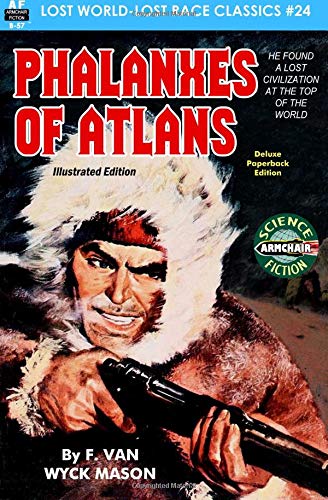

![]() Phalanxes of Atlans by F. Van Wyck Mason

Phalanxes of Atlans by F. Van Wyck Mason

A little while ago. I had some words to say about Capt. S.P. Meek’s 1930 novel The Drums of Tapajos, in which a band of American explorers discovers a lost civilization in the jungle wilderness of Brazil, comprised of the cultured and scientifically advanced remnants of the 10 Lost Tribes and Troy, uneasily coexisting with the barbaric remnants of Atlantis. The book was done in by a lack of convincing detail and exciting set pieces, as I reported. Well, now I am here to tell you of my most recent read, another offering from Armchair Fiction’s Lost World/Lost Race series; a book that suffers from one of the same problems that plague The Drums of Tapajos, even though its story line has been inverted. In this case, a pair of Americans discovers two separate lost races, uneasily coexisting in a heated valley in the Arctic, but here, the Atlanteans are the civilized ones, while the Semitic Lost Tribes are depicted as cannibalistic, idolatrous savages. The book in question is Phalanxes of Atlans, still another novel that suffers from being inadequately fleshed out, to put it mildly. More on this in a moment.

Phalanxes of Atlans was originally released in the February and March 1931 issues of Astounding Stories; that February issue was the first to feature an abbreviated name, which had been Astounding Stories of Super-Science since the magazine’s inception in January 1930. The novel’s author, Boston-born F. Van Wyck Mason, was not quite 30 when this work appeared in print, although he’d already had almost three dozen short stories appear in the pulps previously, plus two novels; his Hugh North series, which would run to seven short stories and 25 (!) novels, had begun the previous year. Mason would go on to write prodigiously in the mystery, adventure, historical fiction, and young adult fields, and this early offering of his would seem to blend all those genres into one curious stew. It is a likeable work, overall, but ultimately an unsatisfying one. It is also the first novel of Mason’s that I have read, and as was the case with Meek, I’d like to think that he improved with practice. And by the way, before I proceed: I keep referring to Phalanxes of Atlans as a novel, although there seems to be some confusion in this area. A certain Wiki site calls it a short story, which it certainly is not, while the Internet Speculative Fiction Database deems it a novel. By my rough count, this work runs to 40,000 words, and since a novella by definition contains 17,000 — 40,000 words, and a novel 40,000+, this work may fairly be classed a generously sized novella or a minimal novel. Whatever you choose to call it, however, its many attributes and deficits are glaring.

In the book, the reader encounters one Victor Nelson, who had been forced to land his plane, in the middle of a blinding snowstorm, in the wilds of the Arctic. His fellow crewman and explorer, Richard Alden, had gone to reconnoiter the immediate vicinity and had not returned, and so Nelson, when we first meet him, is trekking through the snowy wastes in search of his pal. He comes upon a tunnel of sorts at the bottom of an icy amphitheater, and entering, discovers that the tunnel is surprisingly warm, heated as it is by subterranean steam vents. While traversing the pitch-dark passage, Nelson encounters what sounds like a living animal. He shoots between its glowing eyes, only to discover, after he has gotten a match lit, that the creature is an allosaurus of the dinosaur family! Nelson is soon captured by a legion of soldiers in this tunnel and is brought, by high-speed tube, to their capital city of Heliopolis. It seems that Nelson has stumbled into the realm of the descendants of long-gone Atlantis, who have lived in their hidden Arctic valley, heated by underground steam and three enormous geysers of flame, for thousands of years. Also living peaceably with the Atlanteans are the English descendants of Henry Hudson, who had discovered the valley after being set adrift by his mutinous crew in 1611! And on the other side of the boiling Apidanus River, which divides the valley, is the benighted kingdom of Jarmuth, comprised of those previously alluded-to Semitic cannibals. And, as is so often the case in these lost-world narratives, Nelson and Alden have arrived at the worst possible moment. (“Thou hast come in stirring times,” as one of the Atlanteans remarks. “Well, we certainly picked a wonderful time to drop in on this God-forsaken country,” Alden later opines.) Thus, in the first half of Mason’s book, Nelson aids the Atlanteans in their fight against Jarmuth; in the second, he goes on a spy mission into Jarmuth itself, to rescue the Atlantean emperor’s kidnapped sister, who is about to be sacrificed to the Semites’ great god Beelzebub….

Okay, I’m going to first try to say some good things about this novel, as I always endeavor to do in all my book reviews. First, unlike the Meek book, Phalanxes of Atlans contains any number of standout scenes. Among them: that first run-in with the allosaurus; Nelson’s battle with six Jarmuthians perched atop an enormous diplodocus; Nelson and Alden being imprisoned in a jail cell, the barred door of which slowly opens, to reveal a passel of hungry allosauri outside; and Nelson’s rescue of Altara before her sacrifice, high atop a ziggurat, while Alden assists, perched on a swooping pteranodon. The superscience on display here is also kind of nifty. Thus, the Atlanteans’ high-speed tube system, run by steam; the “retortii” weapons, which employ highly condensed steam to dissolve matter; grenades that release a lethal fungus gas; and spinning discs that enable the observer to spy on distant events. Nelson himself is a hugely likeable fellow (I kept picturing Clark Gable in the role), always ready with a humorous quip, and the action in this short novel is fairly relentless. It’s as if Mason couldn’t wait to get to his huge set pieces, and thus forgot to add the convincing detail necessary to hold things together. And that’s only part of the problem.

