian Ocean. En route, they encounter another small group of survivors in a specially made submarine, built by the French army engineer Yves de Beauxchamps, and that sub, christened the Jules Verne, proves invaluable to Cosmo’s ark in the months ahead. In the book’s second half, Versal and the ark’s skipper, the gruff and bewhiskered Captain Arms, attempt to reach the Himalayas, which Cosmo has predicted to be the area that will naturally reappear first, if and when the waters ever begin to recede. A hiatus of several weeks of clear weather, during which the Earth passes through a rift or gap in the watery nebula, gives the ark an opportunity to make some fair progress, but when our planet enters the nebula’s nucleus, and the rains begin to fall at a rate of 600 feet a day (!), the ark comes in for some very rough sledding indeed…

Now, as I have mentioned elsewhere, this reader is a big fan of the parallel-plot device, in which an author jumps from one cliff-hanger story line to another, and in The Second Deluge, Serviss supplies us with a doozy. Thus, while Cosmo Versal & Co. are busy exploring the waters covering Europe and Asia, we also get to witness the exploits of one Professor Pludder, the ex-president of the Carnegie Institution, who was one of the chief scientists urging the U.S. President Samson to ignore Cosmo’s warning … to his eternal shame and regret. As the deluge begins, Pludder (read: Plodder) hires a plane to whisk Samson and his family, as well as 20 or so others, to safety. When the plane is forced to make an emergency landing during the relentless downpour, Pludder cleverly turns the air machine into a motorized raft, with which he and his band attempt to forge their way to the hopeful promise of dry land in the Colorado Rockies. It is a fascinating alternate story line, really, and one that allows us to see how the drowned American heartland has fared.

During his novel, Serviss plies the reader with any number of memorable scenes, including the one in which Cosmo and his assistant, Joseph Smith, try to determine which 1,000 folks to bring along; the inundation of Manhattan (the destruction of the Municipal Building by an out-of-control Navy cruiser is especially well done); the drowning, dominoes-style, of the Alps and their surroundings; Samson’s chastisement of the slow-witted Pludder; a nasty mutiny aboard the ark that Cosmo and Arms are forced to contend with; a tour of the drowned Paris, as de Beauxchamps returns, via sub, to his hometown for a nostalgic visit; the disastrous tour of the inundated Egyptian pyramids and Sphinx, again aboard the Jules Verne; the ark weathering the onslaught as the nucleus is entered; the sight of de Beauxchamps standing atop the last few feet remaining of Mt. Everest, before it slips beneath the waters … the first person to ever do so (Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s ascent did not occur until 1953, it should be remembered); the scene in which Cosmo, accidentally thrown overboard, battles with a sea serpent; and a visit, via hastily constructed diving bell, to a Manhattan lying beneath six miles of water and inhabited only by various oceanic monstrosities. Wonderful sequences, all, and nicely interspersed over the course of Serviss’ lengthy story.

During his novel, Serviss plies the reader with any number of memorable scenes, including the one in which Cosmo and his assistant, Joseph Smith, try to determine which 1,000 folks to bring along; the inundation of Manhattan (the destruction of the Municipal Building by an out-of-control Navy cruiser is especially well done); the drowning, dominoes-style, of the Alps and their surroundings; Samson’s chastisement of the slow-witted Pludder; a nasty mutiny aboard the ark that Cosmo and Arms are forced to contend with; a tour of the drowned Paris, as de Beauxchamps returns, via sub, to his hometown for a nostalgic visit; the disastrous tour of the inundated Egyptian pyramids and Sphinx, again aboard the Jules Verne; the ark weathering the onslaught as the nucleus is entered; the sight of de Beauxchamps standing atop the last few feet remaining of Mt. Everest, before it slips beneath the waters … the first person to ever do so (Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s ascent did not occur until 1953, it should be remembered); the scene in which Cosmo, accidentally thrown overboard, battles with a sea serpent; and a visit, via hastily constructed diving bell, to a Manhattan lying beneath six miles of water and inhabited only by various oceanic monstrosities. Wonderful sequences, all, and nicely interspersed over the course of Serviss’ lengthy story.

