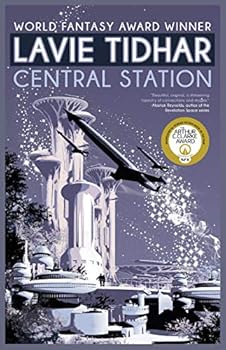

![]() Central Station by Lavie Tidhar

Central Station by Lavie Tidhar

Central Station is a thoughtful, poignant, human take on a possible future. For the most part Central Station occurs at the titular port on planet earth. This space resides in what we know today as Tel Aviv, but in the distant future it has gone through many names and many people. Everything seems to begin in earnest when Boris Chong arrives in Central Station after spending a great deal of time away — some of which on Mars. Central Station, the place, is a half-thought meeting of a variety of worlds. Central Station the book is more thoughtful than I think I know how to express, but I’ll give it a try.

Central Station occurs in the very spot where humans expanded from our first planet throughout the solar system. Humans, robotniks, children who live and breathe the virtuality known as The Conversation, and the Others all coexist at the hub of the known universe. Lines between humanity and technology blur as advances continue and people are ‘noded’ into The Conversation at birth. In the chaos of so many people and ideas together at once Central Station explores a richness of culture that doesn’t even exist yet. The depth to which this book seems to go is no less than breathtaking. How beings interact, their customs and beliefs, their superstitions and mysteries — Central Station provides a world in which plurality is the norm and nothing is normal. Lavie Tidhar has created a world here that is heart-achingly our own and at the same time bewilderingly other.

Central Station spends the vast majority of its time following a cast of characters as unique, broken, strange, and complex as anyone who has ever existed. I say it often, but for me characters are absolutely essential to good reading. Central Station has deep characters in spades. Tidhar has expertly navigated the space between presenting the reader with characters to empathize with and providing ample reason to want to always continue reading their lives.

Central Station may have space travel and cyborg technology at its disposal, but this is not a story about alien tech or technological marvels. Central Station, to me, is very much a moment in time. Central Station gives the feeling that at any second there are over 7 billion people alive right now, and it is just focussing on a few. It looks at the life Boris has lead as he tries to reconcile with his family’s curse. It looks at Marion as both a young lover and an indomitable business owner. It looks at what it means to be an outcast from a few distinct angles. It lays bare the prejudices held and values lost by a future that has robotniks to fight its wars. I could go on but I think I can’t say it all better than this book does.

Central Station is about humanity in every form it may take. It’s about yearning and hopes and frustrations. Its intricate design of life, love, and happenstance in a distant future isn’t so much grounded in a forced humanity as revelling in it. It’s also about mysteries never to be solved. There are a fair few things in Central Station that I continue to wonder about. In most stories without a foreseeable continuation these kinds of loose ends would bother me. In the case of Central Station they lend to the idea that what I read was just a moment. There was time in the lives of the characters before the story began, and there is life after. Central Station is written like a segment of history, except that it’s set in the future.

If you’re looking for a plot-heavy sci-fi narrative you may want to look elsewhere. If you’re looking for a deeply complex comment on humanity in a future where many lines are blurred, this is the right pick for you.

~Skye Walker

![]() I’m a sucker for linked story collections. Sure, at their worst they can feel like a lazy person’s cheap novel — a thrown together bunch of old stories with a few perfunctory transitions/connections. But at their best they mix the concentrated focus and power of a short story with the weight and depth of a longer narrative arc, making for a wonderfully discursive, elliptical, and yet strong-hitting creation. And that’s exactly what we have in Lavie Tidhar’s Central Station, a beautifully constructed and composed linked-story novel/collection.

I’m a sucker for linked story collections. Sure, at their worst they can feel like a lazy person’s cheap novel — a thrown together bunch of old stories with a few perfunctory transitions/connections. But at their best they mix the concentrated focus and power of a short story with the weight and depth of a longer narrative arc, making for a wonderfully discursive, elliptical, and yet strong-hitting creation. And that’s exactly what we have in Lavie Tidhar’s Central Station, a beautifully constructed and composed linked-story novel/collection.

I come first to Central Station on a day in winter. African refugees sat on the green, expressionless. They were waiting, but for what, I didn’t know. Outside a butchery, two Filipino children played at being airplanes: arms spread wide they zoomed and circled, firing from imaginary underwing machine guns. Behind the butcher’s counter, a Filipino man was hitting a ribcage with his cleaver, separating meat and bones into individual chops. A little farther from it stood the Rosh Ha’ir shawarma stand, twice blown up by suicide bombers in the past but open for business as usual. The smell of lamb fat and cumin wafted across the noisy street and made me hungry.

Here in the opening paragraph you can already see some of Central Station’s strengths, beginning with the vivid, precise details. The imaginary airplanes aren’t just “shooting bullets” but firing from “underwing machine guns.” The butcher isn’t just hitting a clump of meat, but a “ribcage.” The food stand isn’t just a stand but a shawarma stand, and it doesn’t smell simply of “exotic spices” but “lamb fat and cumin.” This level of care to detail runs throughout the book making this world come wholly alive.