Unresolved questions include: Who do Nelson and Alden work for? The Air Force, possibly? How did all those dinosaurs survive the journey to the heated valley all those millennia ago? How did the Atlanteans and Semites get there to begin with? How do the Semites manage to cross the boiling waters of the Apidanus? Why do the Lost Tribes write in Sanskrit? Why do the Atlanteans and Hudsonians incorporate so many Roman, Grecian and Egyptian references in their place names? And finally, after a culmination that is way too abrupt, what happens to our heroes at the end? Nelson and Altara marry, but do they remain in the hidden valley? Ultimately, the reader comes away from Phalanxes of Atlans with the distinct impression that this should have been a three-part serial, as was The Drums of Tapajos, instead of a two-parter. Given another 75 pages to expand his conceit and present his story with a more leisurely exposition, Mason might have really had something here. As things are, this is something of a fun and fast-moving hodgepodge of a mess.

And there are other problems, too. The treatment of the barbaric Lost Tribes strikes the modern-day reader as being more than subtly anti-Semitic (“A bunch of the boys from Seventh Avenue,” as Nelson refers to them); Mason occasionally gets his historic facts wrong (he tells us that the dinosaurs died out 5 million years ago; that should be more like 65 million years ago!); and many of the casual references (such as the 20th Century Limited, Germans being referred to as “the Boche,” 10-20-30 melodramas, the Ziegfeld Follies, the Armenian refugees, the Moth plane, the once-popular song “He Ain’t Done Right By Nell”) strike the modern ear as being hopelessly dated. But since this story is supposed to take place in the year 1931, one must make allowances for these necessarily dated bits. The bottom line, as you can tell, is that Phalanxes of Atlans is something of a mixed bag, at best. Mason is quite evidently a better writer than Meek, sentence for sentence, but in this work, at least, a dearth of explanatory detail merely leaves us with a string of action scenes, and that, unfortunately, is just not enough to make for a compelling experience. What my main man, H. Rider Haggard, the “Father of the Lost World Novel,” seemingly did so easily (except in his 1909 novel The Yellow God, which also suffers from a lack of convincing detail) was to prove a great challenge for so many of his imitators. Without a clearly thought-out background for its story, mere action, unfortunately, is never enough.

But wait … this Armchair edition is not quite finished! To round out the volume, we have one additional tale, William P. McGivern’s “The People of the Pyramids,” which originally appeared in the December ’41 issue of Fantastic Adventures magazine. Chicago-born McGivern was another remarkably prolific author; although he ultimately came out with around 20 novels, roughly one-quarter of Mason’s output, he also wrote over 100 sci-fi short stories. Indeed, “The People of the Pyramids” was originally published as by “P. F. Costello,” because McGivern had another story, “Rewbarb’s Remarkable Radio,” in that selfsame issue! In this tale, a novelette of roughly 15,000 words, an American named Neal Kirby finds himself involved with a mysterious blonde and a sinister Austrian man while browsing in a curio shop in Cairo. He agrees to help pretty Jane Manners in her search for the lost desert city that her archeologist father had discovered some years before. And ultimately, that lost city is indeed found by Kirby, but only after Jane is abducted by the Austrian and Kirby is left to die in the middle of the blazing desert. A chance gunshot at a descending vulture impinges on a force field of sorts, revealing a previously invisible pyramid (only one pyramid; the title of the story is a misnomer). Upon awakening from a swoon, Kirby learns that he is 500 feet underground, among the residents of this lost city … a city of advanced scientific attainments, which the Austrian hopes to exploit for his own gain…

Anyway, this is a very well-written, fast-moving and exciting little tale, with several well-done scenes (Kirby’s solo desert trek is especially well depicted), but — yet again — an inadequate amount of detail. Thus, the reader is again left with many questions unanswered, such as: Who is Neal Kirby, and what was he doing in Cairo? We learn absolutely nothing of his background, other than the fact that he is an American with a good right hook. What is the name of that lost city? What is the history of its people? What is the purpose of that enormous, screened pyramid, if all the residents seem to abide underground? How are Kirby and Jane going to return to Cairo at the end? Ultimately, what we have here, in essence, feels like a treatment for a future novel; some good ideas put on paper that needed fleshing out so as to make for a convincing read. Still, taken together with Phalanxes of Atlans, I suppose that what we have here is a well-paired double feature of sorts from Armchair Fiction. And, oh … as for this volume itself, added points for photographs of both authors and the inclusion of the magazines’ original cover and interior artwork; points off for Armchair’s typically sloppy typographical presentation. A word of advice to the editors there: Come on, guys! Hire a good proofreader already!!!

No, Paul, sorry, I don't believe I've read any books by Aickman; perhaps the odd story. I'm generally not a…

I like the ambiguities when the story leading up to them has inserted various dreadful possibilities in the back of…

COMMENT Marion, I expect that my half-hearted praise here (at best) will not exactly endear me to all of Ramsey…

Ramsay Campbell was all the rage in my circle of horror-reading/writing friends in the 1980s, and they extolled the ambiguity.…

Oh boy, I wish I could escape that Neil Gaiman article, too. I knew already he’d done reprehensible things but…