The Second Deluge is set in an indeterminate future era, that could easily be either 1912 or 2012. It does contain several instances of futuristic gadgetry, such as the novel spectroscope that is an invention of Versal’s, as well as the metal called “levium” (“half as heavy as aluminum and twice as strong as steel”) with which the ark is constructed. The book contains any number of wonderfully drawn secondary characters, including the scientists whom Versal had brought aboard, but strangely enough, there is not a single female character to be seen, other than one society matron aboard the ark who wonders if Versal might search for her lost jewelry whilst taking that diving bell jaunt. But fortunately, as I mentioned, Serviss turns out to be a very solid wordsmith, with a nicely literate yet wholly engaging style. He demonstrates a knack for coming up with some apt made-up words (such as “blandiloquence” and “superphasianidaean”) and phrases (such as “ebullitions of terror”). And he only occasionally makes a misstep, such as when he tells us that Gaurisankar was the locals’ name for Everest (Gaurisankar is actually a wholly different mountain in that area), and when he gives the entire continent of South America but a single passing reference (even the destruction of Antarctica is given more attention). And then there’s that whole issue of a “watery nebula” … can such a thing possibly exist, in the absolute zero of space? Far be it from me to argue with a trained astronomer, but it does kind of stretch a reader’s credulity. Still, such is the power of Serviss’ writing that this reader was more than willing to suspend his disbelief. All told, The Second Deluge is a truly splendid novel; one that builds to a conclusion that is at once surprising, moving and satisfying.

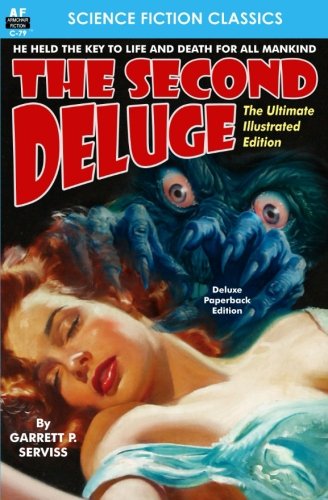

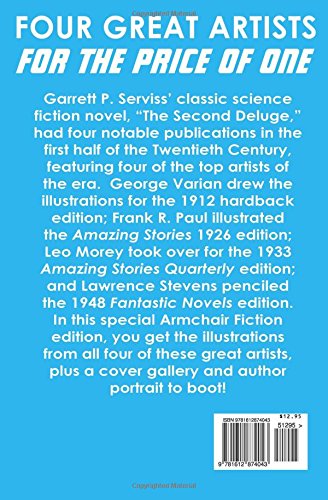

More good news for modern-day readers is the fact that this Armchair edition is a really beautiful one, mostly free of the typos that have plagued so many of the publisher’s other releases. The cover proclaims it to be “The Ultimate Illustrated Edition,” and for once the ballyhoo is well deserved, as this edition contains every illustration (both cover art and interior art) that had graced the McBride, Nast & Co. 1912 hardcover (art by George Varian), the November 1926 Amazing Stories edition (art by Frank R. Paul), the Winter 1933 Amazing Stories Quarterly edition (art by Leo Morey), and finally, the July 1948 Fantastic Novels edition (art by Lawrence Stevens). But oh … if you were wondering what the cover of this Armchair edition pertains to, depicting as it does a gorgeous, sleeping redhead being ogled by a hideous, fanged monstrosity, the answer is: Well, absolutely nothing at all! That was the cover of the July ’48 Fantastic Novels magazine, which also contained a short story called “Finis” by one Frank Lillie Pollock, and it is my suspicion that Stevens’ artwork was created for that story instead. Paul’s beautiful cover art for the 1926 Amazing, thus, would have been a much wiser choice for the fine folks at Armchair to have made. Still, it is a very winning modern edition, and at a reasonable price.

As for me, I have been made an instant fan of Garrett P. Serviss, and would certainly love an opportunity now to read his other four sci-fi novels: Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898), A Columbus of Space (1909), The Sky Pirate (also released in 1909), and The Moon Maiden (1915). I am surely going to try to track some of those titles down … while my hometown of NYC still remains standing above water…

What a cover!

Indeed! Too bad that it has nothing to do with the story….

But wasn’t that the way?