Another aspect shown in the opening paragraph is the rich soup that is the world of Central Station, which as the book goes on will turn out to be populated by the aforementioned Africans, Filipinos, shawarma lovers, orthodox Jews, cyborgs, robotniks, visitors from Mars, data vampires, genetic engineers, disembodied artificial intelligences (“Others”), mysterious lab-created children, and more. And these are just the characters. Throw in the science fiction trappings that seem to appear a dozen to a page (only a slight exaggeration) and you have a wonderful panoply of creativity on display — exodus ships, AIs, immersion pods, bioweapons, robot soldiers, wearables, solar buses, and behind it all, the Conversation:

Everything was noded. Humans, yes, but also plants robots, appliances, walls, solar panels, nearly everything was connected… across that region called the Middle East, across Earth, across trans-solar space and beyond… a human was surrounded, every living moment, by the constant hum of other humans, other minds, an endless conversation.

The idea of the Conversation, of connection, is nicely mirrored by Central Station’s structure of linked stories and by the way in which Tidhar weaves the connecting threads amongst them via characters, words, and images. In a nice bit of layering, he as well works in genre allusions, such as a reference to the “nine billion names of God” or “Elronism.” The metafictional aspects appear as well in direct references to lives as stories, as when one character realizes that “life wasn’t like that neat classification system… Life was half-completed plots abandoned, heroes dying halfway along their quests…” And later, the narrator tells us, “It is perhaps the prerogative of every man or woman to imagine, and thus force a shape, a meaning onto that wild and meandering narrative of their lives, by choosing genre.”

The imaginative richness, sharpness of detail, and complexity of connections would make this a good book, but it’s the depth of characterization and amount of feeling in their stories that makes it an excellent one. Stories of love and loss and regret and relationships and fathers and sons and mothers and sons and old friends and new friends and once-old-friends-not-new-again. Central Station is a lyrically told, expertly constructed tale that moves even as it impresses in its craftsmanship. Highly recommended.

~Bill Capossere

![]() Central Station is a brilliantly imagined, vividly detailed world, where Lavie Tidhar stitches together concepts about scientific developments, the future of humanity, community and family, love, religion and individual choice, all at the same time. It’s an impressive and beautiful patchwork quilt; it’s just that there isn’t a whole lot of plot to it. Central Station is more focused on the ideas and the characters. But what scintillating ideas, and what fascinating characters!

Central Station is a brilliantly imagined, vividly detailed world, where Lavie Tidhar stitches together concepts about scientific developments, the future of humanity, community and family, love, religion and individual choice, all at the same time. It’s an impressive and beautiful patchwork quilt; it’s just that there isn’t a whole lot of plot to it. Central Station is more focused on the ideas and the characters. But what scintillating ideas, and what fascinating characters!

The novel is set in and around Central Station, an immense space port located in Tel Aviv, where a quarter million refugees and migrants live in clustered around the base of the space station. Most people have a genetically built-in data node that connects them virtually to the world around them, making them permanently part of the “Conversation,” the online communication. It’s all internet, all the time. Some people are genetically engineered in labs that can remove genetic diseases along with giving you patented and trademarked features like “green Bose” or “Armani blue” eyes. Between the Others ― purely digital entities and personalities ― exist all types of mixes: cyborg-like robotniks, vampirish Strigoi who hunger for data and memories from their victims, and more. Those who are human are a mix of cultures and nationalities: Jewish, Chinese, Russian and many more. It’s a true melting pot.

Like a futuristic Cannery Row, Central Station follows episodes in the lives of various characters who live around Central Station space port, touching and changing each other’s lives. We begin with Boris Chong, who returns to Earth after many years working in space. His version of the built-in data node is a biological networking augmentation, a pulsating biomass permanently attached behind his ear. He runs into his former lover Miriam, who is raising Kranki, a boy even more connected to the Conversation than most, who even has a virtual friend. These characters connect in turn to others, all different types of humans, part-humans and Others, but all, at heart, worthy of sympathy and consideration as people.

A nice touch of humor is added by a chatty elevator and other smart appliances with artificial intelligence:

A group of disgruntled house appliances watched the sermon in the virtuality — coffee makers, cooling units, a couple of toilets — appliances, more than anyone else, needed the robots’ guidance, yet they were often willful, bitter, prone to petty arguments, both with their owners and with themselves.

I think my favorite creation was Carmel, the data vampire, inflicted with the Nosferatu Virus, driven to suck data from the necks of humans who have the ubiquitous data node. Like the Shambleau of old, she is feared and hunted down by humans, but the digital Others have a particular role in mind for her.

Tidhar’s rich, allusive writing contains a wealth of ideas and a breathtaking vision for what humanity may become. In the vast differences between the various types of characters, it becomes clear that it’s the similarities that are most important, connecting people in all our diversity. While I would have like a more fully developed plot, in the end I felt like I had gained in insight and compassion by being immersed in the day-to-day world of the people of Central Station.

~Tadiana Jones

This looks like one I have to read!